eISSN: 2574-9838

Research Article Volume 10 Issue 1

1Department of Psychiatry, Rutgers University, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, USA

2Center for Professional Studies, Timonium, Maryland, USA

3Department of Health Informatics, School of Health Professions, Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences, USA

4Department of Psychiatric Rehabilitation and Counseling Professions, Rutgers School of Health Professions, USA

Correspondence: Ralph L Piedmont, Center for Professional Studies, Timonium, Maryland USA

Received: December 23, 2024 | Published: January 13, 2025

Citation: Chatlos JC, Piedmont RL, Cooperman NA, et al. Pilot study of a CBT-based intervention for promoting spiritual experience among men in residential addiction treatment. Int Phys Med Rehab J. 2025;10(1):4-13. DOI: 10.15406/ipmrj.2025.10.00390

Objective: Previous studies claim a healing effect on psychological and medical symptoms beyond the biopsychosocial construct of medicine to include a “spiritual” aspect with added experience of wholeness and well-being. A recommendation for the development of a human ontological model for research of this spiritual domain has been suggested. The objective of this study was to test feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a non-psychedelic CBT-based psychotherapeutic intervention in men with long-term substance use and a history of incarceration as such a model.

Methods: Fifteen male residents of a long-term residential addiction treatment program received a 10-session manualized group psychotherapy intervention focused on opening experience to a spiritual level and providing emotional healing and greater well-being. Effects were measured with pre- and post-intervention psychological, healing, well-being and spiritual/mystical/ numinous assessments. The Intervention was done sequentially on two cohorts to assess replicability. Scales included ASPIRES (Assessment of Spirituality and Religious Sentiments Scale), NMI (Numinous Motivation Inventory), Hood Mysticism Scale, NIH-HEALS (NIH-Healing Experience of All Life Stressors Scale), WEMWBS (Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale).

Results: All scales’ Total scores showed statistically significant improvements post-intervention. The pattern and magnitude of change was similar for both treatment groups with 14 of 15 men self-reported a Very Strong (4 on scale of 1-5) or Extreme spiritual experience with this intervention.

Conclusions: This study demonstrated feasibility and preliminary efficacy of CBT-based model for a short-term group psychotherapeutic intervention to promote spiritual experience with emotional healing characteristics in men with addiction and post-incarceration in a residential treatment setting. Demonstration of this intervention, that impacts a spiritual level of experience, provides a foundation from which to study the extent of its abilities, compare with current treatments, and identify its unique healing elements. This study adds to the body of knowledge of identifying the role of spirituality in the biopsychosocial model of medicine. Results similar to studies with psychedelic medications suggest usefulness in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Inability to provide a control group limits specificity of results and determining the extent of efficacy and inclusion of only male participants with addiction and incarceration in a residential treatment program limits the scope of feasibility determination.

Keywords: CBT-STE, spiritual growth, addiction, incarceration, self-transcendence

Studies claim there is a healing effect on psychological and medical symptoms beyond the usual biopsychosocial construct of medicine1 to include a “spiritual” aspect with added experience of wholeness and well-being.2,3 This has become incorporated in SAMHSA’s major initiative for health and well-being4,5 identifying spirituality as a dimension of wellness. Spirituality is described as “an inner agency that gives a degree of relief from suffering, an inner agency that the patient must find within the depths of his or her own psyche”.2 While spiritual well-being is subjective, it can be described as encompassing “dimensions such as purpose, meaning of life, reliance on inner resources, and a sense of within person integration and connectedness”.6 In an extensive review by Koenig 3 most effects on health and mental health in these studies were related to religious practices, with spirituality usually not specifically included. Effects of religious communal participation have been shown to be much stronger than for spiritual-religious identity or for private practices.7 Recent research with psychedelics and mental well-being has highlighted the reality, nature, and value of spiritual/ mystical/ numinous experiences with its healing impact on multiple mental disorders including depression, anxiety, PTSD, OCD, and substance use disorders.8–13 Impact on these disorders is associated with spiritual/mystical experiences along with a sense of wholeness, well-being, and quality of life. Attempts have been made to explain psychologically these spiritual experiences and the effects of psychedelics,9,12,14 as well as the understanding and meaning of these experiences within the broader framework of naturalism and scientific materialism.15

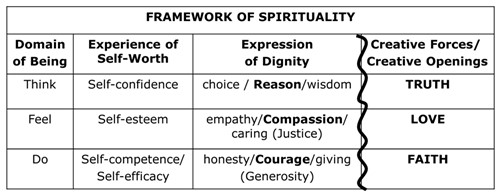

Attempts to comprehend spiritual experience outside of psychedelic studies have made significant progress. Piedmont et al,16 clarified and separated the two main constructs of religiousness and spirituality. It was demonstrated,17 that spiritual experience can apply to non-religious persons; can have unique effects beyond that from the Five Factor Model (FFM) personality traits of extraversion, neuroticism, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness; and proposed spirituality as a sixth factor of personality.18 A major NIH incentive developed the NIH-HEALS (Healing Experience of All Life Stressors) assessment specifically to measure this “psycho-social-spiritual healing” outcome.2 A review in Psychology of Religion and Spirituality outlined needs for a firm scientific grounding in exploration of spiritual experience.19 In response, Piedmont,20 called for developing an ontological model with “well-conducted empirical research….to demonstrate the unique causal role religious and spiritual / ‘numinous’ constructs have on psychological status of the individual.” This pilot study evaluates CBT-STE (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy-Self-Transcendent Experience) a CBT-based, manualized group psychotherapeutic 10 session intervention as a human research model as called for by Piedmont that intentionally promotes spiritual experience without psychedelic drug involvement. A value of CBT-STE is that it is based on a specific framework for understanding the psychological nature of spiritual /mystical/ numinous experience that is suitable for transdiagnostic treatment extending to the transpersonal (Figure 1).

Figure 1 This illustrates the theoretical Framework of Spirituality (FOS) beginning with the CBT elements of thoughts, feelings and behaviors, including the expansion to the distinction of self-worth, and the expression of dignity that expands socially as wisdom, justice, and generosity. The expansion to the Creative Forces/Creative Openings occurs as the spiritual core (??) is opened.

It provides a non-sectarian, non-religious language that is compatible with most known religious/faith traditions and secular settings. This makes it universally useful for therapy and counseling with people in various cultural and faith communities and for use in public institutions respecting separation of church and state. It also provides an empowering framework for integration with psychedelic treatments or for those persons unsuitable for psychedelic treatments. Additionally, the study sample chosen was men with repeated substance rehabilitation treatments followed by relapses and multiple incarcerations in jail or prison, with legal oversight through recovery court, probation or parole. Incarcerated men have a higher rate of co-occurring mental disorders and substance use disorders (12-15%) than in the general population (1.3%).21 This is an underserved population despite multiple evidence-based treatments and program models developed. Recent efforts have described success with a combination of CBT and mindfulness practices.22 As the intervention of CBT-STE includes both CBT and mindfulness elements and is designed for transdiagnostic use, this is an appropriately challenging population to test its feasibility of engagement and effectiveness. The study was intentionally limited to include only men as the intervention is very personal and the likelihood of intense emotions especially with male-female relationship issues including violence was believed to counter the limitations of choosing such a select group (see Discussion / Limitations). Any acts of violence related to the intervention would have ended the Study. All participants had post-incarceration legal oversight which may be a select population affecting motivation.

The program

The theoretical basis of this intervention is the Framework of Spirituality for understanding the nature of spiritual experience. This theoretical foundation has been described in various detail in relation to religion, spirituality and naturalism,23 adolescence and identity development,24 psychoanalytic/psychodynamic theory and practice25 and bullying, depression and anxiety.26 The group psychotherapeutic intervention was conducted by the first author an addiction psychiatrist with over 40 years experience in treatment settings and included three main components:

1) Attitude Change- identify and change attitudes that block openness to engagement, introspection, and connection; 2) Processing of Injury- to self-worth and dignity with memory recall, embodied emotions and decisions, with self-acceptance;

3) Opening to a New Life- adopt a spiritual attitude, discover meaning and purpose, moving forward in faith with courage. An outline of this specific intervention is in the Supplementary Material.

Hypotheses

As this is the first implementation of this model, a residential setting was chosen to minimize confounding variables of active or unknown substance use, poor compliance with attendance, and extreme external influences characteristic of this population. The study also examined the feasibility of the intervention by implementing the intervention twice, with two different cohorts in a sequential manner to both evaluate the replicability of the program and to rule out any confounds due to history effects. It was hypothesized that participants would experience significant increases in their levels of Spiritual Transcendence, Numinous engagement, and mysticism. Also, participants would exhibit significantly higher scores on overall personal well-being and factors related to healing, mindful engagement, and trust and acceptance. Additionally, it was hypothesized that these increases and rates of change over treatment would be the same for both groups, supporting the replicability of the intervention.

Participants

Participants consisted of 15 volunteers recruited from a long-term men’s residential addiction treatment program. Eligibility for the study included participation in the residential program for a minimum of the upcoming four months. Inclusion criteria included:

a) Being 21 years of age or older;

b) No psychotic, suicidal ideation, or psychiatric hospitalization in the past 3 months;

c) Able to pass MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) Exclusionary Criteria (as part of a related study).

Participants were recruited after viewing a presentation overview of the study intent and design followed by opportunity for questions. Participation in the study would have no impact on participation in the rest of their residential treatment, or on any legal status, and no information other than participation in the study was available to any legal oversight. Record review confirmed meeting study eligibility criteria. Informed Consent that met Institutional Review Board standards for inclusion of “Prisoners” as a vulnerable population occurred within one week of recruitment as a group at the residential site by study team members. Additionally, potential participants were offered an opportunity for private discussion and questions with a Coordinator. Participants received a $200 gift card upon discharge from the residential treatment program for completion of the study.

Demographic data were by self-report. Mean age was 40.43 years (range: 28 – 55). Participants were Black/African American (n=3), Caucasian (n=10), Hispanic (n=1), and Hispanic/Caucasian/American Indian (n=1); (n=1) had some high school education, no diploma received, (n=7) were high school graduates or GED, (n=5) had some college and (n=2) were college graduates. Marital status: (n=7) individuals had never been married, (n=3) were married, (n=4) were divorced and (n=1) was separated. Religious identification: None (n=3), Christian/non-Catholic (n=7), Catholic (n=3), Muslim (n=2). Participants that had three or more prior residential rehabilitation experiences, (n=8), had one or two, (n=5), or no previous experiences, (n=2). Total jail or prison confinement ranged from 1 day to 28 years with the average of 4.0 years: (n=5) participants had less than 3 years and (n=10) participants had 3 or more years. While the sample size is small, such sizes are not uncommon in clinical studies examining novel interventions, where client groups often range from 10 – 25 participants.27,28 Nonetheless, the sample does contain a relatively diverse range of people.

Measures

Assessment of spirituality and religious sentiments scale (ASPIRES): Developed by Piedmont,29 this 35-item measure of spirituality and religiosity of individuals is comprised of two main dimensions; a 23-item Spiritual Transcendence Scale (STS) which encompasses the three facets of Prayer Fulfillment (10-items, e.g., “I meditate and/or pray so that I can grow as a person”), Universality (7-items, e.g., “All life is interconnected”), and Connectedness (6-items, e.g., “Although dead, memories and thoughts of some of my relatives continue to influence my current life”). The STS items are scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5). There is also a total score that can be computed by aggregating the facet scales. Piedmont (2020) provides evidence of structural, content, construct, and predictive validity. Scales have been shown to be internally consistent (alphas are .95, .86, .60, and .93 for the Prayer Fulfillment, Universality, Connectedness, and Total Score, respectively). The second dimension is the 12-item Religious Sentiments Scale (RSS). The RSS is also multi-faceted and is comprised of an 8-item Religious Involvement (RI) scale and a 4-item Religious Crisis (RC) scale. The RSS is formatted similarly to the STS with the exception of the first three items which are on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from “never” (1) to “several times” (7).

Numinous motivation inventory (NMI): Developed by Piedmont30 this 22-item scale assesses numinous qualities of the individual. There are three facet scales: Infinitude (I), an intrinsic drive to acquire substance and continuity in one’s life in the face of one’s own mortality (item: I believe that this life is only one stage in a larger, eternal process); Meaning (M), captures the extent to which individuals have created an ultimate sense of personal meaning that they place their ultimate trust in and towards which they devote their lives (item: I am guided by my personal philosophy and/or faith); Worthiness (W), the extent to which individuals experience acceptance and worth, despite personal foibles and imperfections, from their perceived understanding of life (item: I value myself). Items are responded to on a 1 “Strongly Disagree” to 5 “Strongly Agree” Likert-type scale. Items are balanced to control for acquiescence effects.

Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): The Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale was funded by the Scottish Government National Program for Improving Mental Health and Well-being, commissioned by NHS Health Scotland, and developed by the University of Warwick and the University of Edinburgh.31 WEMWBS is a 14-item scale covering subjective wellbeing and psychological functioning, in which all items are worded positively and address aspects of positive mental health. The scale is scored by summing the response to each item answered on a 1 “none of the time” to 5 “all of the time” Likert scale. Scores derived from samples showed a single underlying factor, interpreted to be mental wellbeing, with low levels of social desirability bias and expected moderate correlations with other scales of wellbeing. Scores for individuals were stable over a one-week period. The normative mean score for this scale is 50.7 with an SD of 8.79. A clinically significant change is 3 or more points.

Healing experience of all life stressors scale (NIH-HEALS): Developed through the NIH by Ameli et al,2 this 35-item scale assesses important aspects of the degree of psycho-social-spiritual healing in the face of stressful or even life-threatening circumstances. Items are responded to on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree.” The scale assesses three dimensions: Connection which examines the extent to which someone is connected to family, a higher power, and a religious community (e.g., “My personal religious practice is important to me”); Reflection & Introspection assesses a sense of personal mindful engagement with life (e.g., “I want to make the most out of life”); and Trust & Acceptance captures a personal sense of personal contentment and levels of social support (e.g., “My friends provide support I need during difficult times”). The scale has demonstrated adequate reliability (Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale is 0.89) and evidence of construct validity. Normative information is presented for each scale and a total score based on responses from a sample of individuals with serious and life-threatening disease.

Mysticism scale: Developed by Hood,32 this 32-item scale is designed to assess an individual’s mystical experiences, characterized by a sense of unity with the outside world and/or with “nothingness,” which may or may not be interpreted religiously (e.g., “I have had an experience which was both timeless and spaceless”). While initially designed to capture Stace’s33 multicriteria for mystical experience, most uses of the instrument rely on a total score. Burris’34 (1999) review of the scale overviews the large validity literature that has accumulated for the instrument. Items are responded to on a 4-point scale from -2 “This description is definitely not true of my own experiences” to +2 “This description is definitely true of my own experiences." Normative information on the scale is based on samples taken mostly from religiously-oriented samples where mean overall scores range from 115 to 132; however, in more secular college samples scores hover between 105 and 110.

Spiritual experience assessment (SEA): Developed by the first author for this study, this scale contained six questions about participants’ experiences during treatment. The initial question “Would you say that during this study you have had what you would call a spiritual experience of any kind?” was followed by “If yes, how strong/powerful was the experience?” Participants then rated “Which of the following characteristics of spiritual experience were present for you?” included Connectedness, Aliveness/Energy/Power, Wholeness/Integrity, Serenity/Peace, and Meaning/Purpose. All responses were made on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 “none” to 5 “extremely strong.” The purpose of this measure was to determine how the intervention did or did not personally impact them spiritually.

Procedure

This study was conducted at a men’s long-term residential addiction treatment program in a mid-Atlantic state. This study was approved by the Rutgers University Institutional Review Board (Protocol #2022000889), supported by a pilot grant from the Brain Health Institute at Rutgers University and recorded in clinicaltrials.gov ID NCT05485181.

The study materials are not yet available as the data is still undergoing analysis. Two independent applications of the program were conducted in sequential order. Participants were assessed on study variables prior to their receiving the intervention. The CBT-STE intervention was then initiated and consisted of a 3-hour group introduction followed by 9 weekly 1½ hour group sessions aimed at promoting spiritual experiences. The second group required only 8 weekly sessions to complete the intervention as the intervention was designed with goals that were achieved earlier, rather than time-related content to be presented. The group sessions were video recorded for further manual development. At the conclusion of the program, participants were again assessed on the study variables. Each group was analyzed individually.The overview introduction was presented to 25 residents, out of which 20 volunteered. Of those volunteers, 1 left treatment before the consent, 2 refused to consent, 1 consented and refused to continue during the assessments, and 1 left treatment during the intervention leaving 15 participants that completed the study. During the intervention, there was full attendance except 1 missed a session due to illness, and 1 participant missed a session due to religious holiday.

The results of the interventions for the two groups are presented in Table 1. For Group 1, mean scores on the ASPIRES (specifically its Total Spiritual Transcendence Scale), the NMI, and the HEALS are given as T-scores having a mean of 50 and an SD of 10 based on normative data. Scores between 45 – 55 are considered average, while those above 55 are considered high and those below 45 deemed low. At pretreatment this sample is in the average range on the ASPIRES and NMI while the HEALS overall score is in the low range. The Mysticism Scale total score appears to be lower than values obtained in student and general population samples (which are usually >100). Finally, the WEMWBS scale of well-being is lower than normative average (which is 50.7). Overall, this pattern of scores indicates individuals who have some interest in ultimate existential issues, but are experiencing lower levels of personal well-being, a lack of inner peace and interpersonal trust, and a low level of mystical experiences in their lives.

|

Variables |

Pre-treatment |

Post-treatment |

F |

Partial Eta2 |

Power |

||

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

|

|

|

|

Group 1 (n = 8) |

|||||||

|

ASPIRES TotalB |

48.62 |

9.74 |

56.34 |

6.97 |

7.88* |

.53 |

.67 |

|

NMI TotalC |

47.95 |

8.96 |

57.12 |

5.69 |

6.99* |

.50 |

.62 |

|

HEALS TotalD |

42.19 |

10.92 |

51.47 |

8.43 |

23.62** |

.77 |

.99 |

|

Mysticism Total |

78.38 |

23.24 |

89.13 |

17.37 |

2.14 |

.23 |

.25 |

|

WEMWBS Total |

47.75 |

12.74 |

58.63 |

8.23 |

6.59* |

.49 |

.60 |

|

Group 2 (n = 7) |

|||||||

|

ASPIRES Total |

55.41 |

3.79 |

59.16 |

4.38 |

4.35a |

.42 |

.42 |

|

NMI Total |

50.47 |

6.39 |

58.46 |

6.07 |

7.19* |

.55 |

.61 |

|

HEALS Total |

50.59 |

5.68 |

59.73 |

6.23 |

8.81* |

.60 |

.70 |

|

Mysticism Total |

82.29 |

10.39 |

97.43 |

10.83 |

9.42* |

.61 |

.73 |

|

WEMWBS Total |

50.57 |

11.34 |

63.57 |

7.32 |

10.82* |

.64 |

.78 |

|

Combined Sample (N= 15) |

|||||||

|

ASPIRES Total |

51.79 |

8.12 |

57.66 |

5.88 |

11.69** |

.46 |

.89 |

|

NMI Total |

49.13 |

7.7 |

57.75 |

5.7 |

14.84** |

.52 |

.95 |

|

HEALS Total |

46.11 |

9.6 |

55.32 |

8.39 |

29.58*** |

.68 |

1.00 |

|

Mysticism Total |

80.2 |

17.9 |

93 |

14.81 |

8.36* |

.37 |

.77 |

|

WEMWBS Total |

49.07 |

11.76 |

60.93 |

7.96 |

17.63*** |

.56 |

.97 |

Table 1 Repeated measures analyses examining change over time for the treatment groups separately and together

a p < .08. * p< .05. ***p < .001.

BScores are T-scores having a Mean of 50 and SD of 10 based on normative data.17 CScores are T-scores having a Mean of 50 and SD of 10 based on normative data.30 DScores are T-scores having a Mean of 50 and SD of 10 based on data from Ameli, Sinaii, Luna, et al.2

Note ASPIRES, Assessment of Spirituality and Religious Sentiments Scale; NMI, Numinous Motivation Inventory; HEALS, Healing Experience of All Life Stressors scale; WEMWBS, Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale; Mysticism Total, Hood Mysticism Scale

For interpreting partial eta2 values; between .01 and .06 are considered small; between .06 and .14 are considered moderate; and values above .14 are considered large.

Five one-way repeated measures ANOVAS were conducted to determine whether changes in scores occurred over the intervention interval. In Table 1, there were significant improvements on four of the five scales (Mysticism did not significantly change). Scores on the NMI and ASPIRES moved into the high range, suggesting these individuals were much more engaged with existential issues and concerns and well-being scores climbed into a range associated with more personal fulfillment and life satisfaction. Scores on the HEALS indicated participants experienced increased levels of connection to family, a higher power, and community, with more mindfulness, and greater trust for others. Effect size estimates for these changes, partial η2, are consistently in the high range, indicating robust effects (i.e., low, medium, and large effects are denoted by values of .01, .06, and .14, respectively). Regarding the pre-treatment scores for the second group, overall, they indicated a more healthy and adaptive orientation (HEALS and WEMWBS scores were in the average range), although the overall Mysticism score was still below normative levels. Another set of five one-way repeated ANOVAs were conducted and four of the five scales significantly improved (scores on the ASPIRES exhibited a trend towards significance). Post-treatment scores indicated a very positive and psychologically healthy orientation towards life. Existential engagement was higher, well-being was normatively in the high range and Mysticism scores approached normative levels. As noted above, effect sizes for these changes were all in the high-range suggesting very strong and robust effects. There were small differences in mean levels between the two groups (e.g., group 2 appeared more adjusted than group 1) and the patterns of change were slightly different. To some extent, this variability can be attributed to the very small sample sizes of each group. It may also be possible that these two groups responded in different ways to the intervention, suggesting issues in both the content and application of the program. To examine whether the two groups evidenced comparable levels of change, a 2 (group 1 versus group 2) by 2 (pre- versus posttreatment) mixed model MANOVA was conducted. A significant main effect for time of assessment was obtained, Wilks Lambda = .25, multivariate F(5,9) = 5.34, p = .015, indicating that scores significantly increased over time for both groups. However, no significant effects were observed for group differences, Wilks Lambda = .53, multivariate F (5,9) = 1.63, p = ns and for the time by group interaction, Wilks Lambda = .88, multivariate F (5,9) = 0.25, p = ns. These findings indicate that there were no significant differences in scores on the outcome variables between the two groups and that the rate of change on these outcomes over time was also not different between the two groups, although overall both groups did significantly improve.

These findings support the aggregation of the two groups into a single, larger sample and the data re-analyzed to obtain more reliable estimates of change. First, a one-way, repeated measures MANOVA was conducted and a significant effect was obtained, Wilks Lambda = .01, multivariate F(5,10) = 5.97, p = .008. There were reliable changes in the outcome variables over the course of treatment. Second, five one-way, repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted to represent these effects, and the results are presented in row 3 in Table 1. As can be seen scores on all outcome variables were in the average range at pretreatment and at posttreatment all scores had significantly increased with most moving into the “high” interpretive range (Mysticism remained below the normative value of 100). Effect size estimates are all in the high range, indicating very strong change effects. Of particular note is the effect on general well-being as measured by the WEMWBS with a mean average change of 11.86 where a clinically significant change is 3 or more points. This is one of the most robust responses in the study.

To provide more details about what specific aspects of these constructs were changing, a series of dependent samples t-tests were conducted on the subscales of the ASPIRES, NMI, and HEALS scales. The results of these analyses are presented in Table 2. As can be seen, significant changes were noted on many of these more specific indicators. Given the small overall sample size utilized here, it is suggested that in evaluating these score changes a more conservative approach be taken. Thus, useful changes can be characterized by both a significant mean change but also an interpretive change as well. For example, on the ASPIRES, scores on both Prayer Fulfillment and Universality significantly increased (effect sizes are in the large range), but the post-treatment mean levels moved into the “high” range of scores based on normative data. Participants can now be considered strongly oriented to the presence of a larger, eternal reality and have embraced a more inclusive and unitive understanding of life. The NMI also indicated two significant increases, but only the Infinitude scale reflected scores moving from the average range to the high range, normatively. The effect size for this change (partial η2 = 1.03 is in the high range for the index). This finding supports results from the ASPIRES in that participants are taking a broader, more eternal time perspective in understanding their own lives.

|

Variables |

Pre-treatment |

Post-treatment |

t |

Cohens d |

||

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

|||

|

ASPIRESA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prayer Fulfillment |

51.08 |

10.28 |

57.29 |

6.52 |

-3.19** |

-0.82 |

|

Universality |

49.59 |

6.32 |

56.4 |

3.36 |

-4.99*** |

-1.29 |

|

Connectedness |

55.41 |

10.24 |

54.55 |

7.07 |

0.30 |

0.08 |

|

NMIB |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Infinitude |

51.84 |

7.86 |

58.31 |

5.74 |

-3.98*** |

-1.03 |

|

Worthiness |

46.18 |

10.48 |

54.55 |

5.8 |

-2.53* |

-0.65 |

|

Meaning |

50.52 |

7.18 |

52.83 |

8.02 |

-1.13 |

-0.29 |

|

Mysticism |

80.2 |

17.9 |

93 |

14.81 |

-2.89* |

-0.75 |

|

HEALSC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Connection |

48.81 |

8.54 |

54.05 |

6.23 |

-4.60*** |

-1.19 |

|

Reflection/Introspection |

43.73 |

7.6 |

50.78 |

7.24 |

-4.73*** |

-1.22 |

|

Trust & Acceptance |

41.34 |

9.6 |

51.39 |

10.01 |

-3.97*** |

-1.02 |

|

WEMWBS Total |

49.07 |

11.76 |

60.93 |

7.96 |

-4.20*** |

-1.08 |

Table 2 Correlated t-tests examining change over the treatment condition for both groups combined

N= 15. *p < .05. ** p < .01. ***p < .001, two-tailed

AScores are T-scores having a Mean of 50 and SD of 10 based on normative data.17 BScores are T-scores having a Mean of 50 and SD of 10 based on normative data.30 CScores are T-scores having a Mean of 50 and SD of 10 based on data from Ameli, Sinaii, Luna, et al.2

Note ASPIRES, Assessment of Spirituality and Religious Sentiments Scale; NMI, Numinous Motivation Inventory; HEALS, Healing Experience of All Life Stressors scale; WEMWBS, Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale; Mysticism Total, Hood Mysticism Scale

For interpreting Cohen’s d, values from .20 to .45 are considered small; values from .50 to .75 are considered moderate; and values of .80 and above are considered large.

Finally, scores on all three facets of the HEALS scale evidenced strong, significant changes over treatment. However, only the Reflection/Introspection and Trust & Acceptance scales changed interpretively, moving from the low range into average range. These interpretive shifts ought to be seen as representing truly substantive, meaningful change. One note of caution regarding the effect size estimates needs mentioning. While the current findings indicate a strong effect for the intervention, it needs to be considered that small samples naturally evidence larger effect sizes than more typically sized samples (e.g., N > 50). Nonetheless, significant clinical change may be best estimated by scale score changes that indicated shifts in interpretation from one normative category (e.g., average range) to another (e.g., high range).

Post-treatment spiritual experience assessment

All participants rated the strength of their experience on the Spiritual Experience Assessment scale and the results are presented in Table 3. As can be seen for all but one participant (1-02) everyone rated the program as generating a very strong impact on them across all of the spiritual dimensions reflected in the scale. Ratings are all in the 4-to-5-point range, representing very strong to extremely strong personal impacts. Comments by all participants indicate new, emerging feelings of centeredness, emotional balance, deeper interpersonal connections, and a general sense of overall emotional wellbeing.

|

Participant |

Strength |

C |

A/E |

W/I |

S/P |

M/P |

Comments |

|

1-01 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

Hard to explain but I just feel stronger mentally and my connectedness with spirituality is a lot stronger. |

|

1-02 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

Empathy, I connected to people and related to feelings of loss, hurt, pain, loneliness, and a sense of want or need. |

|

1-03 |

4 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

The term synchronicity was explained to me. I had a synchronicity occur at which point my hairs on my arms stood up. I had goose bumps and felt a total body vibration/quiver-like sensation. This feeling was a good one where I felt as one with the universe. |

|

1-04 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

3 |

5 |

My entire look on life changed. I now feel like I’m here for a reason and I have the potential to do everything I need to do. |

|

1-05 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

thoughts of calm, understanding, acceptance |

|

1-06 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

Since this group I have had the thought that this experience was a spiritual awakening of sorts. I’ve felt more connected/spiritual and made a lot of progress in spiritual strength and my recovery. |

|

1-07 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

At first everything starts to go very fast heart rate, breathing, etc. Then I pray and suddenly I get a warm calming feeling followed by goose bumps, my heart slows down, my breathing goes back to normal and it’s like all the weight I carried is gone. |

|

1-08 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

When I opened up about my dramatic situation, my main thought was fear of saying it, my feeling was numbness and my body sensation was a high level of alertness. |

|

2-02 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

Everything I’ve been reading... praying about, group discussions (in and out of this study) has been aligning and has been really making sense to me. God has been disclosing this in a big way for me. |

|

2-03 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

I have been feeling closer to everything around me. I am seeing clearer in all aspects of love. I can’t wait to get back to reality! |

|

2-06 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

I would get chills every time I connected with someone or when simple coincidence happened especially because I don’t believe in coincidences. I have felt feelings I’ve never felt before and can connect on a whole new level. |

|

2-07 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

I got the purpose that I was looking for. |

|

2-08 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

less chatter in my mind, feel lighter/weight off my shoulders, goose bumps |

|

2-09 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

4 |

2 |

I learned that God will be there for me through everything. Also that we are all connected and can help each other as long as we stay open-minded, open-handed, and open-hearted. |

|

2-10 |

5 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

I believe I have a purpose in life now. I have finally found peace within. I no longer am afraid of myself. I have this aliveness and burst of energy like I’m ready for whatever comes my way because I have this faith and my connection with my higher power that’s absolutely incredible. |

Table 3 Self-reported responses to group intervention

Strength, strength of spiritual experience; C, connectedness A/E-aliveness/energy; W/I, wholeness/integrity; S/P, serenity/peace; M/P, meaning/purpose

Note Self-reported responses to group intervention. All scores from 1- minimal to 5-Extreme

The results of this feasibility study to assess preliminary efficacy of a CBT-based intervention for promoting spiritual growth provide support that CBT-STE can feasibly be implemented for use with men with long-term substance use and post-incarceration. Overall, even in this challenging population, participants experienced significant gains in efficacy as determined by spiritual transcendence, existential life engagement, well-being, spirituality, and healing effects. The effect sizes for these gains were in the large range (mean parital η2 = .52) and most of the score changes indicated interpretive changes as well (e.g., scores going from normatively average to high). The effect sizes observed here compare favorably with other studies using the Unified Protocol that is described later28 using a sample of 15 participants found mean effect sizes (η2) on their primary psychological variables of .35 and .37 for their Study 1 and Study 2 outcomes, respectively). The noted participant’s comments indicated a sense of change that reflected a more holistic shift in how the person engaged with life. This change reflected more than just the acquisition of specific, task-related skills acquisitions, but a lifestyle shift that enables a more satisfying and engaging way of life. Conducting the intervention twice with independent groups provided an opportunity to examine the replicability of the intervention twice with independent groups demonstrated the replicability of the intervention. Recognizing that this was not a fully powered study, analyses suggested that both groups changed significantly and in similar ways providing evidence for the hypothesis that the intervention generated similar effects in both groups. Thus, the small observed differences in scores between the two groups most likely represented mere sampling error. The high effect sizes support the conclusion that these personal changes were not random improvements.

Feasibility

This study demonstrated feasibility and potential promise of CBT-STE as an ontological (the study of being human including meaning) human research model for promotion of spiritual / numinous experience in a non-drug facilitated intervention. Yet, these findings have important implications for substance abuse treatments that employ psychedelics. Studies leading to the pursuit of FDA approvals for psychedelic treatments have only occurred for psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (PAP) and not just for the approval of psychedelic use alone.35 The administration of mind-altering drugs is done in an effort to promote and enhance the efficacy of an underlying treatment modality. Processing of these psychedelic-induced experiences has relied on manuals describing various therapies,36,37 including non-directive supportive, CBT,38 combined CBT and MI (Motivational Interviewing),39 Internal Family Systems Therapy (IFST),40 Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) which includes Mindfulness Meditation,41,42 and others.35 The type of assisted therapy to be used with psychedelics has become important with an international effort to begin providing guidelines.37 Many of these approaches use a CBT framework, the standard of care for mental health treatment,43 with focus on the psychological perspective of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors related to events and memories of the participant. Given the demonstrated value of the treatment approach evaluated here, the results of this study raise some important, major questions about PAP including:

1) To what degree is the experience of the psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy sessions directly medication related;

2) To what degree is the experience integrated with life experience;

3) To what degree does the drug induced experience address more than symptomatic relief;44

4) Given the great amount of time to prepare clients and administer the psychedelic protocol (i.e., extensive clinical intervention is required per participant, ranging from the minimum of 6 hours per drug session up to 20+ hours with pre-drug preparation, post-drug integration and an additional 6-8 hours of 1-2 drug use sessions), can a brief, focused intervention like the one here provide a more efficient, yet equally effective, intervention?

Of note, the Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ) used in psychedelic studies45 and designed for individual discrete mystical experiences with classic hallucinogens, is derived from the Hood Mysticism Scale used in this study that uses language focused on lifetime experiences. The Mysticism Scale was chosen over the MEQ as it allows assessment of participants’ prior experience since most have been in recovery programs with a spiritual focus (i.e., 12-Step). Our investigation used a comparison of before and after intervention to evaluate whether a moderate time-frame (1-2 months) result can be identified. Results of our findings showed that both groups had below average mystical experiences prior to the intervention. The combined group revealed a small significant change post-intervention. This is likely to be an undervalue explained by the large variance with the Hood Mysticism Scale of Group 1 participants with a pre-intervention SD of 23.24 and a post-intervention SD of 17.37 while Group 2 had an average pre- and post- intervention SD of about 10. Further study of CBT-STE would benefit from a modified questionnaire using aspects of both scales to capture recent (1-2 months) but not acutely discrete experiences.

Comparison to other psychotherapy interventions

This use of CBT-STE in the successful promotion of similar spiritual/numinous/mystical experiences and overall well-being as in PAP suggest that this intervention may potentially provide similar results as PAP (requiring head-to-head studies) or at least be considered as a preferred therapy method for PAP. This would also require further comparison studies. It should also be considered for populations that are not desiring psychedelic treatments or are not suitable for such treatments. Additionally, its efficiency of facilitator time in a group setting (8 people with 15 hours of facilitator time) should encourage study comparisons with psychedelic treatments for broad dissemination. It is noteworthy that when compared to the Unified Protocol (UP), an evidence-based trans-diagnostic CBT related intervention46,47 the CBT-STE included almost all of the specific elements of the within this intervention. These include skills of mindful awareness, emotional management, cognitive flexibility, physical body awareness, and aversive memory exposure. The UP has been primarily developed for internalizing disorders and is theoretically related to neuroticism/negative affect. Suggested future directions of UP46 include having more focus on positive traits and temperaments. There were no direct measures of positive affect in this study but this may have been captured with increases in the NMI Worthiness and NIH-HEALS Trust & Acceptance scales.

CBT-STE provides two additional elements not included in the UP- the focus on the integrated experience and role of attitudes, and the process of making and empowering distinctions of self-worth and dignity. As attitudes include more than behaviors, this intervention goes beyond just skills at managing affect or aversive reactivity. The inclusion of distinctions of self-worth (integration of self-confidence, self-esteem, and self-competence/efficacy) and dignity (integration of reason, compassion, and courage) are believed to be critical to the success and holistic approach of CBT-STE, as distinctions are integrated experiences of being. For instance, the distinction of “balance” includes a thought of “I’m not falling,” a feeling of usually exhilaration and fear, and the actual act of balancing. Once a distinction has been made, it is embodied in experiential memory as noted when a person rides a bicycle after 20 years of not riding. A clinically relevant example of this is Major Depressive Disorder in which the injury to self-worth and dignity are associated with shame and guilt. This is associated with low self-esteem and low self-confidence with insecurity and anxiety, anhedonia as the limitation of empathy and compassion, indecisiveness affecting choices with reason, and fearfulness and social withdrawal demonstrating lack of courage and wanting to hide and literally not wanting to be honest, exposed or authentic with their self and the world. There are additional elements of enhancement of positive functioning included in CBT-STE as suggested by Barlow and Long. This occurs with the focus on increased agency from increased self-efficacy (part of self-worth), making choices with reason (part of dignity), gratitude and forgiveness as part of processing injury to self-worth and dignity, and a loving acceptance with self-compassion which leads to hope. In this process, hope which is future-oriented and may be symptom reducing is powerfully transformed to faith as an action. Faith as an action may come from or bypass hope, is in the here and now taking a courageous leap into an unknown future and may be the moment of awakening of the creative spirit and the core of spiritual experience. This is well-described by the philosopher theologian Paul Tillich: “Courage...transcending the non-being of the anxiety of fate and death...the anxiety of emptiness and meaninglessness (and) …the anxiety of guilt and condemnation... has the character of faith.”48 (p.155)

Note that these are the key elements of the NMI - Infinitude, Meaning and Worthiness scales.30 The theoretical position of the Framework of Spirituality is that the shared causal mechanism for participants’ suffering and poor function is injury to a person’s development of self-worth, dignity and the creative forces. This injury leads to maladaptive behaviors and may lead to a temperament of neuroticism with the development of negative or aversive reactivity that benefits from an intervention that reaches the levels of transcendent love and connectedness, moral truth, and faith for its “soul” and “spirit” healing effect. As such, CBT-STE is suitable for addressing both internalizing and externalizing disorders as described by Chatlos26 in relation to the impact of bullying which was prevalent in almost all of the study participants and is related to loss of faith in self, others, and the world. Processing of their previous criminal behaviors and harmful actions during their active addiction uncovered evidence of a moral core out of their awareness that experienced injury despite continued “immoral” behaviors. This has been previously identified within work on moral injury and dignity.49 Men that were now out of prison experienced how they were able to now let the prison of trauma out of the man for a new freedom and salvation.

Ontological model

As called for by Park and Paloutzian19 and Piedmont,20 CBT-STE is an ontological model with firm scientific grounding. It describes, explores, and clinically uses the manner in which spiritual experience is organized within our human experience. Further, CBT-STE has a robust impact on general well-being as evidenced by the large effect size of the WEMWBS measure. The significant impact of the program on all 3 factors of the NIH-HEALS suggests that it taps into the specific construct of the importance of mindfulness and resilience which were part of the intervention that may contribute to a “holistic psycho-social-spiritual healing of mind, body and spirit”.2 Its inclusion of skills and focus in the here-and-now with a more holistic and embodied focus on the mind, heart and body make it compatible with embodiment practices which integrate these factors such as holotropic breath work,50 Reiki,51 and integrated body practices such as yoga, Tai Chi, and Qi Gong as well as many aspects of Gestalt therapies.52,53

Challenges to biopsychosocial model

The current challenges to psychiatry and the biopsychosocial medical model may be addressed with this holistic model. Movement from a disorder focus to a symptomatic focus resulting from injury to the basic experience of thoughts, feelings and behaviors as well as the injury to self-worth, dignity, and the creative forces provides a strong foundation for development of a practical biopsychosocial-spiritual model.25 This ontological drive toward fulfillment of the capacity for self-worth and dignity suggest that this spiritual core is a holotropic system (moving toward wholeness).50 Opening of this core is associated with mystical/numinous experiences and has innate healing properties similar to the automatic healing properties of our physical body, or the automatic healing properties of our emotions such as the healing of a “broken heart” that can occur following grief from a death or the loss of a relationship. The extent to which this has influence over the physical body contributing to healing of medical conditions is yet to be studied especially considering the role of poly-vagal influences on the physical body.51 As previously noted, much literature has detailed the improved health and well-being outcomes of people involved in religious practices with research often not separating spirituality and non-religious but spiritual practices.. The CBT-STE clarification and operationalizing of spiritual experience may explain some of the benefits of religious experience and practices with health promotion, and further studies will be needed to determine if it provides additional benefit. These considerations suggest that self-worth and dignity and spirituality as a source of healing must be considered as more central to medicine and psychiatry and assist in developing a practical biopsychosocial-spiritual model for medicine.

Spiritual core (??)

Results of this study along with observations of the facilitator of these groups suggests that humans have what can be referred to as a spiritual core. It is suggested that this be symbolically designated with the Greek symbol ?? (sigma) as details about it are yet unknown and it refers to an “added” level of awareness. The symbol ?? has no historical or personal connotations as the words spiritual, mystical and numinous. The use of a symbolic designation is suggested to connect it with and separate it from other studies of human consciousness in which ?? (phi) is the measure of consciousness,55 ?? (psi) refers to psychic phenomena,56 and ?? (omega) refers to the pinnacle of human striving.57 Psychedelic related research pursues how this spiritual core is a functional part of the brain that may be localizable as a connect ome or even as often suggested, the Default Mode Network (DMN).9 Within this spiritual core is believed to be a functional capacity for experience of self-worth and dignity. As self-worth is developmental,58 behaviors related to self-competence begin ages 1-2, emotions related to self-esteem occur ages 3-4, thoughts of self-confidence occur with the ages 5-8 associated with increased myelination, with the capacity for the integrated experience of self-worth occurring about ages 8-10. As dignity is the capacity that matures during adolescence, the impact of puberty with hormonal, body and brain changes, expanded emotional experience including mature sexuality, and extended social relationships beyond the family may be the foundation for the development of increased reason, compassion and courage respectively.

Partial evidence of this functional capacity theory is the capacity for abstract thought/reason that develops during adolescence. This is a capacity that is present and only about 50% of adults actually fulfill or develop this capacity, dependent on environmental promotion. The Framework of Spirituality postulates that there are functional aspects of our brain that embody the other capacities of dignity - compassion and courage – that also require environmental promotion. A useful image of dignity is a three-legged stool. Basing our efforts at human flourishing on reason is like standing the stool on one leg – it can move in any direction as it falls. Addition of compassion allows the stool to stand on two legs, now with only 2 directions to move as it falls. Addition of courage as it tightly integrates with reason and compassion now has three legs of the stool to hold the weight of human flourishing and does not fall. Reason without compassion is heartless, compassion without reason is directionless, and reason and compassion without courage is feckless.

The final discussion involves the interpretation of this study and the understanding of the FOS and ?? in the challenge currently present against naturalism and scientific materialism. The occurrence of mystical experiences due to a new awareness often invokes explanations of magic, supernatural, various unidentified energies, miracles, quantum entanglement, contact with another realm or universe, and/or presence of an external cosmic consciousness. These interpretations must first meet the challenge of materialist explanations as ?? is a reality in the natural world and can explain many of the non-ordinary phenomena identified for study by the EPRC (Emergent Phenomena Research Consortium https://theeprc.org/publications). The presence of ?? must be considered in future consciousness studies and theological explanations of the human condition in the universe.

While this study was a first effort at examining the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of this new treatment approach, there are six limitations to this study that need to be outlined. First, the major limitation of this study was the lack of a no treatment control group. Inclusion of a control group would have ruled out the effect of the residential program itself as well as controlling for history and expectation effects among participants. Second, the small sample size necessitates caution in the interpretation of the effect size results. While the data did have sufficient power for the parametric analyses and the consistent findings of significance underscore the robustness of the observed effects (no doubt a consequence of the use of psychometrically sound scales), the effect size estimates need to be viewed with caution. Small samples do naturally generate large effects. The effect size estimates need to be replicated and examined in larger samples where it is most likely that more moderate sized effects will be observed. Third, these results cannot be generalized to other treatment settings or populations given the small and homogenous sample used. The use of only male residents provide no information about the impact on women or even on a mixed male-female group. Also, due to the intimate nature of experiences processed, including sexual and physical violence, extreme caution is advised in applying this to mixed male-female groups. Fourth, the facilitator was male which may have had an unknown impact of treatment efficacy and the need exists to determine how therapist gender impacts client responsiveness, especially with regard to the discussion of sexual/physical violence. Fifth, the small sample size precluded any examination of covariates that may have influenced outcome. Future research may want to directly examine the role of age and type of substance use as potential covariates. Finally, The Spiritual Experience Assessment scale was author generated with no data for validity or reliability. Moving forward, the use of larger, mixed-gender groups being conducted by mixed-gender therapists would be helpful. Larger samples, including more typical substance abuser profiles would help in the generalizability of the findings. Of course, including no-treatment control groups would help rule out other potential confounds. While one strength of this study was the inclusion of well-validated scales (except the SEA), future research ought to include mixed-method designs that can help identify the idiographic impact of the treatment.

As this is only a pilot feasibility study, research is needed to pursue questions of validity, reliability, comparison with evidence-based treatments, comparison with psychedelic and other interventions, and inclusion with psychedelic interventions. Its short-term manualized design makes it a good research model for these studies as well as studies to directly explore the nature of spiritual /mystical/numinous experience with electrophysiological monitoring, neuro-imaging such as fMRI, and further psychological assessments. It is hoped that laboratories with studies in these areas will pursue further research with this model.

Kasia Bieszczad as Co-PI, assisting in securing funding and protocol development; Anna Konova and Keith Stowell as Co- Investigators in development of the protocol; Damon House Board of Trustees and Jackie Weist and Annie Russo for providing and managing study site; Thanusha Puvananayagam for coordinator and data management.

Dr. Piedmont received royalties on the sale of the ASPIRES and NMI scales

©2025 Chatlos, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.