International Journal of

eISSN: 2574-9889

Case Report Volume 11 Issue 2

Department of anesthesiology, Mid & South Essex NHS Foundation Trust, Basildon University Hospital, UK

Correspondence: Reda El Bayoumy, MD FRCA, Department of anesthesiology, Mid & South Essex NHS Foundation Trust, Basildon University Hospital, UK

Received: May 26, 2025 | Published: June 6, 2025

Citation: Bayoumy RE. Iatrogenic malignant hyperthermia during cesarean section. Pregnancy & Child Birth. 2025;11(1):32-34. DOI: 10.15406/ipcb.2025.11.00318

Malignant hyperthermia (MH), also called malignant hyperpyrexia, is a potentially lethal syndrome and is a rare genetic condition that runs in some families.1 The underlying genetic susceptibility is most often due to a range of autosomal-dominant mutations in RYR1. In people who are susceptible, some anesthetic drugs and gases can cause a rapid rise in body temperature. Susceptible means that the people who have variations of certain genes are at higher risk of having a reaction to some anesthetics. Malignant hyperthermia is usually triggered by inhalation anesthetics or succinylcholine (suxamethonium).1,2 During the reaction, an increase in metabolic rate driven by an increase in intracellular calcium levels in muscle. Presents with increased carbon dioxide production, muscle rigidity, tachycardia, hyperthermia, and mixed metabolic and respiratory acidosis. Rhabdomyolysis, acute kidney injury, hyperkaliemia, and disseminated intravascular coagulation are frequently seen.1,2 The former is called primary or idiopathic MH, however there is as well the secondary or iatrogenic MH which is caused by other causes rather than a genetic condition & exposure to anesthetics. Causes of iatrogenic hyperthermia include infections, sepsis, immune-mediated disorders, neoplasia, administration of drugs that uncouple oxidative phosphorylation, and endocrinopathies.3

Keywords: malignant hyperthermia, sepsis, intravenous prostaglandin

MH, Malignant hyperthermia; PG, Prostaglandin; ABG, Arterial blood gases; BMI, Body mass index; GCS, Glasgow coma scale; LSCS, Lower segment cesarean section; WBCs, White blood cells; RBC, Red blood cell; CRP, C-Reactive proteins; kg: Kilogram; C: Celsius; ET, endotracheal; ICU, Intensive care unit; IV, Intravenous; CO2, Carbon dioxide

A 38-year-old primigravida at 34 weeks of gestation, with no significant past medical history, presented to our hospital with a low-grade fever (37.8°C) and general malaise. She was admitted to the maternity unit for further evaluation.

On presentation, the patient was hypotensive and tachycardic. Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis revealed severe metabolic acidosis with a base deficit of -13 and an elevated lactate level of 9.2 mmol/L. Her weight was 87.3 kg, corresponding to a BMI of 29.6. She was oliguric, tachypneic, and confused, with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 13.

Laboratory investigations showed leukocytosis (WBC count: 23,000/mm³), elevated C-reactive protein (CRP: 276 mg/L), and a procalcitonin level of 4.3 ng/mL. She was carrying monochorionic, diamniotic identical twins, and her prenatal course had been uneventful with appropriate antenatal follow-up.

Obstetric examination revealed live fetuses, but cardiotocography showed paroxysmal decelerations. The consultant obstetrician opted for an urgent cesarean section, classified as Category B. Coagulation parameters were within normal limits, though the patient exhibited hyperfibrinogenemia.

After fluid resuscitation to stabilize blood pressure, spinal anesthesia was safely performed. The anesthetist administered 2.2 ml of 0.5% heavy bupivacaine combined with 5 µg of sufentanil, achieving a bilateral T6 sensory block. The patient responded well to fluid management, with improvements in consciousness, tachycardia, urine output, and lactate levels.

Prophylactic antibiotics were initiated with 4.5 g of intravenous Tazocin and 480 mg of Gentamicin. The twins were delivered within 5 minutes of skin incision. Both neonates were floppy, with an APGAR score of 5 (scored 1 at each interval), and were intubated by the attending pediatrician and transferred to the neonatal ICU.

The mother remained hemodynamically stable; however, the uterus was atonic. The obstetrician initiated uterine massage with warm swabs. As per local protocol, the anesthetist administered 10 IU of intravenous oxytocin, followed by an infusion of 30 IU diluted in 250 ml of normal saline at 125 ml/hour. Despite this, uterine tone did not improve. An additional 10 IU of IV oxytocin was given, without response.

The obstetrician requested intravenous prostaglandin E2 (misoprostol), but the anesthetist declined due to the patient’s febrile status (37.6°C), citing the contraindication of prostaglandins in the context of possible sepsis. The obstetrician opposed proceeding to hysterectomy, citing the patient’s age and prior refusal. The anesthetist proposed intramyometrial misoprostol injection, which was not authorized under French guidelines.

Eventually, after stabilization, the anesthetist agreed to administer intravenous misoprostol per national guidelines. Uterine tone improved rapidly post-administration; however, the patient became agitated, restless, and confused. Her body temperature escalated sharply to 48°C within minutes, and her GCS dropped to 9. Despite worsening tachycardia, she remained hemodynamically stable.

The anesthetist immediately summoned the ICU consultant. They jointly induced rapid-sequence intubation using 50 mg IV ketamine, 20 mg IV etomidate, and 100 mg IV rocuronium. Endotracheal intubation was uneventful. The patient was sedated with dexmedetomidine and sufentanil infusions, and invasive monitoring was initiated. Bispectral Index (BIS) monitoring guided anesthetic depth. Fluids and phenylephrine infusion were used to support blood pressure.

Despite sedation and intubation, the patient’s core temperature continued to rise, reaching 49°C. Suspecting malignant hyperthermia, the anesthetic team administered 2 mg/kg IV dantrolene. Her temperature normalized within minutes, and she remained hemodynamically stable. Laboratory results revealed elevated serum creatine kinase and potassium levels, with brown-colored urine indicating myoglobinuria.

Postoperatively, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). Blood cultures from both the mother and twins revealed *Klebsiella* sepsis. Appropriate antibiotics were administered. The patient was successfully extubated on day 7 without complications.

Mother and twins were discharged in good condition on day 27, with no residual issues.

Primary MH is thought to be a dose-dependent event dictated by interindividual variability, its incidence ranges between 1:10,000 and 1:250,000.1,2 Children and young adults are especially at risk, with children under 15 years of age accounting for over half of all cases. Further, the mean age of MH patients is 18.3 years. 1,2 Overall, males are more often affected than females, as are those with a muscular body build. All races are equally susceptible worldwide. 1,2 Clinical signs of MH can develop within few minutes to several hours after a triggering event. 1,2 The most common signs are tachycardia, high end-expired CO2 partial pressure, hyperthermia, severe metabolic acidosis, and marked increases in serum magnesium, phosphorus, calcium, and potassium concentrations. 1,2 A presumptive diagnosis of MH can be made in part, on the basis of a familial history of hyperthermia episodes triggered by anesthetic agent. Definitive diagnosis is based on results of various tests, including the muscle contracture test, determination of RBC fragility, the halothane-succinylcholine challenge exposure test, and DNA testing. Causes of iatrogenic malignant hyperthermia include infections, sepsis, immune-mediated disorders, neoplasia, administration of drugs that uncouple oxidative phosphorylation, and endocrinopathies. There is no available epidemiological data & the clinical picture mimics those of idiopathic malignant hyperthermia.1–3

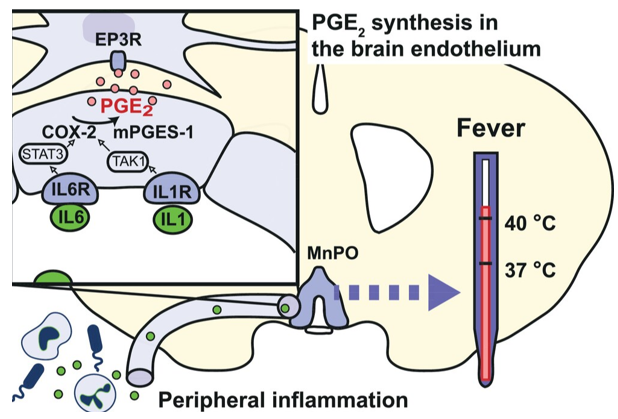

Prostaglandin E2 as a mediator of fever: Prostaglandin (PG) E2 production in brain endothelial cells has a critical role in generating fever.4,5 Although both peripheral and central cytokine production may contribute to fever, the critical mechanism is PGE2 synthesis and its binding to EP3 receptor expressing neurons in the median preoptic nucleus (MnPO) of the hypothalamus.4,5 If PGE2 synthesis is blocked or EP3 receptors are deleted in the MnPO, no fever occurs, even though there still is increased cytokine production in the periphery and in the brain. The critical PGE2 synthesis occurs in brain endothelial cells as shown by the absence of fever when the PGE2 synthesizing enzymes cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox-2) and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 (mPGES-1) are deleted from these cells.5,6 Cox-2 and mPGES-1 are in turn induced by cytokine binding to receptors on the endothelial cells (Figure 1). If these receptors, such as those for IL-1 and IL-6, or their downstream signaling molecules are selectively deleted from brain endothelial cells, the fever is suppressed (Table 1).4–6

Figure 1 IL-1 and IL-6 elicit PGE2 synthesis in brain endothelial cells via IL-1 receptor type 1 (IL1R) and IL-6 receptor α (IL6R) and Tak1/NfκB and STAT3 signaling, respectively. The PGE2 binds to receptors on thermoregulatory neurons in the median preoptic nucleus (MnPO).5

|

Presentation |

Noteworthy lab values |

|

Increase in end-tidal CO2 levels |

Respiratory / metabolic acidosis |

|

Tachypnea |

Elevated serum potassium |

|

Tachycardia |

Elevated creatine kinase |

|

Dysrhythmia |

Myoglobinuria |

|

Rise in body temperature |

|

|

Muscle rigidity |

|

|

Rhabdomyolysis |

|

|

Acute renal failure |

|

|

Disseminated intravascular coagulation |

|

Table 1 Key clinical features of malignant hyperthermia

Treatment in the case of a suspected episode of MH, all triggering agents should immediately be withheld and surgery rapidly aborted; if surgery must be continued, intravenous anesthetics and non-depolarizing muscle relaxants can be used. Hyperventilation, cooling of the patient, and administration of dantrolene, an RYR1 antagonist, should occur concurrently.2,3 Dantrolene should be given at a dose of 2–2.5 mg/kg every five minutes until the patient stabilizes. If more than 10–20 mg/kg of dantrolene is given in total with no improvement, a diagnosis of MH should be reconsidered. 2,3 Hyperkalemia and arrhythmia can be treated with standard medications. However, it is crucial to avoid calcium channel blockers, as these will result in cardiac arrest in combination with dantrolene.2,3 It is recommended that blood gas analysis, blood glucose, electrolyte, lactate, creatine kinase, urine and blood myoglobin, and coagulation studies be evaluated at the onset of MH and repeated at 30 min, 4 h, 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h. If dantrolene is not readily accessible, successful management of MH may be possible via alternative means. Measures such as dopamine, dobutamine, hydrocortisone, heparin, and furosemide administration, in addition to other supporting therapies such as magnesium sulfate. Fluid challenge should be administered IV to lower the body temperature and to improve kidney functions and prevent myoglobin-induced renal failure. Additional cooling measures can include placement of ice packs around the large superficial blood vessels of the body and administration of cold water lavages and enemas.7–9 Recrudescence of MH may also be possible, in which signs of the disorder return after proper treatment of an initial MH episode.10–12 Approximately 20–25% of patients will experience a recrudescent event, therefore, patient should be admitted to ICU immediately (Table 2).2,3

|

Eliminate the agent |

|

Give 100% oxygen at maximum flow Hyperventilate |

|

Administer dantrolene sodium 2.5 mg/kg IV, then 1 mg/kg every 4 to 6 hours |

|

Commence active body cooling |

|

Cool water blankets |

|

Refrigerated 20 mL/kg IV fluid |

|

Symptom |

Treatment |

|

Hyperthermia |

Cold intravenous fluids: 2-3 L 0.9% NaCl4°C |

|

Ice packs placed over the neck, groin and axillae |

|

|

Gastric, bladder and rectal lavage with cold fluids |

|

|

Therapeutic hypothermia |

|

|

Cessation of cooling at core temperature of < 38,5°C |

|

|

Hyperkalaemia |

Infusion of glucose with insulin |

|

Intravenous CaCl 10mg / kg |

|

|

Dialysis or continuous renal replacement therapy |

|

|

Arrhythmias |

Intravenous Amiodarone 300mg |

|

Beta blocker administration |

|

|

Recommendation AGAINST calcium channel blockers |

|

|

Acidosis |

due to risk of worsening hyperkalaemia and hypotension |

|

Hyperventilation |

|

|

Bicarbonates at pH < 7.2 |

|

|

Forced diuresis > 2ml/kg/hr |

Furosemide 0.5mg/kg |

|

|

Mannitol 1g/kg Crystalloids |

Iatrogenic malignant hyperthermia is a life-threatening illness that requires rapid diagnosis and management. Prostaglandins should not be administered on septic patients. The direct correlation between prostaglandins and malignant hyperthermia is fairly established. Distinguishing between idiopathic MH and other hyperthermia-causing factors, such as Serotonin Syndrome (SS), Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) and Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES) is critical.

Patient consent statement: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.

The case was reported at Calais teaching hospital, France.

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

No funding was utilized in the production of this case report.

©2025 Bayoumy. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.