Journal of

eISSN: 2373-6437

Case Report Volume 2 Issue 2

1Director Division of Cardiac Anesthesia, Associate Professor of Anesthesiology, State University of New York, USA

2Assistant Professor of Pharmacy Practice, St. John Fisher College, Wegmans School of Pharmacy, USA

3Good Samaritan Hospital, USA

Correspondence: Muhammad F Sarwar, Director Division of Cardiac Anesthesia, Associate Professor of Anesthesiology, State University of New York, 750 East Adams Street Syracuse, New York 13210, USA, Tel 315-750-0681

Received: February 09, 2015 | Published: April 2, 2015

Citation: Sarwar MF, Sarwar NA, Vent D (2015) Aggressive Anesthetic Management of a Patient with Severely Dilated Cardiomyopathy for Non Cardiac Surgery. J Anesth Crit Care Open Access 2(2): 00049. DOI: 10.15406/jaccoa.2015.02.00049

We report a case of a 37 year old man, with history of rhabdomyosarcoma as a child. Patient developed severe dilated cardiomyopathy secondary to the treatment of the cancer. He presented for resection of the small bowel. An intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) was placed preoperatively for mechanical cardiac support. A combined general/epidural technique was used for the surgery. Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) was used to monitor patients cardiac status intraoperatively. Patient remained hemodynamically stable and tolerated the procedure well.

Keywords: Dilated cardiomyopathy, Intra aortic balloon pump, Epidural, Hemodynamics, Noncardiac surgery, Chemotherapy induced cardiomyopathy, Chemotherapy, TEE, Transesophageal echo, Intraoperative echo, Aggressive management

IABP, Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump; TEE, Transesophageal Echocardiogram; LV, Dilated Left Ventricular; MR, Mitral Regurgitation

A case of a patient with severe dilated cardiomyopathy, undergoing small bowel resection. Anesthesia was managed with a combination of general/epidural anesthesia, in addition to IABP and TEE.

A 37 year old white male presented to our surgical department for small bowel resection. Patient’s history was significant for rhabdomyosarcoma, diagnosed at the age of five. The rhabdomyosarcoma was treated, but recurred four years later. Patient’s treatment regimen included Adriamycin. On this presentation, patient’s medical history was significant for malignancy in the ileostomy that was a result of radiation enteritis. In addition, as a result of the treatment regimen, patient has developed severe non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Preoperative transthoracic echocardiogram was significant for severely dilated left ventricular (LV) cavity, LV ejection fraction of <10% and severe mitral regurgitation (MR).

On the day of surgery, a left radial arterial line was placed for close and accurate monitoring of hemodynamics. Unsuccessful attempts were made to cannulate both the internal jugular and the left subclavian veins. All three sites had been cannulated multiple times over the years. Patient had an indwelling catheter in the right subclavian. An epidural catheter was placed, both for intraoperative use and post operative pain control. General anesthesia was induced, intravenously, through an 18 gauge angiocath in the right upper extremity. After a smooth induction of anesthesia, the trachea was intubated and the position of the endotracheal tube confirmed.

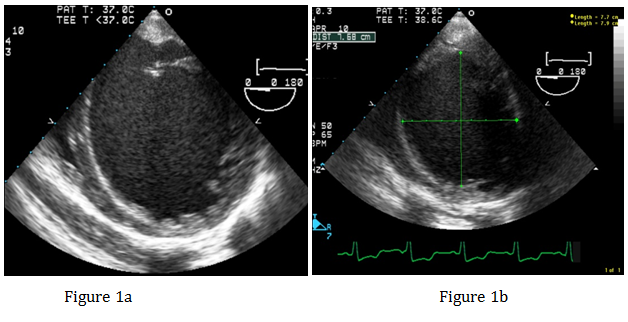

After emptying the stomach, the TEE probe was placed without difficulty. IABP was placed via the right femoral artery. Position of the IABP was confirmed with the TEE. Operation of the IABP was confirmed. A left femoral venous cordis was placed and central access was established. Preoperative TEE found an LV ejection fraction of approximately 5%, severely dilated LV (Figure 1a & Figure 1b), moderately dilated right ventricle, and moderate to severe right ventricular hypokinesis. Patient had a 4+ MR, with significant reversal of the systolic component of the right superior pulmonary venous profile (Figures 1c & Figure 1d).

Figure 1a&1b Transgarstric Short Axis view of the left ventricle showing severely dilated left ventricle.

Figure 1d Pulsed wave Doppler of the right superior pulmonary vein demonstrating reversal of the systolic component of the pulmonary venous profile. Consistent with the severe MR.

During the surgery, anesthesia was maintained with narcotics, inhalational agent and the epidural. Patient remained hemodynamically stable during the procedure. No significant changes were noted on the TEE during the surgery. IABP functioned adequately, providing mechanical support.

Although our patient did not undergo an endocardial biopsy to confirm the etiology of his cardiomyopathy, Adriamycin cannot be ruled out as an etiological factor. Adriamycin is a chemotherapeutic agent, which belongs to the Anthracycline group of drugs. Anthracyclines are one of the most potent anti-cancer drugs developed to date.1 Adriamycin is considered a first line treatment of several cancers.2 Adriamycin is an antibiotic obtained from cultivating Streptomyces peucetius var. caesius.3

Cardiac toxicity of Adriamycin is well known. It is the cause of significant mortality and morbidity. Manifestation of Adriamycin cardiotoxicity can range from arrhythmias to nonspecific ECG changes to a reduction in LV ejection fraction.1 Endomyocardial biopsy remains the definitive test for diagnosing anthracycline-induced toxicity.4 Risk factors for developing irreversible anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity include high dose infusions, high cumulative doses, extremes of age (like our patient) and history of cardiac disease. History of previous mediastinal radiation therapy and the concurrent use of chemotherapeutic agents like paclitaxel or trastuzumab can contribute to anthracycline cardiotoxicity.5-8 Incidence of cardiotoxicity ranges from 0.4 to 41%.1 In the acute form, cardiomyopathy manifests as myocarditis-pericarditis, usually within 24 hours of the infusion, with good long term prognosis. In it’s subacute form, it may manifest as late as 30 months after adriamycin therapy, with 60% mortality. Late form cardiomyopathy may not be seen until four to 20 years later. This form is associated with echocardiographic and pathologic changes, in addition to heart failure.9

Severity of cardiac dysfunction in our patient warranted aggressive anesthetic management. Although there are reports of using TEE in patients with severely dilated cardiomyopathy,10,11 it was of paramount importance for our case, since we were unable to place a pulmonary artery catheter preoperatively for adequate hemodynamic monitoring. As it was critical not to overload this patient with fluids, TEE helped with monitoring the volume status. In our literature search, we did not come across any other case of severely dilated cardiomyopathy in which IABP was utilized to provide mechanical cardiac support. In our case, the afterload reduction, provided by the IABP, played a big role in the hemodynamic stability of this patient during the surgery. Placement of the epidural catheter, made it possible for us to limit our use of general anesthetics and avoid unnecessary depression of myocardial function.

At the conclusion of the surgery, patient was adequately reversed and extubated on the operating table. Patient was awake, alert, breathing spontaneously and pain free. Since the patient still had an IABP in place, he was transported to the cardiac intensive care unit for further postoperative care. Patient’s postoperative course remained uneventful.

None.

None.

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2015 Sarwar, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.