Journal of

eISSN: 2572-8466

Research Article Volume 7 Issue 3

1Department of Geography / Environmental Management, Nigerian Defence Academy (NDA), Nigeria

2Department of Biological Science, Nigerian Defence Academy, Nigeria

Correspondence: Ayodele A Otaiku, Department of Geography / Environmental Management, Doctoral student, Nigerian Defence Academy (NDA), Faculty of Arts & Social Science, , Kaduna, Nigeria, Tel +234 803 3721219

Received: December 09, 2019 | Published: June 30, 2020

Citation: Otaiku AA, Alhaji AI. Characterization of microbial species in the biodegradation of explosives, military shooting range, Kaduna, Nigeria. J Appl Biotechnol Bioeng 2020;7(3):128-147. DOI: 10.15406/jabb.2020.07.00226

Kachia military firing range since 1965 in situ characterization of microbes present in explosives contaminated soils was investigated. Bacteria gram stain morphological and biochemical characterization of the different microbial isolates. Bacterial DNA extracted from soil samples was achieved using the 16SrRNA is amplified using Polymerase Chain Reaction with the following microbes (Lysini bacillus, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter spp, Bacillus subtilis, Klebsiella pneumomia, Achromobacter spp and Arcobacter spp) was confirmed and results compared with the sequence obtained from the nucleotide database of National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Fungal species isolates are: Rhizopus spp, Aspergillus niger, Penicillium spp, Trametes versicolourand Phanorochate chrysoporium may adapted to metabolise the explosives and heavy metals contaminant xenobiotic by biodegradation. Percentage isolates occurrence: 75% Enterobacterspp (highest) and 33% Escherichia coli (lowest); 67% Aspergillus niger (highest); and 17% for Penicillium sppand Trametes versicolor (lowest) respectively. Microbial biodegradation of explosives is considered to be most favourable under co-metabolic conditions. Site study explosives treatment by bioremediation will requires bioaugmentation of isolated microbes for xenobiotic biodegradation. Explosives impacts on biodiversity was illuminated and treatments protocol.

Keywords: fungi, bacteria, biodegradation, xenobiotic, characterization, explosives, military shooting range, horizontal gene transfer (HGT), 16srRNA gene sequence, PC3R technology

HGT, horizontal gene transfer; DNT, dinitrotoluene; EPA, environmental protection agency

Military ranges consist of regions designated for certain purposes, such as impact areas, guns and mortar firing positions, rocket ranges, and demolition areas. Due to the multiplicity of explosive compounds used, a variety of contaminants are spread out over the entire range. Several chemicals, such as 2,4,6 -trinitrotoluene (TNT), dinitrotoluene (DNT), RDX, HMX, and perchlorate can be expected in the soil at any given location in varying amounts. In general, concentrations of explosive compounds tend to decrease rapidly with depth and distance from detonation.1–50 Explosive residues have been a source of environmental contamination since World War II, when the production, storage, and testing of these materials commenced and is a concern of international importance.Energetic chemicals such as RDX and TNT can cause toxicity to plants and microorganismswhich inhabit directly polluted areas, and those regions exposed to contamination by offsitemigration of these compounds. Contaminated sites generally contain explosive materials in varying concentrations in soil, sediment, and ground water; this can have direct or indirect effects on human health. Many developing countries lack either the money or technology to clean-up the pollution from munitions residues.51–87

Explosives have been manufactured and employed in artillery since the 1930s, leading to the contamination of land and ground water at over 2,000 U.S. military sites.88–99 Two frequently used compounds are 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) and hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine, also known as Royal Demolition Explosive (RDX). RDX is a cyclic nitramine that is toxic to a wide variety of plants and mammals and is classified by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)as a Group C possible human carcinogen. Wastewater resulting from the production and improper disposal of explosives has collected in lagoons and serves as a source of highly concentrated RDX. Storage and testing of these energetic compounds has resulted in residual low concentrations (1.3 mg kg-1of soil) dispersed over large land areas, composed of soil and plant material.28,38 Due to its relative inability to cling to soil particles and its high mobility and slow volatilization from water, RDX contamination threatens drinking water supplies underneath contaminated soil beds.82

Explosives biodegradation

Military shooting ranges are vulnerable habitats to cyclic nitramine contamination, the microbes living in this environment consequently suffer from nitrate explosives passively, through the activities of indigenous chronic exposure. There have been several obstructions on the path to bioremediating these soils. First, evolutionary history has taught that microbes living in these contaminated soils would evolve abilities to utilize the nitrate explosives as substrates for survival.99 However, the indigenous microbes do not possess sufficient biomass or metabolic activity to degrade these xenobiotic before they leach through soils polluting ground water.92 Second, bioremediation techniques that involve inoculating non-indigenous microbes into contaminated zones for degradation are generallyout-competed by the indigenous bacteria, unless large amounts of substrates are added.12,66 Third, there is more than one compound in thesoil,100–130 which may prevent degradation if one or more compounds or metabolites present are toxic to the indigenous microbiota.92,131–147 Biodegradation of cyclic nitramines in soils on military ranges has involved both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria.

Rationale

Bioremediation refers to the use of biological agents to degrade or render various types of hazardous waste to a non-hazardous or less-hazardous state148–179 and has become an increasingly popular form of environmental detoxification in our progressively “green” society. Historically, in situ treatments such as pump-and-treat and bioventing, which treat the contaminatedsoils in place, have had problems succeeding in an uncontrolled environment.3 Since World War II, the use of energetic compounds by the military has resulted in large volumes of soil that are contaminated with explosives residue35 Cyclic nitramines, such as RDX, are resistant to degradation in soil and are highly mobile, thus threatening human health by leaching into ground water or to offsite locations, such as farmland.38,178 Characterization of site study microbes for potential xenobiotic biodegradation is the crux of the paper.

Study site

The study was conducted in the permanent military shooting/training range located at 5km east of Kachia town in Kaduna state, north central Nigeria (2015 - 2016). The range was established in 1965 and it covers an area of about 24. 95 square kilometres that lies between longitudes 9055’ N and 7058’ E, with an elevation of 732 meter above sea level and the topography is undulating and the vegetation is Guinea Savannah (Figure 1). The area where themunitions/explosive are fired (the impact area) is a valley consisting of about four large rocks, where the fired munitions/explosives land and explode during military training. Five military exercises involving the deployment of explosives are carried out annually by the Nigerian Defence Academy (NDA) Kaduna, Nigerian Air force (NAF) Kaduna, Nigerian Army School of Infantry (NASI) Jaji, Armed Forces Command and Staff College (AFCSC) Jaji and Nigerian Army School of Artillery (NASA) Kachia,Kaduna, Table 1.

|

N/S |

Explosives |

Wet season µg Kg-1 |

Dry season µg kg-1 |

|

1 |

TNT |

0.12 – 26.6 |

0.11 – 10.29 |

|

2 |

HMX |

1.43 – 68.19 |

0.39 – 35.67 |

|

3 |

RDX |

0.38- 15.33 |

0.49 – 68.19 |

|

4 |

PETN |

1.17 – 7.12 |

0.39 - 4.38 |

Table 1 Global positioning system (GPS) recorded in degrees, minutes and seconds (DMS) of sampling locations

Sampling points

Four sampling points selected for the study are locations 1, 2, 3 and 4, Table 2. Locations 1 and 2 are the twin smallest rocks closest to the road. While locations 3 and 4 are much larger rocks heavily impacted by munitions/explosives between locations 1and 2 is a flat ground where rain run offs flow through to the stream in this site (map with global positioning system (GPS) co-ordinates), Figures 1. Locations 1 and 2 approximately 200m from the Plateau that is where the small arms are fired such as FN, Kalashinokov, Greenad, GPMG, SMG and Pistols. The soil in locations 1 and 2 is made of 50% silt and a flat ground with shrubs and drainage that flow through to the farm lands near the sites. Location 3 is approximately 9000m away from the Plateau lies between 90 53’ 44.71” Northings and 70 53’ 17.87” Eastings. The impact area of locations 3 and 4 are mainly largely rocks containing high concentration of explosive due to the extensive use of bombardment by the artillery weapons, 155 mm nortwizer, and other heavy weapons while location 4 is ahead of location 3 is about 10,000m from the Plateau top where heavy weapons are fired too. The distance between locations 3 and 4 was covered with various shrubs and two major streams (Figure 1).

Locations |

Values |

Location (1) 0 metre |

30+35.29 |

Location (1) 200 meter |

4+2.94 |

Location (1) 400 metre |

27.33+36.04 |

Location (2) 0 metre |

30+30.59 |

Location (2) 200 metre |

2+1.41 |

Location (2) 400 metre |

3.67+3.77 |

Location (3) 0 metre |

12+16.971 |

Location (3) 200 metre |

24.33+20.07 |

Location (3) 400 metre |

12.331+13.91 |

Location (4) 0 metre |

11.33+5.79 |

Location (4) 200 metre |

1+ 0.33 |

Location (4) 400 metre |

1+ 0.12 |

Control |

3.67+2.49 |

Table 2 Bacterial isolates from twelve sampled locations in NASA, Kachia

Soil sampling

Sampling was done during both dry and wet seasons. Four locations located within NASA

(Table 1) shooting/training range Kachia were earmarked as sampling sites for this study using soil iron auger.10 gram of soil sample (0-30cm in depth) with diameter of 9 cm were collected from 3 different points within a location and harmonized to form a composite sample at various locations of the sites. All samples taken 2015 (June-August) and 2016 (Feb-March) and were sieved using a 63 (106 m) mesh size laboratory sieve and then stored in black labelled polythene bags until for analyses. Samples for microbial analyses were kept in a cool box refrigerated with ice pack to retain the original microbial activities.

Soil sample pre-treatment

Sampling points were treated in the laboratory before digestion as executed. 10 grams of the soil sample was weighed into a clean dried beaker and put into an oven at about 100°C for 1 hour. The soil sample was then ground in a porcelain mortar with pestle and sieved through 250 µg mesh size to obtain a homogenous sample. The soil sample was stored in sterilized polyethylene bags, label and kept for next stage of pre-treatment. This procedure was repeated for all the collected soil samples. The ground soil samples were used for analyzing heavy metal and explosives content for soil samples.90

DNA barcoding system characterization

DNA genome-based and DNA sequencing based technologies was used for the laboratory analyses, application of DNA sequence data, the ‘DNA barcoding’ system is providing a proficient place for species-level classification with the help of short sequences.108 Due to the genetic variation in the short unique sequence, it is useful for differentiating the individual species. Using these sequences, many efforts have been made in identifying different strains. These sequences can also be used for the development of barcode for microbial communities. These fragments of DNA sequences which are implemented for identification of unknown species are referred as DNA barcode and the system involved in recognition of alien strain is called as DNA barcoding.33 Also, Next, traditional method hasproblem in identification of cryptic species complex and sometime morphological keys used in identification may vary in particular life cycle arising difficulties in species identification. DNA barcode system is rapid tools and can classify large quantities of microorganisms at the same time, without any error.86 Using specific primer, target genes can be retrieved. The short fragment of DNA is amplified by using PCR. The amplicon obtained is then sequenced for bioinformatics analyses. The database using appropriate computer algorithm lead for identification of unknown strains (Figure 2).

In case of bacteria, 16SrRNA gene sequence (1500 bp nucleotide in length) is proven marker for species identification.81 The barcode marker sequence from each unidentified species is compared with a library of reference barcode sequences. The final goal of the DNA barcoding system is to build up a robust and efficient mechanism for the species identification in a rapid manner which should be simple and scalable.108 Evolution creates biodiversity in microbial communities. Gene sequence from DNA sample noted that the diversity of microbes is almost 100 times higher than what was projected by traditional microbiology. There is vast diversity in the communities of virus, bacteria, algae, fungi, and protozoa reported.180,181 The diversity of microorganisms can be identified with well-established marker genes through DNA barcoding system. DNA Bar-Code for Microbial Population. Bacterial diversity can be distinguished with 16SrRNA gene which is a universal marker for bacteria reported.182–212

COI gene is another DNA barcode developedfor bacteria which is 650 bp in length.118 Chaperonin-60 (cpn60) (known as GroEL 7 Hsp60), is a molecular chaperone conserved in bacterial strains that could be used as barcode marker for bacterial species identification.109 There are problematic boundaries for multitaxon evolutionary and biodiversity studies of fungi due to lack of simple DNA barcode marker. In recent days, fungal gene sequences are elevating in NCBI database. This made urge to scientist to perform taxonomical studies based on genomic criteria. Currently, mycological researches are also very keen for DNA barcoding of fungal species. ITS, LSU, SSU, RPB1, and COI are some of the examples of marker genes which can be introduced for fungus taxonomical studies213,214 reported illustrated a larger 1500 bp gene segment for Arbuscular mycorrhiza. The study presents SSUmCf-LSUmBr 1500 bp sequence as proven barcode fragments for identification of Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi.

Preparation of media

Nutrient agar: Nutrient Agar (Antec /USA) by dissolving 28g of the Agar in 1 litre of distilled water in a conical flask. The conical flaks with the media were autoclaved at 121°C at 15 pressure per square Index (PSI) for 15 minutes and cooled to 400C before pouring or dispensing if a sterile petri dishes.

MacConkey: MacConkey Agar was prepared by dissolving 49.53g of dehydrated medium in 1000ml distilled water in a conical flask. It was heated to dissolve the medium completely. The medium was sterilized by autoclaving at 15 1bs pressure (121°C) for 15 minutes and cooled to 45-50°C, mixed well before pouring into sterile petri plates.

Potato dextrote agar (PDA): Thirty nine (39) g of dehydrated medium suspended in 1000 ml distilled water was heated to dissolve the medium completely. It was then sterilized by autoclaving at 15 1bs pressure (121°C) for 16 minutes. Cooled ten percent (10%) of tartanic acid was added and mixed well to achieve pH 3.5 before dispensing into petri plates. The media were spread with the specimensoon after solidification of the media. Plates were incubated at 25-30°C in an inverted position (agar slide up) with increased humidity. Cultures were examined weekly for fungal growth and were held for 4-6 weeks.

Serial dilution: The sterile dilution blanks were marked in the following manner. 100 ml dilution blank was 102 and 9 ml tubes sequentially were 103, 104, 10-6 one gram of soil sample was weighed from each sample located and added to the 12-2 dilution blank and vigorously shaken for at least one minute with the cap securely tightened. All the 10-2 dilution was allowed to sit for a short period. The 1ml from this dilution was aseptically transferred to the 10-3 dilution was again transferred to the 10-4 dilution. The procedure was done to 10-5and 10-6. A flask of nutrient agar from the 45°C water bath was especially pounded into each petri plates for that set. 15ml was poured enough to cover the bottom of the plate and mixed with the 1 ml inoculum in the plate. Each set was gently swirled on the bench so that the inoculum gets thoroughly mixed with the ager. All the plates were allowed to stand without moving so that the agar solidified andsetcompletely. The plates were inverted and stacked into pipette carnisters and placed in the incubator or at room temperature until after 48 hours the same procedures were applied forMacConkey agarand Potato Dextrote Agar (PDA).

16S ribosomal RNA and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for amplification of catabolic genes

Sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based approaches (Figure 2). The concept of comparing gene sequences from microbial communities revolutionized microbial ecology. Subsequently, a suite of molecular methods was developed that employ rRNA sequences9,71,124 first described amplification of 16S-like rRNA from algae, fungi, and protozoa, and reports using 16SrRNA of bacteria and other eukaryotes soon followed.48,70,190,205 Bacterial diversity can be distinguished with 16SrRNA gene which is a universal marker for bacteria.182 These day mycological researches are also very keen for DNA barcoding of fungal species. ITS, LSU, SSU, RPB1, and COI are some of the examples of marker genes which can be introduced for fungus taxonomical studies.34,213 (Appendix).

Principle

PCR consist of an exponential amplification of DNA fragment and the principle is based on the mechanism of DNA replication in vivo, double stranded DNA is denatured to single stranded DNA, each single strand DNA is anneal by the forward and reverse primers of known sequence and elongated using tag DNA polymerase to produce copies of DNA template, Figure 2.

16srRNA Gene Sequences Result were aligned with BLAST search of NCBI Data bases

The bacterial 16s rRNA gene sequence result were aligned with BLAST search of NCBI data bases. The sequences aligned 99% result similarity with Lysinibacillus, Esherichiacoli, Achromobacter, Enterobacter and Bacillusspp while Arcobacter and Klebsiella spp had 98% similarity. In this result different species of bacteria strains involved in munitions/explosive degradation were highlighted. (Figure 6)

Achromobacter spp

ACGCTAGCGGGATGCCTTACACATGCAAGTCGAACGGCAGCACGGACTTCGGTCTGGT

GGCGAGTGGCGAACGGGTGAGTAATGTATCGGAACGTGCCTAGTAGCGGGGGATAACT

ACGCGAAAGCGTAGCTAATACCGCATACGCCCTACGGGGGAAAGCAGGGGATCGCAAG

ACCTTGCACTATTAGAGCGGCCGATATCGGATTAGCTAGTTG

Lysinibacillus spp.

GCCTAATACATGCAAGTCGAGCGATCAGAGAAGGAGCTTGCTCCTTATGACGTTAGCG

GCGGACGGGTGAGTAACACGTGGGCAACCTACCCTATAGTTTGGGATAACTCCGGGAA

ACCGGGGCTAATACCGAATAATCTATGTCACCTCATGGTGACATACTGAAA

Escherichia spp

TCGCTGACGAGTGGCGGACGGGTGAGTAACGTCTGGGAAACTGCCTGATGGAGGGGGA

TAACTACTGGAAACGGTAGCTAATACGCGATAACGTCGCAAGACCAAAGAGGGGGACC

TTCGGGCCTCTTGCCATCGGATGTGCCCAGATGGGATTAGCTAGTAGGTGGGGTAACG

GCTCACCTAGGCGACGATCCCTAGCTGGCTTGAGAGGATGACCAGCCACACTGGAACT

GAGACACGGTCCAGACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGTGGGGAATATTGCACAATGGGCGC

AAGCCTGATGCAGCCATGCCGCGTGTATGAAGAAGGCCTTCGGGTTGTAAAGTACTTT

CANCGGGGAGGAAGGGGAGTAAAGTTAATACCTTGTCTCATTGA

Klebsiella spp

TACTGGAAACGGCAGCCAATACCGCATAACGTCGCAAGACCAAAGAGGGGGACCCTT

TCGGGCCTCTTGCCATCGGATGTGCCCAGATGGGATTAGCTAGTAGGTGGGGTAACG

GCTCACCTAGGCGACGATCCCTAGCTGGTCTGAGAGGATGACCAGCCACACTGGAAC

TGAGACACGGTCCAGACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGTGGGGAATATTGCACAATGGGC

GCAAGCCTGATGCAGCCATGCCGCGTGTATGAAGAAGGCCTTCGGGTTGTAAAGTAC

TTTCANCGGGGAGGAAGGGAGTAAAGTTAATACCTTTGCTCATTGA

Bacillus spp

GCGAACGAGAAGGAGCTTGCTCCTTTGACGTTAGCGGCGGACGGGTGAGTAACACGT

GGGCAACCTACCCTATAGTTTGGGATAACTCCGGGAAACCGGGGCTAATACCGAATA

ATCTATGTCCCCTCATGGTGACATACTGAAAGACGGTTTCCG

Arcobacter spp

CCTAACACATGCAAGTCAGAACGGCTACGCACGAGACGTATCGGTCTGGTGGCAGA

GTGGCGAACGGGTGAGTAATGTATCGGAACGTGCCTAGTAGCGTGGGGATAACAAC

GCGACAAGCGTAGCTAATACCGCATACGCCCTACGGGGGAAAGCAGGGGATCGCAA

GACCTTGCACTATTAGAGCGGCCGATATCGGATTAGCTAGTTGGTGGGGTAACGGC

TCACCAAGGCGACGATCCGTAGCTGGTTTGAGAGGACGACCAGCCACACTGGGACT

GACGACACGGCCCAGACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGTGGGGAATTCTTGGACAATGG

GGGAAACCCTTGATCCCCGCCCTTCCCGCGTTGTGCGATTCGACCCGCTTTCTTG

Enterobacter spp

CGGTAACAGGAANCANGCTTGCTGCTTCGCTGACGAGTGGNGGACGGGTGACTAAT

GTCTGGGAAACTGCCTGATGGAGGGGGATAACTACTGGAAACGGTAGCTAATACCG

CATAACGTCGCAAGACCAAAGAGGGGGACCTTCGGGCCTCTTGCCATCGGATGTGC

CCAGATGGGATTAGCTAGTAGCTGGGGTAACGGCTCACCTAGGCGACGATCCCTAG

CTGGTCTGAGAGGATGACCAGCCACACTGGAACTGAGACACGGTCCANACTCCTAC

GGGAGGCAGCAGTGGGGAATATTGCACAATGGGCGCAAGTCC(Figure 7) (Table 9)

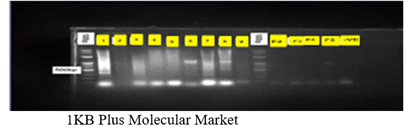

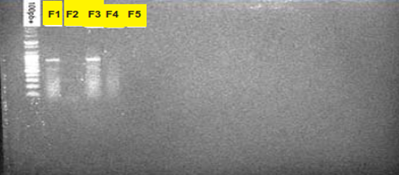

Isolated explosive fungi DNA were amplified using catechol 2,3 dioxygenase gene primers. The genomic DNA, the primers and PCR master mix were added into a PCR tube. The tubes were spun to collect the droplets. The tubes were then inserted into the PCR machine while maintaining the regulation for initial denaturation (45 seconds at 94°C), annealing (1 minute at 55°C) extension (1 minute at 72°C) and final extension (10 minutes at 72°C). The amplified catabolic genes were resolved in 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis stained with ethidium bromide and viewed under ultra-violet (UV light). The PCR reaction mixture containing 10 X PCR buffer, 25mm, magnesium chloride, 25mm dNTP’s, 10pm/uL primer concentrations and template DNA were used for the amplification of the 16srRNA gene for each isolates. PCR conditions were optimized using lab net thermal cycler. The PCR Program began with an initial 5-minuites denaturation step at 94°C: 35 cycles of 94°C for 45 seconds, annealing (1 minute at 55°C), 10 minutesextension step at 72°C. All reaction mix were preserved at 4°Cuntil it was time for analysis as reported.104 The amplified 16srRNA gene of each isolates was further characterized using gel electrophoresis, Plate 1. The amplified 16srRNA gene of each isolate was processed for sequencing and characterization. The sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) with the product was analysed with ABI prism DNA sequence (ABI). The gene sequence of each isolates obtained in this study (Plate 1) were compared with known 16srRNA gene sequences in the Gene Bank database as reported.94

Plate 1 Amplification of catechol 2, 3 dioxygenease from both bacteria and fungi isolates. Lane of 100bp

– DNA marker (Ladder) Lane I -Bacillus spp, Lane 3 Arcobacter spp, Lane 4 - Klebsiella spp, Lane 5 -Achromobacter spp, Lane 6 -Escherichia spp, Lane 7 – entrobacter spp, Lane 8 - Lysini Bacillus spp, Lane F1 - Aspergillus niger, Lane F2 - Rhizopus spp, Lane F3 - Penicillium spp, Lane F4 -Trametes versicolor and Lane F5 - Phanorochate chrysoporium.

Fungi species isolation of genomic DNA

The genomic DNA of each fungus with observed remediation capabilities was isolated. 1 ml of each fungal culture was pelleted by centrifuging at 12,000 rpm for 2 minutes; the pellet was treated with Iysis solution and proteinases K and incubated at 60°C for 30 minutes. Deoxyribose nucleic acid (DNA) was extracted from each fungus precipitated with isopropanol by centrifuging at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes, washed with 1 ml of a 70% (v/v) ethanol solution and dissolved in 0.1 ml of a T.E buffer. The purity and quantity of (DNA) of each sample was examined using UV absorption spectrum and agarose gel (1%) electrophoresis as described by94,183 and Plate 1 and Table 7. Fungi species genes are present in multiple copies and contain conserved coding (small subunit - SSU and large subunit - LSU) as well as variable non-coding parts (internal transcribed spacers - ITS). Thus, they are useful to distinguish taxa at many different levels155 and see Figure 3.

Bacteria species characterization

Nutrient agar: Nutrient Agar (Antec / USA) by dissolving 28g of the Agar in one litre of distilled water in a conical flask. The conical flaks with the media was autoclaved at 121°C at 15 Pressure Per Square much (PSI) for 15 minutes. Cooled to 40°C before pouring or dispensing if a sterile petri dishes.

MacConkey agar: MacConkey Agar was prepared by dissolving 49.53g of dehydrated medium in 1000 ml distilled water in a conical flask. It was heated to dissolve the medium completely. The medium was sterilized by autoclaving at 15 1bs pressure (121°C) for 15 minutes. Cooled to 45-50°C, mixed well before pouring into sterile petri plates.

Potato dextrote agar (PDA): Thirty-nine (39) g of dehydrated medium suspended in 1000 ml distilled water was heated to dissolve the medium completely. It was then sterilized by auto clavingat 15 1bs pressure (121°C) for 16 minutes. Cooled ten Percent (10%) of tartanic acid was added and mixed well to achieve pH 3.5 before dispensing into petri plates. The media were spread with the specimen soon after solidification of the media. Plates were incubated at 25-30°C in an inverted position (agar slide-up). With increased humidity. Cultures were examined weekly for fungal growth and were held for 4-6 weeks.

Serial dilution

The sterile dilution blanks were marked in the following manner. 100 ml dilution blank was 102and 9ml tubes sequentially were 103, 104, 10-6. One gram of soil sample was weighed from each sample located and added to the 12- dilution blank and vigorously shaken for at least one full minute with the cap securely tightened. All the 10-2 dilution was allowed to sit for a short period. The one ml from this dilution was aseptically transferred to the 10-3dilution was again transferred to the 10-4 dilution. The procedure was done to 10-5and 10-6. A flask of nutrient agar from the 45°C water bath was especially pounded into each petri plates for that set. 15 ml was poured enough to cover the bottom of the plate and mixed with the one ml inoculum in the plate. Each set was gently swirled on the bench so that the inoculum gets thoroughly mixed with the ager. All the plates were allowed to stand without moving so that the agar solidified and set completely. The plates were inverted and stacked into pipette carnisters and placed in the incubator or at room temperature until after 48 hours the same procedures were applied for MacConkey and PDA and see Figure 3.

Characterization of bacterial isolates gram staining

Thin smear of colony from the petri dish containing the bacterial culture was prepared. The smears were air dried and heat fixed using slide rack. The smears were stained with crystal violet for 30 seconds, each slide was washed with distilled water for a few seconds using wash bottles and then each smear was treated with gram’s iodine solution for 60 seconds. The iodine solution washed off with 95% ethyl alcohol. Ethyl alcohol was added drop by drop, until no more colour flows from the smears. The gram positive bacteria were not affected while all gram negative bacteria were completely decolorized. The slides were washed with distilled water, allowed to be drained and treated with safranin smears for 30 seconds and was washed with distilled water and blot dry with absorbent paper and the stained slides was allowed to air dry. The bacterial that retained the primary stain (crystal-violet) were gram positive and those that do not retain the primary stain were Gram-negative. The slides were examined microscopically using oil immersion objective. Bacterial colonies were identified by Gram’s staining and biochemical characterization according to Bargy’s Manual, Figure 2.

Cultural morphology of bacteria isolates

Isolated colonies of each bacteria were absorbed and culturally morphologically based on their superficial forms (circular, filamentous and irregular) elevation (flat, convex and umbonate), Margin (Lobate, convex or irregular), and shape spiral, rod or cocci using hand magnifying lens, Tables 4&5.

Citrate test: The simmons create agar medium contains the pH indicator bronollymol blue and medium citrate as the sole sources of carbon. Citrate is an enzyme found in some bacteria. Citrate is breakdown by citrate to oxaloactic acid and acetic acid. The breakdown is indicated in the medium by the change of colour from green to blue. However, the removal of citrate from the medium by bacteria that can utilize citrate creates an alkaline condition in the medium and indicator changes to its alkaline colour blue. The test organism was inoculated into simmon’s citrate agar Slants and incubated at room temperature for 24 hours. Colour change from green to blue indicated a positive test while no colour change indicated a negative result (Table 2).

Coagulase test: Coagulase is an enzyme aureus in staphylococci aureus that causes the conversion of soluble fibrinogen into insoluble fibrin. The reaction is different from the normal clothing mechanism exhibited in blood clothing. Gram positive staphylococci that produced catalase positive reaction were further tested for coagulase. 0.5ml suspension of a 24 hours broth culture of the bacteria was mixed with 1ml of anticoagulant containing blood plasma in a testtube. This was incubated at room temperature and positive coagulase bacteria revealed the formation of fibrin cloths in the test-tubes. Positive coagulase is a characteristic of staphylococcusaureus aura.113

Motility indole orinthine agar

Motility can be determined from Brownian motion (small, random movement) exhibited by the bacteria in the medium. Trptophanase is oxidized by an enzyme trypotophanase in some bacteria to produce indole pyruvate react with Kovaes, reagent (dimellhycamino-benzaldehyde) to form resounded (cherry red compound) and water. Bacteria with Ornithine decarboxylase will decorboxylate the amino acideornithine into purescine. The medium which contains bromcyresol purple with turn yellow after the enzyme inedecarboxylateornithine. The amino acid ornithine into putrescine. The medium which contains bomcresol purple will turn yellow after the enzymedecarboxylate ornithine. Motility indole ornithine (M10) medium was used to determine motility and indole production. Ten (10) ml of the medium was dispensed into atest-tube and autoclaved. Each pure colony of the unidentified organism was stabbed into the test tube using a sterilized wire loop and incubated at room temperature for 24 hours. Motility was observed as hazy diffuse spreading growth (Swarm) along the stab unlike non mortals, restricted to the stab line. The presence of ornithine decarboxylase is observed when the purple colour of the medium changes to yellow.26 For indole production 2-3 drops of Kovac’s reagents (Dimellylamino-benzylaldehyde) was added to the medium in the test tube. A red precipitate at the top of the interface indicated a positive reaction of indole production. For Ornithine decarboxylasereaction.147

Methyl red test

Some bacteria produce large amount of organic acids such as formic, lactic acid and succinic acid. These organic acids react with methyl red resulting in red coloration of the medium. The test was conducted to detect the production of sufficient acid by fermentation of glucose so that pH dropped to 4.5.The test organism was inoculated in glucose phosphate broth and incubated at room temperature for 2-5 days. Five drops of 0.04% solution of methyl red were added and mixed well. A bright red colour indicated a positive result while a yellow colour indicated a negative result.

Characterization of isolates of explosive degrading fungi from Kachia firing range

Five (5) fungal genera were isolated in all the twelve sampled NASA shooting range. The growth appearances of those fungal Isolates observed on Potato Dextrote Agar (PDA) were dark, pigment, grey or, Yellowish green to dark green, yellowish-brown dark grey centre withlight periphery, mycelia and spore’s Microscopic examination of acid fuschin stain of the fungal isolate revealed probable features of Rhizopus spp, Aspergillus niger, Penicillium sp Trametes versicolour, and Phanorochate chrysoporium, Table 3 & Figure 3.

Parameters |

Unit |

Wet |

Dry |

Mean |

Parameters |

OC or OF |

27.16 |

22.71 |

24.94 |

Parameters |

EC µs/cm |

6.07 |

2.31 |

4.19 |

Parameters |

EC µs/cm |

3011 |

312 |

1661.5 |

Parameters |

(mg/L) |

513.1 |

347.7 |

347.7 |

Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) |

% |

5.11 |

5.76 |

5.44 |

Available phosphorus |

(mg/kg) |

4.7 |

4.9 |

4.8 |

Total Nitrogen |

% |

9.32 |

9.72 |

9.52 |

Sodium conc |

ppm |

498 |

863 |

680.5 |

Potassium conc (ppm) |

ppm |

169 |

162 |

165.5 |

Sulphur conc |

ppm |

560 |

724 |

642 |

Carbonate (C03-2) |

mg/100g |

0.22 |

0.35 |

0.285 |

Bicarbonate (HC03) |

mg/100g |

1.11 |

1.68 |

1.4 |

Manganese |

mg/kg |

75.01 |

75.01 |

79.1 |

Moisture |

% |

59.56 |

59.56 |

35.87 |

Water holding capacity |

% |

59.56 |

51.12 |

55.34 |

Porosity |

% |

56.27 |

69.39 |

62.83 |

Table 3 Meanseasonal variation of physcio-chemical parameters of composite samples of four firing range locations (12 different metres)

Polymerase chain reaction amplification isolation of genomic DNA from bacteria

Bacteria with proven bioremediation capacity (also efficient strains of these bacteria) was selected and the DNA isolated. DNA of bacteria strains isolated was extracted from 1ml of bacteria culture, the culture was pelleted by centrifuging at 12,000 rpm for 2 minute. the pellet was treated with lyses solution and proteinase K and incubated at 60°C for 30 minutes. Nucleic acid was precipitated with isopropanol by centrifuging at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes, washed with 1 ml of a 70% (v/v) ethanol solution and dissolved in 0.1ml of a TE buffer. The purity and quantity of DNA were examined by recording its agarosegel electrophoresis.94,183 The PCR reaction mixture containing 10X PCRbuffer, 25 mm, magnesium chloride, 25 mm dNTP’s, 10pm/uL Primer concentrations and template DNA were used for the amplification of the 16srRNA gene for each isolates.PCR conditions were optimized using lab net thermal cycler. The PCR program began with an initial 5-minutes denaturation step at 94°C: 35 cycles of 94°C for 45 seconds, annealing (1 minute at 55°C), 10 minutes extension step at °C All reaction mix were preserved at 4°C until it was time for analysis as reported.104 The amplified 16srRNA gene of each isolates was further characterized using gel electrophoresis.

The amplified 16srRNA gene of each isolate was processed for sequencing and characterization. The sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) with the product was analysed with ABI prism DNA sequence (ABI). The gene sequence of each isolates obtained in this study were compared with known16srRNA gene sequences in the Gene Bank database as described.94 16srRNA gene band size of 100b was observed for each bacteria on the agarose gel isolates from each munition contaminated site (Figures 1&3). Meanwhile, the identity of the isolates was further confirmed by 16srRNA sequencing and BLAST.8The amplified 16srRNA gene of each isolates were further characterized using gel electrophoresis (Appendix 3). Catechol 2, 3, dioxygenase band size of 100 bp was detected in Lysinibacillus Escherichia coli, Achromobacter, enterobacter, and Bacillus spp. The other bacterial and fungal isolates showed no band which implies the absence of catechol 2, 3 dioxygenase gene,see Plate 1 and Table 4 respectively.

|

OD Values in Days |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bacterial Species |

0 |

2 |

4 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

12 |

14 |

16 |

Lysini Bacillus |

0 |

0.021bcd |

0.037abc |

0.038b |

0.054b |

0.080a |

0.199b |

0.115a |

0.098a |

Achromobacter |

0 |

0.001d |

0.010dc |

0.016cd |

0.053b |

0.036c |

0.63a |

0.072e |

0.066f |

Escherichia coli |

0 |

0.034abc |

0.056a |

0.061a |

0.069a |

0.073b |

0.098b |

0.099c |

0.078c |

K. pneumonia |

0 |

0.06a |

0.024cd |

0.031cb |

0.043c |

0.050d |

0.069c |

0.080d |

0.069f |

B. subtilus |

0 |

0.04ab |

0.05ab |

0.05ab |

0.030e |

0.072b |

0.078c |

0.084c |

0.080b |

Arcobacter spp. |

0 |

0.01cd |

0.031bcd |

0.043ab |

0.045c |

0.054d |

0.059c |

0.067f |

0.061g |

Entrobacter Spp. |

0 |

0.03bc |

0.04abc |

0.05ab |

0.036d |

0.063c |

0.078c |

0.097b |

0.068f |

MBC |

0 |

0.020bcd |

0.029bcd |

0.043ab |

0.057b |

0.070b |

0.075c |

0.118a |

0.073e |

Control |

0 |

0.000d |

0.002e |

0.004d |

0.007f |

0.007f |

0.001d |

0.004g |

0.001h |

Table 4 Gram stain result, morphological and biochemical characterization of the different microbial Isolates from the NASA shooting range Kachia Kaduna

+=Positive (means present), - =Negative (means absent)

NB: TNT – 2, 4, 6 – trinitrotohience, Royal Demolition Explosive (RDX) – 1,3,5 frinitro - 1,3,5 – trazinanze, HMX – 1,3,5 tetranitor 1,3,5 – tetrazocalne, High Melting Explosion - BDL (Below Detectable level).

Isoaltes frequency |

Location 1 |

|

Location 2 |

|

Location 3 |

Location 4 |

|

Percentage % |

|||||

Bacillus S |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

50 |

Escherichia coli |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

33 |

K. pneumonia |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

50 |

|

Entrobacter Spp. |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

75 |

Aspergillus niger |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

67 |

Penicillium spp |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

17 |

T.vesicolor |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

17 |

Phanerochaetechrysosporium |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

33 |

Rhizopus spp. |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

50 |

Table 5 Characterization of microbes at the Kachia, Kaduna, Nigeria shooting range

Analysis of environmental sequences

The identity of an environmental sequence is obtained after a homology search of genetic databases, such as Genbank at the National Centre forBiotechnology Information (NCBI, http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/)and ones held at the EuropeanBioinformatics Institute (EMBL-Bankhttp://www.ebi. ac.uk/embl/), the Ribosomal Database Project (http://rdp.cme. msu.edu/; and the AFTOL project (http://aftol.biology.duke.edu/pub/ blast Upload.

Amplification of catechol 2, 3 dioxygenease from both bacteria and fungi isolates. Lane of 100bp – DNA marker (Ladder) Lane I - Bacillus spp, Lane 3 - Arcobacter spp, Lane 4 - Klebsiella spp, Lane 5 -Achromobacter spp, Lane 6 -Escherichia spp, Lane 7 –entrobacter spp, Lane 8 - Lysini Bacillus spp, Lane F1 -Aspergillus niger, Lane F2 - Rhizopus spp, Lane F3 -Penicillium spp, Lane F4 -Trametes versicolor and Lane F5 -Phanorochate chrysoporium. This involves using a computer algorithm to search the database for similar sequences by aligning the un- known sequence with those held in the database. Searches performed by the BasicLocalAlignment Search Tool (BLAST) at the NCBI return results listing the probable matches to the unknown with sequence similarity values.

Isolated bacteria and fungi from various locations of NASA Shooting range bacterial counts (X103) of NASA shooting range Kachia are presented in Table 2. The bacterial loads of the soil ranged between 30±35.59 and 30±30.59 cfu/ml in both locations (1) metre and (2) 0 metre and 1±0.33 and 1±0. 12 cfu/ml in both locations (4) 200 metre and 400 metre respectively. The bacterial load of locations (1 and 2) 0 metres were highest (30±35.59 and 30±30±59 cfu/ml) and that of the location (4) 200 and 400 metres respectively was lowest 1±0.33 and 0±0 cfu/ml with respect to the control 3.67±2.49, Table 2. Fungal loads (X 105) obtained from NASA shooting range Kachia are presented in Table 3. Soil samples collected from location (2) 200 metre and location (1) 0 metre had fungal counts of 3±56.33 and 27.71±1.10 cfu/mlrespectively with respect to the control was 1±3.43 cfu/ml. The highest bacterial load and fungal load in the impact area was due to the high concentration of munitions contaminations with a distance of zero metre compare to the distance 200m and 400m that is far away from the control and similar to a report92 that pollutants concentration reduces from the source pint of the pollutant. The bacterial and fungal load in the control was very low compared to the munitions contaminated sites, Tables 2&3 respectively.

Gram stain, morphological and biochemical characteristic of the microbialisolates

Table 4 shows the Gram stain, morphological and biochemical characteristic of the microbial isolates from the twelve locations in the Study sites. The Gram negative isolates comprised of the genera Escherichia, Enterobacter, Klebsiela, Bacillus and Pseudomonas. Only Bacillus was found to be gram positive while others were gram negative. The colonial morphologies of all the isolates were examined with characteristics including shape, texture, size colour, margin elevation and opacity. The forms of the colonies of bacterial isolates were mostly Rod and few were cocci. The surface characteristics of bacterial cells were found to be smooth, rough, glistering and shinny. While, most of the colonies selected visually based on naked eyes observation were of whitish, green and grey coloration. Margin of colonies of bacterial isolated were found in rice. The colonies were observed mostly to be opaque, transparent and moist. Results of the gram staining investigation on the various colonies revealed that all the bacteria cells where gram negative with the exception of Bacillus that was gram positive, Table 4. Average Colonial Count of Bacteria and Fungi Isolates from Twelve Locations Table 4 shows the result of bacteria and fungi colonial count from the cultured soil sampled obtained from twelve investigated locations in NASA shooting range Kachia Kaduna. Bacteria had the highest loads of 75% in Enterobacter while and E. coli had the lowest percentage occurrence of 33%. Similarly, in fungal loads, Aspergillus spphad the highest percentage occurrence of 67% while Penicillium and Trametes spp had the lowest percentage occurrence of 17% respectively.

Bacteria 16srRNA gene sequences

The bacterial 16srRNAgene sequence results were aligned with BLAST search of NCBI data bases from Table 2. The sequences aligned 99 % result similarity with Lysinibacillus, Esherichia coli, Achromobacter spp,Enterobacter spp and Bacillus spp while Arcobacter spp and Klebsiella spp had 98% similarity. In this result different species of bacteria strains involved in munitions/explosive degradation were highlighted (Figure 3).

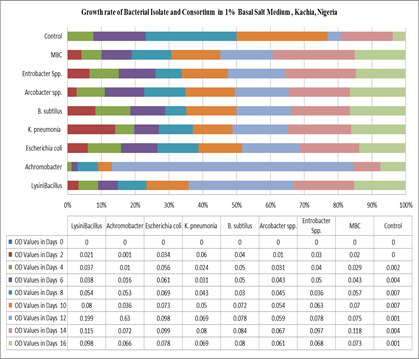

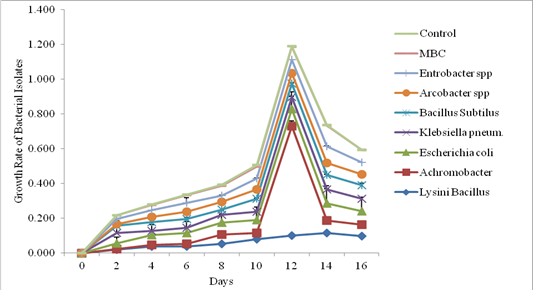

Figure 3 The growth potential of explosive utilizing bacteria (explosive by turbidometry) reported by Otaiku and Alhaji, 2020 at the same study site.

Findings

The biodegradability of in situ microbes by same authors143 in the study site (Table 2) by Turbidometry Figure 4 shows the optical density reading of biodegrading activity of each bacterial isolate on explosivesbroth with 1% exposure mineral salt medium(MSM). The results revealed that the bacteria Lysinibacillus spp, Achromocter spp, E. coli, Klebsiella pneumonia, Bacillus subtilis, Arcobacter spp and Enterobacter spp, had the ability to degrade explosives. The results of analysis show that there is a significant difference in the overall growth rate reading at 595 nm for 14 days of incubation, Figure 5. The overall results also indicated that growth rate increase significantly from the 8th to 14th day Achromobacter and Arcobacter had Lag, exponential, stationary and death phases143 on the same study site .Lysinibacillus, E. coli and microbial bacteria consortium (MBC) growth rate observed was exponential, stationary and death phases while Bacillus subtilis, Klebsiella Pneumonia and Enterobacter spp. exhibited stationary, exponential and death phases reported.143

Figure 4 The bacterial consortia in 1% Explosive Mineral Salt (Basal Salt Medium) mean value) reported by Otaiku and Alhaji, 2020 at the same study site.

The test on the degrading activity of isolates on explosive show that bacteria genus Lysinibacillus, Achromobacter pp, E.coli, KlebsiellaPneumonia, Bacillus subtilis, Arcobacter spp, Enterobacter sppand MBC were potent degraders of explosive with MBC (Figure 5)>Lysinibacillus >E.coli >Enterobacter spp >Bacillus subtilis >Klebsiella pneumomia >Achromobacter >Arcobacter spp with optical density values of 0.182, 0.118, 0.099, 0.097, 0.084, 0.080, 0.072 and 0.067 respectively. Isolated fungi (Aspergillus spp, Penicillium spp, Rhizopus spp, Trametes versicolor and Phanorochate crysoporium) microbes xenobiotic explosivesbiodegradation reported144 on the same study site which demonstrated that lignolytic fungi such as Penicillium spp. Aspergillus spp, Rhizopusand phanerochate chrysoporiuma white dot fungus was capable of oxidizing cyclic nitramines and mineralizing RDX and HMX. This is in conformity with164 Where the fungus mineralizing 52.9% of an initial RDX concentration in 60 days in liquid culture to mainly Co2 and N20. And 20% of an initial HMX concentration in 58 days when added to soil slurries of ammunition contaminated soil to yield the same N product.60 Similarly, Aspergillus spp, Rhizopus spp, Penicillium spp and Tramets Versicolorisolated in the study sites in Plate 2. Collaborated the finding75 for having biodegradation potentials on heavy metals Cd, Zn, Co, Pb, Cu, Ni,Table 7.

Plate 2 F (fungal lane of 100bp-DNA marker) F1 Rhizopus spp, F2 Aspergillus niger, F3 Penicillium spp, F4 Trametes versicolour, and F5 Phanorochate chrysoporium isolates, Kachia, Kaduna, Nigeria. 16srRNA gene amplification from the isolated munitions/explosive degrading fungi genera Kachia, Nigeria.

The ability of fungi to produce extracellular enzymes and factors that can degrade complex organic compounds has also sparked research on their use in decontamination of explosives-laden soils and waters.69 The filamentous white-rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium has been shown to hydrolyze the nitrate ester nitroglycerin (glyceryl trinitrate). As long as the nitroglycerin extracellular concentration was under the lethal dose, metabolite formation and regioselectivity depend nature of the strains used. Explosives bioremediation by bacteria is possible by phenomena of horizontal gene transfer (HGT). HGT occurs when DNA is released from a cell and transformed into another cell. DNA release may result after bacterial death following infection by bacteriophages, or through the release of plasmid and chromosomal DNA by living bacteria.138 Released DNA binds to soil particles and humic substances in the soil and is protected from enzymatic degradation. Transformation of the DNA into another host occurs when a susceptible bacterium comes into contact with the soil-DNA complex139 Over a long period of time in the firing range soil community, HGT will enhance the microbial diversity through increased microbial fitness.137 This may allow bacteria to acquire the genes necessary for explosives remediation as reported143 on bacteria xenobiotic biodegrading of same study site.

Soil containing 12% or less explosive concentration has been shown to pose no detonation or explosive threat when heated under confinement. Human health concerns may arise through the exposure of residual explosives via dust inhalation, soil ingestion and dermal absorption. TNT and RDX are classified as possible carcinogens while TNT-metabolites 2,4-DNT and 2,6-DNT are classified as probable human carcinogens. Other health effects reported as a result of exposure to residual explosives include skin haemorrhages, liver abnormalities, anemia and convulsions. Nitramine explosives such as RDX and HMX are reported to have lower affinities for sorption to inorganic soil components than the nitroaromatic explosive TNT.111 Clay soils also allow for high sorption of TNT.52 Soil composition can be a factor in the transformation of residual explosives into their metabolites as reported for vermiculite soils promoting the transformation of TNT.91 High sorption will allow for the persistence of contamination in the soil and increase the potential for detrimental exposure when it is desorbed. Morphological and biochemical characterization, Table 4. Bacteria (Appendix) andfungi isolates impact on heavy metal biodegradability, Table 9 & Figure 6.

The bacteria andfungi isolates impact on heavy metal biodegradability, Table 6. Further studies on TNT-contaminated soils via 16SrRNA gene sequence alignments confirm the role of Pseudomonas on the species level as Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This species was able to survive in media spiked with up to 50 mg/L of TNT with no adverse effects on its growth rate. Other species of Pseudomonas that are able to grow in the presence of TNT include P. savastanoi, P. fluorescens, P. chlororaphis, P. putida, and P. marginalis.115 Bacteria such as Desulfovirio spp. are able to further reduce TAT, which results in the production of toluene.24 Pseudomonas capable of using the substrate as its sole source of carbon and energy.168 Culturing methods were used to identify RDX degraders from an explosive contaminated site as Morganella morganii, Providencia rettgeri and Citrobacter freundii.102 There have also been numerous metagenomic studies to identify RDX metabolizing bacteria for possible bioremediation purposes. Bacteria in a groundwater sample contaminated with RDX were identified at the genus level through DGGE. Predominant genera were Pseudomonas sp.,Rhodococcus spp., Enterobacter spp., Shewanella spp., Clostridium spp.68 Toxicity of heavy metals to life forms in Kachia, Kaduna, Nigeria, Table 7. Fungi Isotates Implicated in Biotransformation and Mineralization. Kachia, Kaduna, Nigeria, Table 8. Characterization of microbes at the Kachia, Kaduna, Nigeria shooting range, Table 4.

|

Microbial isolated species |

Gram± |

Occurrence |

Remediating Metals |

References |

|

Bacillus spp |

CU |

Chatterjee et al.32 |

||

|

Cu, Zn, Cd, Pb, Fe, Ni, Ag, Th |

||||

|

Escherichia coli |

Gran (-ve) |

Cd , Zn and V |

Grass et al.78 |

|

|

Gram (-ve) |

Soil |

Ni , Cr(VI) |

Liizaroaie |

|

|

Pseudomonas spp. |

Gram (-ve) |

Soil and sediments |

U accumulator |

Sar & D'Souza |

|

Pseudomonas spp. |

Gram (+ve) |

Wastewater |

Cr(VI) |

Srivastava et al.173 |

|

Acenetobacter spp. (OKl) |

Gram (-ve) |

Water and soil |

Hydrocarbons (Petroleum) |

Koren |

|

Phanerochaetechrysosporium |

Fungi |

Soil |

Polyethylene, polypropylene |

Zhou et al.214 |

|

Fungi |

Soil |

4,4 dibmmodiphenyl ether |

||

|

Rhizopus spp. |

Fungi |

Soil |

Cr(VI) |

Bai14 |

|

Penicillium spp |

Fungi |

Soil |

Pb, Fe, Ni, Ra, Th, U, Cu, Zn, |

Selatnia et al. |

|

Aspergillus niger |

Fungi |

Zn |

Nweke et al. |

|

|

Pb, Zn, Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni and |

Muraleedharan& Venkobachar134 |

|||

|

Zn Chlorpyrifos |

Ahluwalia & Goyal4 |

|||

|

Uranium |

Mukherjee & Gopal132 |

|||

|

|

|

Soil and sediments |

Cr(VI) |

Goyal et al.4 |

Table 6 Bacteria and fungi isolates impact on heavy metal biodegradability

|

Metal |

Effects on human |

Effects on plants |

Microorganisms impacts |

Fungi isolates bioremediation |

References |

|

Cadmium |

Bone disease, coughing, emphysema |

Chlorosis, decrease in plant nutrient |

Damage nucleic acid. |

Asp .sp>Rhzsp>Pen sp.>T.Vesicolor> |

Fashola, et al.,56 |

|

headache, hypertension, etc. |

Inhibits metabolism. |

>P.chrysoporium |

|||

|

Arsenic |

Brain damage, cardiovascular and |

Physiological disorders |

Deactivation of enzymes |

P.chrysoporium>T.vesicolor> |

Abdul-Wahab1 |

|

conjunctivitis, dermatitis, skin cancer |

Loss of fertility, Inhibition of growth, Destroy metabolic processes |

Pen sp.>Asp .sp>Rhzsp |

Finnegan & Chen44 |

||

|

Copper |

Abdominal pain, anemia, diarrhea, |

Chlorosis, oxidative stress, |

Disrupt cellular function, |

T.vesicolor>P.chrysoporium>Asp . sp> |

|

|

kidney damage, metabolic disorders, |

retard growth |

inhibit enzyme activities |

Rhzsp>Pen sp. |

||

|

Chromium |

Bronchopneumonia, chronic bronchitis, |

Chlorosis, delayed, senescence |

inhibition of oxygen uptake |

P.chrysoporium>T.vesicolor>Asp . sp> |

|

|

reproductive toxicity, lung cancer, |

stunted growth, oxidative stress |

Pen sp.>Rhzsp |

Cervantes30 |

||

|

Lead |

Anorexia, chronic nephropathy, insomnia, |

reduce enzyme activities |

Denatures nucleic acid and |

P.chrysoporium>T.vesicolor>Rhzsp> |

Mupa133 |

|

damage to neurons, risk Alzheimer ’s disease, |

Affects photosynthesis and growth, |

inhibits enzymes activities |

Pen sp.>Asp .sp |

Wuana& Okieimen206 |

|

|

Nickel |

Cardiovascular diseases, chest pain, dermatitis, |

reduced nutrient uptake |

Disrupt cell membrane, |

T.vesicolor>P.chrysoporium> |

Chibuike & Obiora33 |

|

kidney diseases, lung and nasal cancer, |

Decrease chlorophyll content |

inhibit enzyme activities, |

Pen sp.>Asp .sp .>Rhzsp |

Malik115 |

|

|

Zinc |

Ataxia, depression, gastrointestinal irritation, |

Reduced chlorophyll content |

inhibits growth |

P.chrysoporium>T.vesicolor>Rhzsp |

Gumpu et al.78 |

|

icterus, impotence, kidney and liver failure, |

impacts on plant growth |

Death, decrease in biomass, |

Asp .sp>Pen sp. |

||

|

Colbat |

T.vesicolor>P.chrysoporium>Asp . sp |

||||

|

>Pen sp.>Rhzsp |

|||||

|

Manganese |

oxidation of dopamine, resulting in free radicals, |

Plant growth affected and |

fitness of the organisms |

P.chrysoporium>T.vesicolor>Pen sp.> |

|

|

|

cytotoxicity nervous system (CNS) pathology |

poor quality yield |

damage to mitochondrial DNA |

>RhzspAsp .sp |

|

Table 7 Toxicity of heavy metals to life forms in Kachia, Kaduna, Nigeria

|

Fungi isolates species |

Explosives |

Conditions |

References |

|

|

Rhizopus spp. |

TNT |

TNT disappearances inmaltextract broth |

103 |

|

|

Electrophilic attack by microbial oxygenizes |

157 |

|||

|

Phanerochaetechrysosporium |

TNT |

Mineralization to Co2 by myceliumand /90% removal of TNT |

58, 152, 176 |

|

|

Mineralization to Co2 by spores |

169, 43, 47 |

|||

|

Mineralization to Co2 by mycelium |

126, 226 |

|||

|

Mineralization correlated with appearance ofperoxide activity |

172, 171, 176 |

|||

|

Mineralization to Co2 in soil corn cob culturesand stable |

214, 56 |

|||

|

Compost microbes |

TNT |

Biotransformation by thermophile microorganisms |

92, 88 |

|

|

Transformed ring [14c] labeled TNT humification reactions |

74, 21, 210 |

|||

|

Phanerochaetechrysosporium |

RDX |

Biotransformation under nitrate reducing |

62, 7 |

|

|

Reduction bynitrogen limiting conditions |

56, 58 |

|||

|

Reduction by sulfate reducing condition |

22, 23 |

|||

|

Methylene dinitramine formation under aerobic condition |

81, 102 |

|||

|

Aerobic denitration of RDXand highly mobile in soil |

61, 35, 6 |

|||

|

reduction under methanogenic conditions |

23, 224, 95 |

|||

|

RDX |

reduction lead to destabilization, ring cleavage |

122, 129 |

||

|

White rot fungus |

RDX |

Final products may include methanol and hydrazines |

83, 122 |

|

|

TNT |

Coagulation in contaminated water by nitrate reductase |

177, 20 |

||

|

TNT |

Treated TNT in wastewater and achieved 99% degradation |

226, 18 |

||

|

First step was degradation to OHADNT and ADNT |

5, 172, 171 |

|||

|

Aspergillus niger |

HMX |

Second step was to DANT including HMX and RDX |

12, 171 |

|

|

Sequential denitration chemical substitution |

188 |

|||

|

PETN |

Low water solubility in anaerobic conditions |

119, 120 |

||

|

Mineralization |

PETN |

Mono nitratedpentaerythrolto un nitrated pentaerythritol products |

209 |

|

|

Phanerochaetechrysosporium |

PETN |

Biodegraded by sequential denitration to pentaerythritol |

227, 17, 40 |

|

|

Nitroglycerin or glycerol trinitrate, degraded co metabolism |

206, 17, 174 |

|||

|

White rot fungus |

Explosives |

by sequential removal of nitro groups |

10, 11 |

|

|

Dissolution rates: TNT >HMX>RDX>PETN |

186, 25 |

|||

|

|

|

Degraders glycerol trinitrate and isosorbidedinitrate: nitrate esters |

207, 80 |

|

Table 8 Fungi Isolates Implicated in Biotransformation and Mineralization. Kachia, Kaduna, Nigeria

|

N/S |

Fungi isolate cultural |

Microscopic features |

Name of probable fungus |

References |

|

Appearance ( Visual) |

||||

|

1 |

Spores with dark, pigment, grey, or yellowish brown with sporaltion |

Sporongiosopres |

Rhizopus spp. |

103 |

|

Stingly, mycelia fuse and rhizoids |

||||

|

2 |

Black mycelium in long chains from the ends of the phialides |

Distinct Conidiophores |

Aspergillus niger |

96, 118, 121 |

|

3 |

Yellowish green to dark green hyphae |

Chain of conidia produced by phialides which are supported by branchedconiadiophores |

Penicillium spp |

116 |

|

4 |

Dark grey center with light gray periphery |

Scaphulariopsis |

T.vesicolor |

98 |

|

conidia pores bear annelids the produce chain of conidia |

||||

|

5 |

Spores wit dark, yellowish gray center with of blastoconidia |

terminal conidia is youngestand wasbudded from subterminal conidium |

Phanerochaetechrysosporium |

17, 175, 200 |

Table 9 Characteristics of Fungi Isolated from Twelve locations in NASA shooting range Kachia Kaduna

Another nitro-aromatic explosive used extensively for military octahydro-l,3,5,7-tetranitro-l,3,5,7-tetrazocine, also known as high melting explosive (HMX). shows no significant toxicological effects on soil microbes in concentrations as high as 12.5 g/kg of soil.72 Biodegradation of HMX occurs at a much slower rate than RDX due to the former's lower water solubility and higher chemical stability.Anaerobic bacteria capable of HMX degradation were isolated from a marine unexploded ordnance site. Sediments were first tested for their ability to remove spiked HMX and then predominant clusters of taxa were identified through 16SrRNA sequence alignment. HMX-degrading genera identified include Clostridiales, Paenibacillus, Tepidibacter and Desulfovibrio.219 Biodegradation of HMX occurs at a much slower rate than RDX due to the former's lower water solubility and higher chemical stability. Anaerobic bacteria capable of HMX degradation were isolated from a marine unexploded ordnance site. Sediments were first tested for their ability to remove spiked HMX and then predominant clusters of taxa were identified through 16SrRNA sequence alignment.

There are examples of microbes able to transform more than one of the principle explosives described above. For example, a photosymbiotic bacterium, Methylobacterium spp., isolated from poplar tissues and identified through 16SrRNA and 16S-23S sequence analysis, was shown to transform TNT and mineralize RDX and HMX in pure cultures.190 Due to the similar chemistries of RDX and HMX (both are non-aromatic, cyclic, nitramine derivatives), there are many instances in which a bacterial species is able to degrade both of these compounds.37 Examples of bacterial species able to catabolise both RDX and HMX include Morganella morganii B2, Citrobacter freundii NS2 Providencia rettgeri B1102 and several species of the genus Clostridium.218 In Figures 4&5 whose bioremediation potential observed in decreasing order were Bacillus subtillis, Enterobacter spp, E. coli, Arcobacter spp, Klebsiella pneumonia, Lysini bacillus and Achromobacter spp in the following order as (55.1%), (54.80%), (54.1%), (43%), (42.7%) , (37.8%) and, (31.5%)respectively. MBC showed high percentage degradation of explosive which might be attributed to the synergistic effect (HGT) between the catabolic enzymes in the eight bacteria isolates. These findings are similar to the result obtained by Duniya et al.,45 whose research reported biodegradation rates at 97% by MBC reported.143

Isolated bacteria species at the study site with potential for biodegradation of explosives are bacillus sp; Escherichia coli, Enterobacter sp, Klebsiella nitroreductases, Genes required for degradation of xenobiotic may be recruited by various horizontal transfer mechanisms 93 so that lateral gene transfer could be involved in the broad distribution of nitroreductases in prokaryotic organisms. Transmissible, plasmid-borne nitro-reductase genes have been reported in different bacteria146 and flanked by directly repeated sequences coding for putative oxygen-insensitive nitroreductases.116 It has also been hypothesized that the nitroreductase-like sequences present in the genomes of several protozoan species have been acquired by lateral gene transfer .116 These was the impacts of MBC at the polluted explosive biodegradation in Figures 4 and 5. Bacteria able to deal with these chemicals have a selective advantage and may survive in polluted environments. Escherichia coli NfsA and V. harveyi FRP group A nitro reductases, and the Escherichia coli NfsB, Enterobacter cloacae. The Klebsiella enzyme is able to reduce the ortho isomers to the corresponding hydroxylamino and amino derivatives. The Klebsiella enzyme is able to reduce the orthoisomers to the corresponding hydroxylamino and amino derivatives. Nitrosoarenes may react with the sulfhydryl groups, and cause protein inactivation.54 Binding of TNT to proteins also causes cytotoxic effects in the liver.110 Formation of haemoglobin adducts of TNT amino-derivatives has also been found in humans exposed to this explosive, and genotoxicity and potential carcinogenicity of TNT have been reported. Lactobacillus spp. reduction of TNT to TAT reported.49

The study site soil explosives treatment processes use two general approaches to bioremediation biostimulation and bioaugmentation. Biostimulation relies on altering external conditions such as temperature, mixing, nutrients (biofertilizer), pH, soil loading rates and oxygen transfer to favourable conditions for growth of native microbial populations. Bioaugmentation relies on these same factors to a lesser extent, and also relies on the use of additional inoculants with explosives biodegradation properties and in situ microbes (bacteria and fungi spices isolates) to increase the performance of the system. Inoculants usually employ cultures taken from other sites known to contain explosives-degrading microbial or fungal populations. The consequence is an increase in the mobility of parent explosives and intermediate compounds during biological treatment and co-metabolic degradation is optimum. The mixing soil explosives treatments will make results sustainable. In-situ biological technologies for explosives have many inherent difficulties due to heterogeneous concentrations in soil, and extremely low volatility.

Future work

Transgenic plants bearing bacterial nitroreductase genes, or combined treatments with both plants and micro-organisms able to degrade nitroaromatic compounds, are expected to be used as efficient decontaminating procedures in the near future called PC3R Technology an acronym for pollution construct remediation, restoration and reuse (treated pollutants materials/media)cum biodegradation monitoring with biosensors for sustainable development. PC3R Technology idea affirmed by scholars.64,78,79,106 Approaches for monitoring the bioremediation processesandtheir efficiency are also necessary.63–65 Biosensors based on living micro-organisms, enzymes or immunochemical reactions may also be developed to detect sites and materials polluted with nitroaromatic compounds.149 In addition, some efforts have been directed to develop new genetically modified bacterial strains able to degrade nitroaromatic compounds by hybrid pathways.45–117

None.

The authors declare that there was no conflict of interest.

Authors had no funding for this research.

©2020 Otaiku, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.