Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6437

Research Article Volume 12 Issue 2

1SBU Umraniye Training and Research Hospital Clinic of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Umraniye, Turkey

2SBU Umraniye Training and Research Hospital Clinic of Nephrology Umraniye, Turkey

Correspondence: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ahmet AKYOL, SBU Umraniye Training and Research Hospital Clinic of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Elmalikent Mah., Adem Yavuz Cad. No: 1 (34764) Umraniye, Istanbul, Turkey, Tel +90 533 6331369

Received: April 24, 2020 | Published: April 28, 2020

Citation: Akyol A, Sit D, Kayabasi H, et al. Is pantoprazole associated with proteinuria in intensive care patients? J Anesth Crit Care Open Access. 2020;12(2):74-77. DOI: 10.15406/jaccoa.2020.12.00435

Purpose: Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are widely used in intensive care units (ICU). Adverse events such as acute interstitial nephritis, acute kidney injury and progression in chronic kidney disease have been frequently reported due to the use of PPIs. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effects of pantoprazole, a PPI derivative, on renal functions.

Materials and methods: The study was conducted by retrospectively analyzing the data of 60 patients aged 24-89, who were admitted to the ICU, examined and treated. The patients participated in the study were divided into two groups as Group A (n=36; pantoprazole group) and Group B (n=24; control group). The study included patients who had normal renal function tests when admitted to the ICU, who were not in the risk group for kidney diseases, whose complete urinalysis, spot urine protein/creatinine ratio (PCr) and serum creatinine levels were studied during admission to and discharge from the unit, and who were hospitalized in the ICU for at least 48 hours. The urine output, spot urine protein/creatinine ratios (PCr), serum creatinine level (sCr), estimated glomerular filtration rate of the patients were evaluated at admission and discharge from the ICU.

Results: The study was conducted with 60.0% participation of Group A and 40.0% participation of Group B. The mean age of the patients was 59.18±17.77 years, the length of ICU stay was 6.75±10.81 days, and there was no significant difference between the intra-group urine outlet values; however, the amount of urine output was significantly higher in the control group and there was a statistically significant difference (p<0.001). There was no statistically significant difference between urine PCr values by groups both at intensive care admission and discharge (p=0.35, p=0.421). Compared to the control group, the increase in discharge spot urine PCr of the pantoprazole group was statistically significantly higher than the admission spot urine PCr (p=0.594, p=0.048). There was no statistically significant difference in all parameters of sCR within and between the groups (p>0.05).

Conclusion: PPIs are not completely free of adverse effects, as noted by some practitioners. As demonstrated in the present study, the use of pantoprazole may be associated with isolated proteinuria. Therefore, the renal profile of patients should be closely monitored to prevent undesired renal complications.

Keywords: pantoprazole, proteinuria, kidney functions, intensive care unit

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are commonly prescribed for different medical reasons. These drugs, which can sometimes be used for months and years, are frequently used for short periods of time.1 In intensive care units (ICU), almost all patients are initiated on PPIs to manage acid-related pathologies and to minimize the role of various treatments, including surgical treatments, due to their strong acid suppressive effects.2,3

Although PPIs have an excellent overall safety profile, several drawbacks have been raised recently due to its negative effects on renal functions, especially their relationship with acute interstitial nephritis (AIN). Renal adverse effects of PPIs are relatively infrequent, but the widespread use of these drugs may cause these adverse effects to be seen frequently.1,4 Renal injury induced by PPIs is generally asymptomatic and does not exhibit systemic allergic symptoms; the median time from the onset of the drug to the diagnosis of the picture, which slowly progresses to renal failure, usually exceeds a few months. Renal toxicity associated with the use of PPIs and complications that may have negative effects on the patient's morbidity and mortality, such as isolated hematuria and/or albuminuria/proteinuria, acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease may develop with the occurrence of acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) mainly due to a class effect.5-7 There is a limited number of data investigating the renal complications developing in this patient population initiated on PPIs.

Clinicians consider PPIs as safe agents, especially in the ICU; however, we think that this view should be reconsidered in the light of the latest evidence. For this purpose, we wanted to evaluate the renal adverse effect profile of PPIs and especially its effects on proteinuria in patients who were admitted, followed up and treated in the ICU of our hospital.

The study was conducted by retrospectively analyzing the data of a total of 60 patients between the ages of 24-89 who were hospitalized in University of Health Sciences, Umraniye Training and Research Hospital, Anesthesiology and Reanimation Clinic, Intensive Care Unit between January 1, 2019 and December 31, 2019. The patients participated in the study were divided into two groups as Group A (n=36; administered pantoprazole as PPI) and Group B (n=24; control group - no drug used). The study included patients who had no known kidney disease, had normal renal function tests when admitted to the ICU, whose complete urinalysis, protein/creatinine ratio (PCr) and serum creatinine levels were studied during admission to and discharge from the unit, and who were hospitalized in the ICU for at least 48 hours. As kidney function tests, urine output, spot urine protein/creatinine ratios (PCr), serum creatinine level (sCr), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) were evaluated both during admission to and discharge from the ICU. The diagnosis of acute kidney injury was evaluated according to the 2012 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) diagnostic criteria8 and eGFR was calculated according to the CKD-EPI equation.9 Those with pathology on renal imaging (renal ultrasonography, computed tomography, etc.) were not included in the study. Those with known chronic kidney disease or with evidence of chronic kidney disease in imaging methods, diabetic, hypertensive patients, obese individuals (Body mass index >28 kg/m2), those followed up with the diagnosis of sepsis and systemic infection, those with a history of heart failure, and those who had a hypotensive episode while being followed up in the ICU were excluded from the study.

Statistical analyses

NCSS (Number Cruncher Statistical System) 2007 (Kaysville, Utah, USA) software was used for the statistical analyses. Descriptive statistical methods (mean, standard deviation, median, frequency, percentage, minimum, maximum) were used to evaluate the study data. The normality distribution of quantitative data was tested by the Shapiro-Wilk test and graphical evaluations. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare two groups of non-normally distributed variables. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the measurements of non-normally distributed variables at admission and discharge.

The level of significance was accepted as p<0.05.

The study was conducted on a total of 60 patients, with 60.0% (n=36) participation of group A (pantoprazole group) and 40.0% (n=24) participation of group B (control group). There was no statistically significant difference between Group A patients, 47.22% (n=17) of whom were female and 52.78% (n=19) of whom were male, and Group B patients, 41.67% (n=10) of whom were female and 58.33% (n=14) of whom were male, in terms of gender (p>0.05). The ages of the patients ranged between 24 and 89 years, with a mean age of 59.18±17.77 (median 59.5) years, and the length of ICU stay was 2-60 (6.75±10.81) days. There was no statistically significant difference between age and length of ICU stay by groups (p=0.581 and p=0.387, respectively) (Table 1).

|

Parameters |

Group A (n=36) |

Group B (n=24) |

Total (n=60) |

ap |

|

Age (years) |

58.53±17.20 |

60.86±19.74 |

59.18±17.77 |

0.581 |

|

Gender (F/M) Duration of ICU (day) |

17/19 7.24±11.70 |

10/14 5.45±8.35 |

27 / 33 6.75±10.81 |

(-) 0.387 |

|

SBP (mmHg) |

121.38±10.15 |

118.42±13.21 |

120.92±11.57 |

0.543 |

|

DBP (mmHg) |

79.25±7.48 |

74.50±8.73 |

76.38±8.14 |

0.302 |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

26.72±10.02 |

25.71±8.32 |

26.12±7.85 |

0.416 |

|

Urine output (mL/day) |

1297.9±2276.9 |

1810.0±191.83 |

1502.54±1442.87 |

0.0001 |

Table 1 Comparison of general characteristics of patients by groups

aMannWhitney U Test, ICU; Intensive Care unit, SBP; Systolic Blood Pressure, DBP; Diastolic Blood Pressure, BMI; Body Mass Index

The indications for admission to the ICU are given in Table 2.

|

Hospitalization Indication |

Group A |

Group B |

|

Postoperative |

26 |

18 |

|

Respiratory Failure (COPD, pneumonia, ARDS, etc.) |

5 |

3 |

|

Intoxication (drug, CO, etc.) |

2 |

1 |

|

Accident (traffic, work, etc.) |

3 |

2 |

Table 2 Indications for admission to the intensive care unit by groups

There was a statistically significant difference the mean urine amounts by groups (p<0.001), the urine output was significantly higher in the control group. However, there was no statistical difference between both groups in terms of intra group admission and discharge parameters (1297.9±2276.9 ml/day and 1810.0±191.83 ml/day; p>0.05) (Table 1).

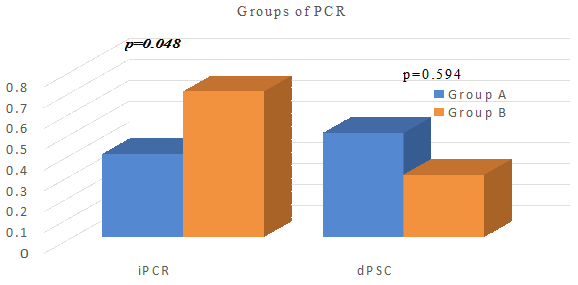

In all patients, there was no statistically significant difference between both admission and discharge spot urine PCr values by groups (p=0.35, p=0.421; p>0.05). Compared to the control group (Group B), the increase in discharge spot urine PCr of the PPI group (Group A) was statistically significantly higher than the admission spot urine PCr (p=0.594, p=0.048; p<0.05, respectively) (Table 3, Figure 1).There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in terms of changes in the discharge urine PCr compared to the admission values (p=0.161; p>0.05).

|

Group A (n=36) |

Group B (n=24) ap |

|||

|

Urine PCR (Admission) |

Min-Max (Median)

Mean±SD |

0.2-1.5 (0.4) 0.59±0.41 |

0.1-4.2 (0.7) 1.51±1.63 |

0.355 |

|

Urine PCR (Discharge) |

Min-Max (Median)

Mean±SD |

0.2-5.2 (0.5) 1.10±1.29 |

0-5.6 (0.3) 1.31±1.86 |

0.421 |

|

bp 0.048* |

0.594 |

|||

|

Creatinine (Admission) |

Min-Max (Median)

Mean±SD |

0.4-2.8 (0.8) 0.93±0.46 |

0.5-2.4 (0.7) 0.96±0.50 |

0.903 |

|

Creatinine (Discharge) |

Min-Max (Median)

Mean±SD |

0.5-1.4 (0.7) 0.80±0.28 |

0.5-2.9 (0.7) 1.10±0.80 |

0.755 |

|

bp 0.268 |

0.515 |

|||

Table 3 Changes in spot urine protein/creatinine ratio and serum creatinine levels by groups

aMannWhitney U Test bWilcoxonSignedRanks Test

Figure 1 Evaluation of spot urine protein/creatinine ratios between groups.

iPCr; protein creatinine rate at admission, dPCr; protein creatinine rate at discharge.

When evaluated in terms of serum creatinine, there was no statistically significant difference in all parameters within and between the groups (p=0.903, p=0.755, p=0.268, p=0.515; p>0.05, respectively) (Table 3).

A drug such as PPIs or histamine-2 receptor antagonist or sucralfate is used as a standard treatment in almost every patient hospitalized in intensive care units to prevent gastric acid secretion and to avoid side effects such as stress ulcers.4 PPI-induced renal side effects are thought to be a common class effect. This effect is triggered by immune hypersensitivity reaction to the drug or one of its metabolites. Ruffenach et al. published the first case report of AIN due to omeprazole in 1992.10 Further community-based studies11 have identified a higher risk of AIN and AKI in patients using PPIs, and the medium and long-term evidence has shown that these patients who had AIN and/or AKI have low eGFR in their long-term follow-ups and patients using PPIs have a higher risk of CKD.4-6

A meta-analysis by Nochaiwong et al. including about 2.6 million patients in observational studies and case series, 534.003 (20.2%) of whom were PPI users, found a significantly increased AKI [RR 1.44 (% 95 CI 1.08-1.91); p = 0.013] and AIN risk [RR 3.61 (% 95 CI 2.37-5.51); p<0.001], as well as an association with an increased risk of chronic kidney disease [RR 1.36 (% 95 Cl 1.07-1.72); p=0.012] and end-stage renal failure (ESRD) [RR 1.42 (% 95 Cl 1.28-1.58); p0.001] compared to non-PPI users.6

About 80% of pantoprazole is metabolized in the kidneys and is retained in the plasma for 10-12 hours.12 After acute interstitial nephritis caused by this drug was first reported in 2004,13 and there were a limited number of reports including pantoprazole-related kidney complications, most of which were obtained from case reports.13-16 In an experimental study, pantoprazole has been shown to alleviate renal injury following renal ischemia/reperfusion, and this effect may be partly due to the inhibition of oxidative stress and the TLR-4 signal pathway.17 However, kidney problems such as pantoprazole-related acute interstitial nephritis and acute kidney injury are considered as increasingly common and more known complications of PPIs treatment.5,6

There was no finding suggestive of acute kidney injury and acute interstitial nephritis in the pantoprazole group and the control group included in our study throughout the follow-up period. There was no change in serum creatinine, urine output values that would meet the AKI criteria of the KDIGO guidelines. There was no statistically significant difference within and between both groups in terms of ICU admission and discharge values of sCr. Although urine output was within normal limits in both groups, the amount of urine was significantly higher in the control group than in the pantoprazole group (p<0.0001).

In our patient population, there was a statistically significant difference between the ICU admission and discharge PCR values of the pantoprazole group compared to the control group without any significant statistical difference between the two groups (p=0.048). Interestingly, the hemodynamic parameters of these patients were stable and had no clinical and laboratory data to suggest AIN and/or AKI. Reports on proteinuria in pantoprazole-induced kidney injury are rare, and protein has not been detected in the urine of patients in most studies, including case reports.18,19 This result, despite the limitations of our study, suggests that the use of pantoprazole may be associated with isolated proteinuria.

The limitations of our study are the prospective design of the study, short follow-up duration and absence of no standard follow-up duration, conducting the study in a specific patient population such as ICU patients, relatively small number of participants, and inadequate homogeneity of the participating groups.

In conclusion, PPIs are not completely free of adverse renal effects, as assumed by many clinicians. Our study suggests that the use of pantoprazole may be associated with isolated proteinuria without causing drug-related pathologies such as acute interstitial nephritis, acute kidney injury in the ICU patients using pantoprazole in our study cohort. However, these study results should be checked and validated with large-scale studies.

Not applicable.

None of the authors has any financial or personal relationship with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence or bias the results.

The data sets analyzed in the present study can be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

AA, DS, HK, designed the study and drafted the manuscript. AA, MZU, GK, and EYE collected the clinical and laboratory data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

©2020 Akyol, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.