Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6437

Research Article Volume 14 Issue 5

1Department of Anesthesiology, Center for Plastic Surgery, Mexico

2Department of Nursing, Department of Anesthesiology, Center for Plastic Surgery, Mexico

Correspondence: Luis E Carreto, Department of Anesthesiology, Center for Plastic Surgery, Ingenieros Civiles 9989.Décima Sección CP 22020 Tijuana Baja California Mexico

Received: September 25, 2022 | Published: October 3, 2022

Citation: Carreto LE, Rangel EG, Montes K. Relation between preoperative fasting time and the plestimographic variability index (PVI). J Anesth Crit Care Open Access. 2022;14(5):165‒167. DOI: 10.15406/jaccoa.2022.14.00531

Preoperative fasting can also lead to physiological deleterious effects such as dehydration, and hypovolemia. The Plethysmographic Variability Index (PVI, Masimo Corp, Irvine, CA, USA), is a dynamic measurement and its variability could be related to hydration status.

Objective: Find a correlation between the number of hours of preoperative fasting and the measurements of PVI.

Studio and design: Experimental, prospective, longitudinal.

Material and methods: During one-year, patients ASA I scheduled for elective general anesthesia, in an outpatient plastic surgery clinic, the nurse staff recorded PVI (%) values by MightySat® Masimo finger oximeter pulse and the hours of fasting carried out the night before their admission by direct interrogation of the patient. a simple linear regression with Pearson correlation coefficient, perfect = 1, to find a relation between fasting hours and PVI, being considered significant with a p< 0.05.

Results: 140 patients were included, women (90%), mean age 35 years, the mean PVI values were 21.01 (SD +/- 7.20) means hours of preoperative fasting performed by patients 11.85 (SD+/- 2.34). Pearson correlation coefficient between fasting hours and PVI was 0.005 (t-student 0.0054, p bilateral 0.47)

Conclusion: This study did not show a linear relation, direct or inverse, between fasting hours and PVI values. PVI as a dynamic measurement of preload or stroke volume did not show changes in terms of fasting time in our patients.

Keywords: Index of plestimographic variability (PVI) and preoperative fasting

The evaluation of adequate parenteral hydration is of vital importance for the maintenance of cardiac output and thus avoid situations of hypovolemia is tissue hypoxia. Technological advances have allowed the use of continuous measurements and dynamic indices, in real time and non-invasive, with potential applications in the management of HP. Such is the case of the Plethysmographic Variability Index (PVI, Masimo Corp, Irvine, CA, USA), which analyzes the degree of variability of the plethysmographic curve in relation to respiratory cycles.1 This variability could be related to hydration status of the patient under general anesthesia and on mechanical respiratory support. The PVI is calculated based on the Infusion Index (PI). The PI is a relative assessment of the pulse pressure at the recording site, its calculation is based on the fact that the arterial blood flow is pulsatile (AC) in some tissues such as the fingers while in others the flow is not, that is, it is continuous (DC). The pulsation of arterial blood modulates the degree of absorption of light that passes through, while the other fluids and tissues do not, thus maintaining a constant absorption. The PI is defined as the ratio between CA and DC expressed as a percentage, with values ranging from very low perfusion (0.4%) to high perfusion (20%), estimated at the measurement site.

In a series of publications, Cannesson et al.2,3 studied PVI and volume expansion, differentiating responders from non-responders to fluid administration. When the PVI is greater than 14%, patients respond to volume expansion, while when the PVI is less than 14%, patients do not respond to fluid administration. The MightySat®finger pulse oximeter obtains the extraction of PI and PVI signal under the Rainbow SET (Signal Extraction Technology) platform, designed by the Masimo Company (Masimo Corp, Irvine, CA, USA) In addition to the oxygen saturation (SpO2) and heart rate (FC) recording performed by conventional oximeters, this platform can record total hemoglobin (SpHb®), carboxyhemoglobin (SpCO®), methemoglobin (SpMet®).4

The use of PI and PVI monitoring have inversely correlated with systolic (SAD), diastolic (TAD) and mean TAM blood pressure monitoring. Tsuchya et al, using logistic regression analysis, found a correlation between PVI values greater than 15 and decrease in TAM, concluding that the PVI might be able to identify those patients susceptible to developing arterial hypotension during anesthetic induction.5

Preoperative fasting has been a requirement for those patients undergoing elective general anesthesia, considered fundamental for initial perioperative protection in a patient. However, it is widely recognized that preoperative fasting can also lead to physiological deleterious effects such as dehydration, hypovolemia, plasma volume and interstitial fluid volume are decreased proportionally during overnight.6 We hypothesize that PVI measurements could correlate with preoperative fasting hours in patients scheduled to receive general anesthesia at a plastic surgery clinic. And deduce that fasting promotes a state of hypovolemia that can respond to intravenous (IV) fluids determined by PVI values.

Objective

Find a correlation between the number of hours of preoperative fasting and the measurements of PVI.

Studio and design

Experimental, prospective, longitudinal.

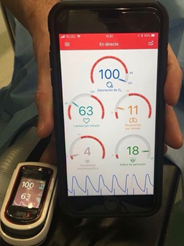

During one-year patients scheduled for elective general anesthesia, in an outpatient plastic surgery clinic, with prior consent for non-invasive monitoring by patients, and before administration of parenteral liquids, the nurse staff recorded demographic data such as age, gender, weight, height, heart rate, respiratory rate, non-invasive arterial pressure and PVI (%) and PI values by means of MightySat® Masimo finger oximeter pulse (Figure 1). The PVI and PI measurements were made according to the specifications of the device instruction manual. In the same way, the hours of fasting carried out the night before their admission were obtained by direct interrogation of the patient. For those patients, who would receive anesthesia 2 hours after admission, they were not administered clear liquids orally according to preoperative fasting guidelines7 until they had the measurement of PVI and PI.

Figure 1 MightySat® Masimo. Oximeter with the different measurement parameters (PVI and PI) displayed on a mobile device through the Masimo app.

ASA I patients scheduled for elective general anesthesia, with hours of preoperative fasting (8 minimum).

Patients ASA II or more, patients with the intake of some consumption of medication or vitamins, 24 hours before the onset of anesthesia.

Those patients in whom a satisfactory measurement of PVI and PI could not be obtained, or incomplete information of the demographic data.

Statistical analysis

It was performed by the estimation of mean and standard deviation for numerical variables that follow a normal distribution and frequencies for qualitative variables. As well as a simple linear regression with Pearson correlation coefficient, perfect = 1, to find a relation between fasting hours and PVI, being considered significant with a p< 0.05. The SPSS version 24 program was used for Windows 2017.

A total of 140 patients were included, 126 women (90%) and 14 men (10%), mean age 35 years, mean TAM was 84 (SD+/- 11.24), mean heart rate 74 (SD+/-14.54), the mean PVI values were 21.01 (SD +/- 7.20) of PI of 4.75 (SD +/- 13.84), mean hours of preoperative fasting performed by patients 11.85 (SD+/- 2.34). Pearson correlation coefficient between fasting hours and PVI was 0.005 (t-student 0.0054, p bilateral 0.47), (Graphic 1&2), while the correlation of fasting hours and PI was -0.008 (t student 0.094, p bilateral 0.46).

So far we do not know any study or reference that establishes any relationship or independence between the hours of preoperative fasting and the values of the PVI plesthymographic variability index. This study considered preoperative measurements of PVI using MightySat® Masimo. Oximeter in patients scheduled to receive general anesthesia for plastic surgery procedures.

Traditionally, preoperative fasting is believed to cause hypovolemia in patients presenting for surgery. Fluid losses during fasting occur primarily by urinary output and evaporation from the skin and airway. These losses decrease fluid in the extracellular space, of which the intravascular space is a relevant component.

This study did not show a linear relation, direct or inverse, between fasting hours and PVI values. There are conflicting data as to whether fasting has a significant effect on blood volume, and whether that affect is as significant as once was thought. Toshihiro et al. found that preoperative dehydration after overnight fasting per se does not provide a rationale for intravascular volume loading with crystalloid solution, at least in low risk patients.6,8 Jacob et al. studied 53 patients using direct blood volume measurements with tracers and did not find a change in blood volume from the calculated normal values in patients who had an extended overnight fasting period.9,10 Muller et al. did a prospective study on American Society of Anesthesiologists class I to III patients presenting for elective abdominal or gynecologic surgery without bowel preparation and a >8-hour preoperative fast. Transthoracic echocardiography was performed and did not show significant changes in stroke volume or respiratory variations of the IVC with fasting both at rest and in response to a passive leg raise test.11

PVI as a dynamic measurement of preload or stroke volume did not show changes in terms of fasting time in our patients, many of them performed more than 8 hours of fasting by their own decision, and even so there was no direct or inverse relation. The results coincide with other dynamic measurements made in studies such as those of Muller et al or Jacob.9-12 The importance of the study establishes to avoid aggressive pre-emtive intravenous fluid resuscitation before of general anesthesia based on the belief of hypovolemia in patients with preoperative fasting, or who will respond to fluids for certain PVI and PI values, however, there was not such significant relation. Perhaps more studies are necessary, with a greater number of patients, and with a category different from ASA I to be able to find a significant direct or inverse linear relationship between the preoperative fasting time and PVI and PI. So also with a more objective control than the direct interrogation about the hours of fasting by the patients, since our study, being outpatients, they get into clinic the day of surgery, performing the preoperative fast of 8 or even more hours.

None.

©2022 Carreto, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.