Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6437

Case Report Volume 14 Issue 5

1Pediatric Department Mother and Child University Hospital of the Canary Islands, Spain

2Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, Mother and Child University Hospital of the Canary Islands, Spain

3Department of Clinical Sciences, Fernando Pessoa Canarias University, Spain

Correspondence: José Manuel López Alvarez, Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, Mother and Child University Hospital of the Canary Islands, Spain

Received: September 30, 2022 | Published: October 31, 2022

Citation: Arango IB, Pardo RDB, Alvarez JML. Autoinflammatory syndrome in an infant with suspected sepsis. J Anesth Crit Care Open Access. 2022;14(5):174‒177. DOI: 10.15406/jaccoa.2022.14.00533

Introduction: Autoinflammatory diseases encompass a group of rare pathologies characterized by acute and recurrent inflammatory episodes. Their clinical manifestations are very diverse and can affect practically any organ. The confirmatory diagnosis is based on genetic study but must be performed and interpreted correctly. Treatment with biologic drugs that block proinflammatory cytokines has been shown to be effective in a large proportion of patients.

Case summary: 39-day-old infant admitted to intensive care with fever, skin lesions and marked irritability associated with acute respiratory failure and haemodynamic instability. On admission, he presented with a marked leukocytosis with neutrophilia and elevated inflammatory parameters without improvement despite antibiotic, antiviral and antifungal treatment. A thorough microbiological study was completed and no cause was found. After ruling out infectious, haematological and neoplastic causes, autoinflammatory disease was suspected. Finally, a genetic study revealed a pathogenic variant in the RIPK1 gene, and the patient was diagnosed with CRIA syndrome.

Conclusion: Autoinflammatory diseases are unusual pathologies that should be suspected in cases of systemic inflammation in which autoimmune, neoplastic and infectious disorders are ruled out. Their diagnosis is complex due to clinical similarity and lack of specific criteria. Further studies on patients with RIPK1 gene alterations are needed to know in more detail their clinical features, response to treatment and prognosis.

Keywords: Autoinflammatory diseases, Interleukin-1beta, macrophage activation syndrome, RIPK1, CRIA

Autoinflammatory diseases are a group of rare pathologies characterized by recurrent systemic inflammatory crisis in the absence of infectious, autoimmune or neoplastic etiology. These disorders are mediated by a continuous overproduction and release of proinflammatory mediators, specially interleukin-1-beta.1 All of them share an alteration of innate immunity leading to an inflammatory system dysfunction, including inflammasome disorders without infectious, neoplastic or autoimmune cause.2 The most common diseases are familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), TNF receptor-associated syndrome (TRAPS), mevalonate kinase deficiency/hyper-IgD syndrome (MKD/HIDS) and cryopyrin-associated autoinflammatory syndromes (CAPS).3

Signs and symptoms are very diverse. It frequently includes fever, rash, serosal injuries and increased acute phase reactants, but a wide variability of clinical features such as vasculopathies, enteropathies and neurological alterations should be taken into account. The age of onset is variable, although most debut in pediatric age.4 Diagnosis is mainly clinical and based on phenotypic features. Genetic confirmation is of vital importance, as they are hereditary diseases caused by mutations in genes coding for proteins directly involved in inflammation and its regulation.5 Treatment will depend primarily on the type of disease and the response to the chosen therapy. Proinflammatory cytokine blocking therapy, particularly IL-1 blockers, has shown to be effective in many patients with autoinflammatory disorders.6

Since their definition in 1999, the number of inherited autoinflammatory diseases has been slowly increasing, due to a better understanding of the conditions and mainly to advances in genetic diagnosis.7 Autoinflammatory diseases are rare pathologies in which definitive diagnosis is hard to reach.8 This is due to the absence of diagnostic criteria for each disease, the clinical similarity between them, the existing limitations in performing genetic studies and the lack of specific laboratory markers. Despite the fact that these are hereditary disorders, family history is rare.9 Therefore, diagnosis can be delayed and lead to the appearance of complications due to the course of the disease. However, infectious, immune and neoplastic causes should be ruled out before autoinflammatory syndrome is suspected.7

A 39-day-old female patient with no relevant perinatal history came to the emergency department with fever up to 37.8ºC and an irritability period of 24 hours. On evaluation she presented a good general condition and an unremarkable physical examination. Complementary tests showed Hb 9.3 gr/dl, leukocytes 21,700, neutrophils 58.2%, lymphocytes 25%, C-reactive protein (CRP) 1.71 mg/dl and leukocyturia. The patient was admitted for febrile urinary tract infection due to ampicillin-sensitive Escherichia coli with normal renal ultrasound, initially treated with ampicillin and gentamicin. After 48 hours of admission, the patient showed vesicular-pustular lesions with erythematous base starting in the periumbilical region with subsequent generalization (Figure 1), as well as bilateral conjunctival exudate, liquid stools and rhinorrhea, persisting with high fever peaks and remarkable irritability, so antibiotherapy was rotated to cefotaxime and gentamicin, and treatment with acyclovir was added. Lumbar puncture was performed without significant findings. After 24 hours the patient remained febrile and showed clinical worsening with acute respiratory failure and signs suggestive of sepsis, so he was admitted to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU).

On admission to the PICU, he presented respiratory gasping and hemodynamic instability, requiring orotracheal intubation and support with invasive mechanical ventilation. She also required continuous noradrenaline perfusion due to sustained arterial hypotension, which could be withdrawn without further complications 48 hours after admission to the PICU.

At the time of admission, the patient presented a striking leukocytosis up to 45,600/uL with a remarkable left shift (neutrophilia 35,300/uL), with increased acute phase reactants (CRP up to 33.7 mg/dL, ferritin 1,024 ng/mL, D-dimer 18,164 ng/mL) and initially a moderate thrombocytosis that progressed a few days later to thrombocytopenia of 55,000/uL. Due to the poor evolution, antibiotic therapy was again changed to linezolid, meropenem and azithromycin. Antiviral treatment was continued and fluconazole was added due to thrombocytopenia and to the presence of fresh yeast in urine sample, which was later ruled out in culture.

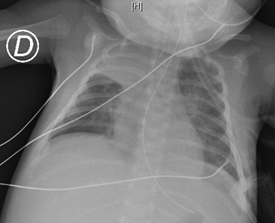

A detailed infectious study was completed, which showed negative microbiological findings (blood culture, control urine culture, cerebrospinal fluid culture, stool culture, conjunctival exudate culture, nasopharyngeal culture, bronchial aspirate culture), with negative serology (syphilis, HIV, EBV, CMV, Herpes simplex 1 and 2, VZV). Imaging tests (chest X-ray (Figure 2), abdominal, transfontanellar, thoracic and cervical ultrasound) revealed no pathological findings.

Figure 2 Increased density with retraction of the right upper lobe fissure in association with atelectasis.

A skin biopsy of the lesions showed a combination of inflammatory patterns with neutrophilic infiltration of the dermis with some immature forms of histiocytoid type, neutrophilic spongiosis and vacuolar damage, with positive immunohistochemical profile for imnunoperoxidase, CD15, CD68. It is oriented as a neutrophilic dermatosis. After these results and after ruling out hematologic, infectious, and neoplastic causes, autoinflammatory disease was suspected. Due to this suspicion, treatment was started with anakinra (IL1-blocker) and megadoses of methylprednisolone for 3 days, followed by maintenance oral corticosteroid. Subsequently, she presented a strikingly good response, with clinical and analytical stability. The patient was transferred to the hospital conventional ward and after a few days discharged home. Prior to discharge, a sample was taken for genetic study.

She was readmitted at 3 months of age due to reactivation of the disease (high fever, skin lesions, vomiting) in the context of a decrease in corticotherapy, which was resolved with an increase in the dose of anakinra and corticoids. Finally, a pathogenic variant in the RIPK1 gene was found in the genetic study, being diagnosed with CRIA syndrome.

In 2019, two independent groups,10,11 describe a new early onset autoinflammatory disorder caused by mutations in the gene encoding RIPK1, an important regulator of apoptosis, necroptosis and innate immune signaling pathways. Mutations in RIPK1 prevent caspase 8 from cleaving the mutated protein, which promotes RIPK1 activation and drives an autoinflammatory response.11 Individuals affected by this pathology suffer from periodic fevers, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, arthralgias and anemia. Most of them respond to IL-6 inhibition with tocilizumab.12 They named this new pathology as cleavage-resistant RIPK1-induced autoinflammatory syndrome (CRIA). 10 In our case the symptoms were much more severe than those described in the literature, requiring intensive care support. The severity of the clinical presentation leads us to think that a macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) could have been associated, complicating the management of the debut of the disease. MAS is a potentially lethal complication that can be secondary to autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases, caused by uncontrolled activation of the immune system and which can lead to multiorgan failure.13 Clinically it is characterized by high and persistent fever, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly and central nervous system injuries, and can lead to cardiac, renal and pulmonary failure. The main analytical alterations include leukopenia, anemia and thrombocytopenia, hypertransaminasemia and moderate hypoalbuminemia, as well as coagulopathy with hypofibrinogenemia and increased D-dimer. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is usually not very elevated, as well as the CRP increases dramatically and its elevation correlates with severity. The high elevation of ferritin is one of the most typical parameters of SAM, frequently reaching over 10,000 ng/mL in the acute phase.14 Our patient presented similar characteristics to SAM, but we were unable to rule out this pathology, which is why treatment with anakinra was finally initiated. Anakinra is an immunomodulatory drug that antagonizes the interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor, and has been shown to be effective in the treatment of SAM.15,16

As previously mentioned, within the autoinflammatory diseases it is challenging to define the definitive diagnosis based on clinical features as they all present heterogeneous manifestations that may overlap with each other.9 One of the first diagnostic suspicions was CINCA/NOMID syndrome (chronic, infantile, neurological, cutaneous articular syndrome/neonatal onset multi-inflammatory disease), due to the age of presentation (neonate/infant) and the clinical presentation based on fever, anemia, skin lesions, irritability and elevated acute phase reactants. CINCA/NOMID syndrome is one of the most expressive and severe autoinflammatory syndromes included within the cryopyrinopathies, an essential protein in the control of interleukin-1β production and encoded by the CIAS15 gene. One of the main characteristics of this pathology is arthropathy, not present in our patient.17 Another possible diagnosis was APLAID syndrome (auto-inflammation and phospholipase Cγ2 (PLCγ2)-associated antibody deficiency and immune dysregulation) based on the generalized vesiculo-pustular lesions present in our patient, which are very common of this disease18 (Table 1). Finally, it is the genetic study that confirms with accuracy the CRIA syndrome suffered by our patient, but it must always be performed and interpreted correctly.7

|

Category |

Age of Onset |

Genetics |

Signs and symptoms |

Treatment |

Severity |

NOMID |

Cryopyrinopathies |

Neonatal-onset |

AD inheritance |

Urticaria |

IL-1 antagonists |

Moderate/severe |

FCAS |

Cryopyrinopathies |

Neonatal-onset |

AD inheritance |

Cold-induced urticaria |

Avoid cold |

Mild |

HIDS |

Periodic fever |

< 1 year old |

AR inheritance |

Aphthas |

Systemic corticosteroids |

Good prognosis |

DIRA |

Pyogenic disorders |

Neonatal-onset |

AR inheritance |

Pustular psoriasis |

IL-1 antagonists |

Moderate |

PLAID |

Miscellaneous mechanisms |

Neonatal-onset |

AD inheritance PLCG2 gen |

Cold-induced urticaria |

High doses of systemic corticosteroids |

Moderate |

JIAs |

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis subtype |

Childhood, frequent < 1 year old

|

Unknown |

Arthritis |

High-dose systemic corticosteroids |

Moderate |

Table 1 Differential diagnosis of autoinflammatory diseases

AD; autosomal dominant, AR; autosomal recessive, NOMID; Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease, FCAS; Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome, HIDS; hyperimmunoglobulin D Syndrome, DIRA; Deficiency of IL-1 Receptor Antagonist, PLAID; PLCG2 associated antibody deficiency and immune dysregulation, JIAs; systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIAs)

Autoinflammatory diseases are unusual pathologies that should be suspected in cases of systemic inflammation in which autoimmune, neoplastic and infectious disorders are ruled out. Since their description more than 20 years ago, autoinflammatory diseases have been growing exponentially thanks to advances in the knowledge of the pathophysiological pathways involved in autoinflammation, accepting that dysregulation of innate immunity is the main mechanism involved. Nevertheless, it is now believed that there is a "continuum model" between autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases that do not necessarily have to be opposed.

However, diagnosis remains challenging due to the overlapping of symptoms and the absence of specific criteria, which is why the genetic study is of crucial importance. However, this should be interpreted with caution due to the existence of mutations without clinical significance that may be confusing. The recent discovery of RIPK1 deficiency and CRIA has improved the understanding of the molecular mechanisms of RIPK1 function in humans but many questions remain to be answered. In addition, further studies on patients with alterations in the RIPK1 gene are needed to understand in more detail their clinical features, response to treatment and prognosis.

This clinical case is published with the informed consent of the mother.

None.

None.

©2022 Arango, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.