Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6437

Research Article Volume 7 Issue 5

Department of Anesthesiology, Nippon Medical School, Japan

Correspondence: Yuko Furuichi, Department of Anesthesiology, Nippon Medical School, 1-1-5, Sendagi, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan 113-8603, Tel (+81)03-3822-2131, Fax (+81)03-5685-3077

Received: April 02, 2017 | Published: April 5, 2017

Citation: Furuichi Y, Sakamoto A (2017) An Under-Body Blanket is More Effective than an Over-Body Blanket in Reducing Intraoperative Hypothermia in Patients Undergoing Robot-Assisted Laparoscopic Prostatectomy: A Retrospective Study. J Anesth Crit Care Open Access 7(5): 00277. DOI: 10.15406/jaccoa.2017.07.00277

Purpose: The study aimed to investigate whether an under-body blanket is more effective than an over-body blanket in preventing intraoperative hypothermia in patients undergoing robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALP).

Methods: This was a retrospective observational study. We analyzed the medical records of patients who underwent RALP between January 2014 and December 2015 at Nippon Medical School Hospital. The patients were divided into the following groups: under-body blanket group (n=89) and over-body blanket group (n=43).

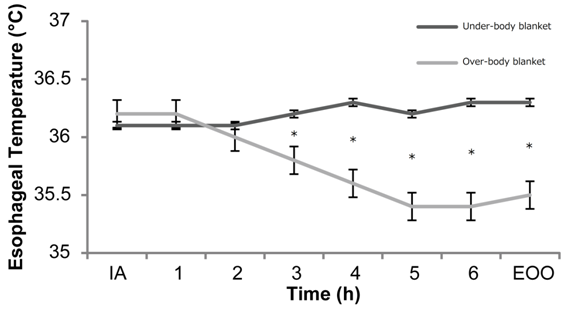

Results: The number of patients using the under-body blanket and the over-body blanket was 89 and 43, respectively. Intraoperative temperatures (at 3 h, 4 h, 5 h, and 6 h after induction of anesthesia, and at the end of the operation) and the postoperative temperature (on arrival in the ward and at 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, and 4 h after arrival in the ward) were significantly higher in the under-body than the over-body blanket group. The maximum and minimum temperatures of the patients and the serum creatinine levels were significantly higher in the under-body blanket group than in the over-body blanket group just after the operation, on postoperative day 1, and just before discharge. The postoperative course was not significantly different between the two groups.

Conclusion: The under-body blanket was observed to be more effective in preventing intraoperative hypothermia in patients undergoing RALP than the over-body blanket.

Keywords: under-body blanket, robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy, forced-air warming system, hypothermia

Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALP) is becoming a major surgical approach. This technique has been reported to lead to an improved quality of life and oncological outcomes.1 The first RALP in our hospital was performed in January 2014. Prevention of intraoperative hypothermia is important in RALP, similar to other operations. Intraoperative hypothermia is associated with greater intraoperative bleeding and blood transfusion.2,3 prolonged recovery from anesthetics and muscle relaxants.4,5 higher rate of major morbidity (cardiac, respiratory, infectious).5-7 and prolonged hospital stay.3,6 Maintenance of normothermia is one of the important elements in the guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection and enhanced recovery and surgery (ERAS) protocol.8,9

To prevent intraoperative hypothermia, we initially used an infusion fluid warmer and a forced-air warming system along with an over-body blanket. However, the over-body blanket interfered with the operative field, and an under-body blanket was introduced in October 2014. The objective of this study was to investigate whether an under-body blanket is more effective than an over-body blanket for preventing intraoperative hypothermia in patients undergoing RALP.

This study was a retrospective observational study and it was approved by the ethics committee of Nippon Medical School Hospital (No. 27-02-555). Eligible subjects were patients who underwent a scheduled RALP between January 2014 and December 2015 at Nippon Medical School Hospital. Patients were excluded from the study if the type of warming blanket used during surgery was not documented in their records. We divided the patients into two groups: patients who used an under-body blanket and those who used an over-body blanket. Their medical records were then analyzed.

An epidural catheter was inserted before the induction of anesthesia unless the patient had coagulopathy or a history of use of anticoagulant or antiplatelet drugs. The patients were anesthetized using propofol (1 -2 mg/kg body weight), rocuronium (0.6 -1 mg/kg body weight), fentanyl (0 -200 μg), and remifentanil (0 -0.2 μg/kg/min). Tracheal intubation was performed. After inserting a nasogastric tube and radial artery, venous, and urinary catheter, temperature probe was placed in esophagus. Anesthesia was maintained using sevoflurane (1.5 -2% inspired concentration) and remifentanil (0 -0.2 μg/kg/min). The dose of anesthesia was determined by the anesthesiologist in charge.

After induction of anesthesia, patients were warmed with an under-body or over-body blanket connected to forced air heaters (Bair Hugger®; 3M company, St Paul, MN, USA) at 38 °C. The temperature and humidity of the operating room were set at 28°C and 40-43%. At the end of the operation, if patient was too hypothermic (<35 °C), we usually warmed the patient under anesthesia. After the patient’s temperature had recovered to 35 °C or higher, we stopped anesthesia and removed the tracheal tube (warming before extubation) after recovery of consciousness. The esophageal temperature was measured intraoperatively, and the axillary temperature was measured postoperatively. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM, Version 21.0). The Mann-Whitney test was performed, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 142 patients underwent RALP between January 2014 and December 2015. Ten patients were excluded from the study because the type of warming blanket was unknown. The number of patients using an under-body blanket was 89 and the number of patients using an over-body blanket was 43. Preoperative characteristics of the patients are listed in Table 1. The under-body blanket group was older and the over-body blanket group had a lower prevalence of diabetes mellitus. Intraoperative management is shown in Table 2. Water balance and urine output were larger in the over-body blanket group. Warming before extubation was more frequent in the over-body blanket group. Compared with the over-body blanket group, the intraoperative temperature was significantly higher in the under-body blanket group at 3 h (36.2 ± 0.6 vs. 35.8 ± 0.6 °C), 4 h (36.3 ± 0.7 vs. 35.6 ± 0.7 °C), 5 h (36.2 ± 0.7 vs. 35.4 ± 0.8 °C), and 6 h after induction of anesthesia (36.3 ± 0.6 vs. 35.4 ± 0.8 °C). It was also higher in the under-body blanket group than the over-body blanket group at the end of the operation (36.3 ± 0.7 vs. 35.5 ± 0.7 °C). The maximum (36.6 ± 0.6 vs. 36.3 ± 0.5 °C) and minimum (35.8 ± 0.5 vs. 35.3 ± 0.8 °C) temperature were higher in the under-body blanket group than in the over-body blanket group (Figure 1).

|

Under-Body Blanket |

Over-Body Blanket |

P |

|

|

Age (years) |

67.7±5.3 |

65.2±6.4 |

<0.05 |

|

Body weight (kg) |

65.6±9.0 |

67.3±10.2 |

NS |

|

Body height (cm) |

165.7±5.3 |

167.1±5.8 |

NS |

|

Cardiovascular disease |

7 |

6 |

NS |

|

Spirometer abnormality |

23 |

16 |

NS |

|

Cerebrovascular disease |

5 |

2 |

NS |

|

Hypertension |

43 |

16 |

NS |

|

Diabetes mellitus |

9 |

11 |

<0.05 |

|

Dyslipidemia |

16 |

10 |

NS |

|

Anti-platelet drugs or |

15 |

8 |

NS |

|

Anti-coagulation drugs |

|||

|

Smoking |

45 |

20 |

NS |

Table 1 Preoperative characteristics of the two groups

|

Under-Body Blanket |

Over-Body Blanket |

P |

|

|

Use of epidural catheter |

80 |

40 |

NS |

|

OP time (min) |

273±60 |

272±55 |

NS |

|

Fluid balance (mL) |

3192±1073 |

3434±671 |

0.055 |

|

Bleeding (mL) |

197±232 |

258±217 |

NS |

|

Urine output (mL) |

215±310 |

320±316 |

<0.005 |

|

Autologous blood donation (mL) |

426±196 |

460±270 |

NS |

|

Interval between end of the OP and EX (min) |

14.6±6.9 |

19.2±13.4 |

0.092 |

|

Interval between end of the OP and leaving OR (min) |

44.1±14.5 |

47.2±14.6 |

NS |

|

Warming before arousal |

0 |

5 |

Table 2 Intraoperative managements of the two groups

OP: Operation; EX: Extubation; OR: Operating Room.

Figure 1 Changes in the intraoperative body temperature in the under-body blanket group and over-body blanket group with time. IA: induction of anesthesia.

EOO: End of Operation, * <0.05.

The postoperative temperature was significantly higher in the under-body blanket group than the over-body blanket group on arrival in the ward (36.8 ± 0.6 vs. 36.5 ± 0.8 °C). It was also higher at 1 h (37.5 ± 0.8 vs. 36.9 ± 0.6 °C), 2 h (37.7 ± 0.7 vs. 37.1 ± 0.6 °C), 3 h (37.8 ± 0.4 vs. 37.4 ± 0.6 °C) and 4 h (37.9 ± 0.4 vs. 37.4 ± 0.5 °C) (Figure 2) after arriving in the ward. On laboratory examination, serum creatinine level was significantly higher in the under-body blanket group just after the operation, on postoperative day 1, and just before discharge (Table 3). The postoperative course was not significantly different between the two groups (Table 4).

Figure 2 Changes in the postoperative body temperature in the under-body blanket group and over-body blanket group with time.

POD1: Postoperative Day 1; *<0.05.

|

Under-Body Blanket |

Over-Body Blanket |

P |

|

|

Hemoglobin (g/dL) |

|||

|

Preoperative |

14.5±1.3 |

14.2±1.2 |

NS |

|

Right after OP |

13.0±1.4 |

13.0±1.0 |

NS |

|

POD1 |

13.0±1.3 |

12.8±1.1 |

NS |

|

Platelet count (103/μL) |

|||

|

Preoperative |

20.9±4.6 |

21.7±5.5 |

NS |

|

Right after OP |

18.2±4.0 |

18.5±4.3 |

NS |

|

POD1 |

17.9±4.0 |

17.6±4.1 |

NS |

|

Creatinine (mg/dL) |

|||

|

Preoperative |

0.89±0.20 |

0.83±0.15 |

NS |

|

Right after OP |

1.09±0.25 |

0.93±0.19 |

<0.0001 |

|

POD1 |

1.32±0.76 |

0.74±0.03 |

<0.05 |

|

Before discharge |

0.90±0.25 |

0.81±0.18 |

<0.05 |

Table 3 Laboratory data of the two groups

OP: Operation; POD: Post Operative Day.

|

Under-Body Blanket |

Over-Body Blanket |

P |

|

|

Shivering |

15 |

13 |

0.064 |

|

Bleeding |

0 |

0 |

- |

|

Cardiovascular complication |

1 |

0 |

NS |

|

Wound infection |

0 |

0 |

- |

|

Hospital stay (days) |

10.7±3.0 |

10.7±3.1 |

NS |

|

In-hospital death |

0 |

0 |

- |

|

Perioperative death |

0 |

0 |

- |

Table 4 Postoperative course of the two groups

In this study, intraoperative temperature was significantly higher with an under-body blanket, and the higher temperature continued from 3 h after induction of anesthesia until 4 h after the operation. Warming before extubation was more frequent in the over-body group, so the under-body blanket has the potential to contribute to efficient management of the environment of the operation room. The effectiveness of the blanket was dependent on the gross area that it could transmit warm air to the patient’s body. Therefore, for RALP surgery patients, the under-body blanket may be a better option than the over-body blanket, because the former could cover more body area of the patient. The core body typically decreases during the first hour under general anesthesia, even in patients who receive forced air warming.10 However, our study indicated that the temperature of patients in both groups does not decrease during the first hour under general anesthesia. It is possible that a lag time existed between anesthesia induction and the insertion of the esophageal temperature probe.

Intraoperative bleeding and postoperative hemoglobin and platelet levels were similar between the two groups. RALP basically causes a small amount of bleeding, so the two groups may not a noticeable difference in bleeding. The Postoperative course was similar in both groups. RALP is basically a minimally invasive operation, and a difference may not be seen between the two groups. The postoperative creatinine level was significantly higher in the under-body blanket group than the over-body blanket group. Intraoperative water balance and urine output were larger in the over-body blanket group, so the over-body group might have received more hydration, and postoperative creatinine was low. Recently, mild hypothermia was reported to protect renal function.11 and postoperative hyperthermia is related to postoperative acute kidney injury.12 There is a possibility that intraoperative and postoperative hypothermia in the over-body blanket group was protective for renal function.

Various methods have been developed to prevent and treat intraoperative hypothermia. Forced-air warming systems actively prevent intraoperative hypothermia and numerous studies have been performed to examine their efficacy and safety.13,14 This system sends warmed air through the warming device to the container, which is usually a two-layered blanket in direct contact with the patient’s skin. The warmed air escapes through the micro-pores of the blanket, and convection flow between the blanket and the patient warms the patient’s body uniformly, and decreases heat dissipation. There are various types of blankets tailored to different needs. The under-body type blanket is comparatively new, can warm the entire body of the patient uniformly from the patient’s back, and does not interfere with the operating field even in wide-field operations such as cardiac surgery, esophageal carcinoma surgery, head and neck carcinoma surgery with laparotomy, and RALP. The under-body blanket does not place local pressure on the patient’s skin and it has a smaller risk of decubitus ulcer and low-temperature burns compared with a water mattress.

The efficacy of the under-body blanket has not yet been established. This is the first report that investigated the efficacy of the under-body blanket in RALP. RALP is a wide-field operation and it requires a particular body position and placement of the robot close by, so it is often difficult to prevent hypothermia using an over-body blanket. Idei et al reported that the forced-air warming system using an under-body blanket was effective in preventing intraoperative hypothermia and promoting extubation in the operating room during endovascular aneurysm repair.15 Emmert et al.16 reported that warming with an under-body blanket prevents perioperative hypothermia during video-assisted thoracic surgery.16

There are several study limitations. First, this was a retrospective observational study. Second, the number of cases was too small. Finally, the intraoperative anesthetic management was up to the discretion of the anesthesiologist in charge.

An under-body blanket is more effective than an over-body blanket in preventing intraoperative hypothermia in patients undergoing RALP.

There are no conflicts of interest in this study.

Author declares there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2017 Furuichi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.