eISSN: 2471-0016

Mini Review Volume 5 Issue 2

1Department of Pathology and clinical pathology, University of Tripoli, Libya

1Department of Pathology and clinical pathology, University of Tripoli, Libya

Correspondence: Al Sayed R Al Attar, Professor of pathology, Department of Pathology and clinical pathology, University of Tripoli, Libya, Tel 2180 9114 99658, Fax 2011 1063 2820

Received: January 01, 1971 | Published: November 9, 2017

Citation: Attar AISRAI, Azreg SAAI, Abdouslam OE. Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) in human and animals: a mini review article and conclusive view. Int Clin Pathol J. 2017;5(2):233–236. DOI: 10.15406/icpjl.2017.05.00129

PVNS is a disease condition affecting the joints in adult males and females and also in animals, it could lead to severe pain, joint deformity and decrease of joint function with a consequent lowering of the productivity. Moreover it is a diagnostic challenge, the difficulty stems from the insidious onset and nonspecific presentation of the disease, as well as its subtle radiographic findings. In addition, the disease is difficult to be differentiated from conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and other inflammatory and neoplastic processes of the synovial lining. PVNS comes in two forms: localized and diffuse. Diffuse PVNS affects the entire synovium and typically occurs in large joints such as the knee or hip. Localized or nodular, PVNS is less common than the diffuse form and typically occurs in smaller joints such as the hands and feet. Involvement of bursa (PVNB, pigmented villonodular bursitis) is the least common. The incidence of pigmented villonodular synovitis is 1.8 cases per 1 million people per year. It is equally affect males and females. Animals are less commonly affected and the condition mostly misdiagnosed. Histopathologically, diffuse disease is characterized by a mononuclear stromal cell infiltrate in the synovial membrane. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages give the characteristic brown color. Additional cell populations include foam cells and multinucleated giant cells. Conclusively, pigmented villonodular synovitis occurre in the synovial membrane of joints and tendon sheaths and characterize by fibrous stroma, hemosiderin deposition, histiocytic infiltrate and giant cells.

Keywords: pigmented, villonodular, idiopathic, synovium, polyarticular, hemosiderin, macrophages, giant cells

PVNS, pigmented villo nodular synovitis; PVNB, pigmented villo nodular bursitis; TMJ, temporo mandibular joint

Joint diseases are one of the most common healthy problems which interfere with the musclo-skeletal functional activates and could lead to severe pain, joint deformity and decrease of joint function with a consequent lowering of the productivity in both human and animals. In this mini review article we will discuss one of the important joint diseases (PVNS), in relation to types, etiology, epidemiology, radiology, pathology and treatment. Pigmented villo-nodular synovitis (PVNS) is a joint disease characterized by inflammation and overgrowth of the joint lining. It usually affects the hip or knee. It can also occur in the shoulder, ankle, elbow, hand or foot. PVNS is idiopathic, it doesn't seem to run in families or be caused by certain jobs or activities.1 PVNS comes in two forms: localized and diffuse. Diffuse PVNS affects the entire synovium and typically occurs in large joints such as the knee or hip. Localized, or nodular, PVNS is less common than the diffuse form and typically occurs in smaller joints such as the hands and feet. Localized PVNS often arises in the form of a large benign tumor on the tendon sheaths of the joint.2 As the tumor grows in the joint, it damages the surrounding bone and tissues.3 Localized PVNS is predominantly found in females and is frequently found in the fingers. PVNS is generally found more in men than women,4 pigmented villonodular synovitis often manifests initially as sudden onset, unexplained joint swelling and pain. Decreased motion and increased pain occur as the disorder progresses. . Moreover it also characterize by hyperplastic synovium, large effusions and bone erosions. Diffuse PVNS symptoms are often confused with those of Rheumatoid arthritis.3 While pigmented villonodular synovitis can occur in both pediatric and geriatric patients, it is more common with ages 20-50.2 Some believe it's caused by abnormal metabolism of fat. Others think it may be caused by repetitive inflammation. The disease was first described as a distinct entity in 1941.5 It remains a diagnostic challenge. The difficulty stems from the insidious onset and nonspecific presentation of the disease, as well as its subtle radiographic findings. In addition, the disease can be difficult to differentiate from conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and other inflammatory and neoplastic processes of the synovial lining.6 The diagnosis of pigmented villonodular synovitis is confirmed by biopsy, and the treatment of choice is synovectomy.2 Uncommon human cases had been reported, Involvement of bursa (PVNB, pigmented villo-nodular bursitis) is the least common. The lesion presented as a painful soft tissue mass in the medial part of the proximal leg.7 Involvement of the temporo-mandibular joint (TMJ) is very rare. Computed tomography clearly reveals areas of lytic bone erosion and sclerosis, Magnetic resonance images invariably show profound hypointensity on both T1 and T2 weighted sequences due to hemosiderin pigmentation.8 Pigmented villonodular synovitis of animals could also be recorded. A 4years old sexually intact male Standard bred trotter was evaluated for left forelimb lameness. Arthroscopic evaluation revealed a large villonodular lesion. The mass was surgically removed. Histpathologic examination of the mass revealed a bed of granulation tissue covered with keratinized epithelium. The authors hypothesize that the lesion developed secondarily to implantation of epithelial cells into a reactive villonodular lesion.9 Four cases of canine villonodular synovitis were diagnosed by histopathology. All four dogs were treated medically with either carprophen or a combination of carprophen and glucosamine complex (Cosequin). In three of the dogs the condition improved significantly, and these dogs returned to normal workload. A 4year old Labrador Retriever was examined because of progressive left hind limb lameness involving the stifle. A villous synovial mass was evacuated by synovectomy. Initially, the macroscopic and histopathological features suggested a malignant fibrosarcomatous process. However, further histological studies revealed lesions consistent with pigmented villonodular synovitis.10A case of severe supra-condylar lysis of the third meta-tarsal bone of a mature Cob gelding had been reported. The gelding presented with moderate to severe lameness and soft tissue swelling in the distal meta-tarsal region. A mass was presented plantar to the third meta-tarsal bone and dorsal to the suspensory ligament branches. It was removed surgically, and found to be a large blood coagulum within an enlargement of the plantar pouch of the meta-tarso-phalangeal joint. The mass was pedunculated and attached to a region of abnormal synovium. This synovium was identified histologically as being an area of villo-nodular synovitis. The lesion had similarities with that of the human. Removal of the abnormal tissue resulted in resolution of the lameness and of the lyses in the third meta-tarsal bone. In equine medicine haemarthrosis should be considered in the list of differential diagnoses for focally mineralised soft tissue masses found within an articulation, and may be associated with pigmented villonodular synovitis.11

Etiology

The etiology of pigmented villonodular synovitis has long been a subject of controversy. Previously this condition was designated “xanthoma” because of the peculiar reaction of the synovial membrane, later many other terms were used, viz, villous arthritis, hemorrhagic villous synovitis, benign and malignant giant cell tumor, xanthogranuloma, myleoplaxoma and pigmented villonodular synovitis.5 Introduced the term PVNS in 1941 to describe a yellow tumor-like synovial lesion.12 The most widely held theory is that the disease is an inflammatory reaction of the synovium.1 However, some evidence exists that it is a benign neoplastic process.13 The exact etiology of (PVNS) is not know.12

Epidemiology

The incidence of pigmented villonodulars ynovitis is 1.8cases per 1million people per year, with no environmental, genetic, ethnic or occupational predilection.14 Most studies show equal prevalence in males and females, although some investigations report a slightly greater predilection in males.14 Pigmented villonodular synovitis generally occurs in patients between the ages of 20 and 45years, but it has been found in patients as young as 11years and as old as 70years.15 The vast majority of patients with pigmented villonodular synovitis have monoarticular complaints of pain and swelling. Only a few reports of poly-articular involvement have been published. In both the localized and diffuse subtypes, the knee is the most commonly affected joint (about 80 percent of patients),16 followed by the hip, ankle, small joints of the hands and feet, shoulder and elbow. The presentations of the disease in the knee and hip are somewhat different.16

Radiology

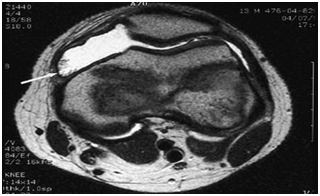

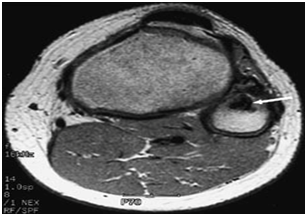

The classic plain radiographic findings of PVNS consist of cystic erosions, increased density of the synovium, secondary to hemosiderin deposition and peri-articular soft-tissue swelling with no calcification.8 Magnetic resonance imaging usually demonstrates key diagnostic features, which include joint effusion, elevation of the joint capsule, hyperplastic synovium and low signal intensity resulting from hemosiderin deposition.2 In patients with diffuse pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may show a large effusion, low signal intensity on both T1 and T2 weighted images (because of hemosiderin deposition), hyperplastic synovium and occasional bony erosions (Figure 1) and (Figure 2).

Figure 1 T2-weighted magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the knee in a patient with pigmented villonodular synovitis. The scan shows a large effusion and villous proliferation arising from the synovial lining (arrow).

Figure 2 T2-weighted MRI scan showing a lesion in the proximal fibula (arrow) that has a low intensity consistent with pigmented villonodular synovitis.

Pathology

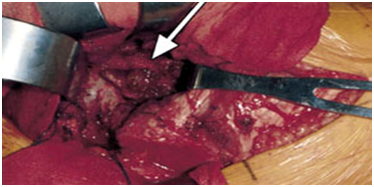

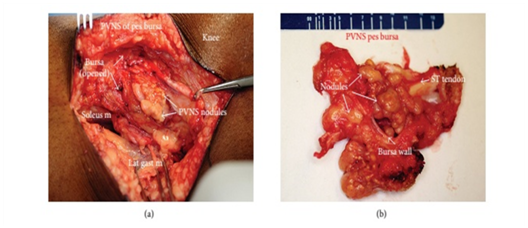

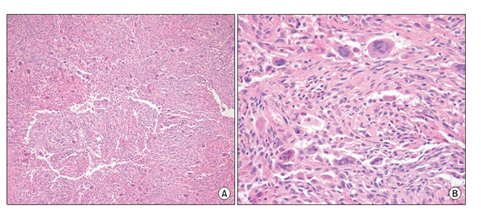

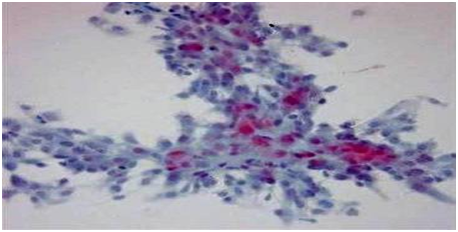

Grossly, pigmented villonodular synovitis appears as a proliferative synovial process with brownish villo-nodular fronds in the affected joints (Figure 3).2 Multiple yellow to brown nodules could be detected in localized types and in the pes anserine bursa (Figure 4). Histopathologically, the tumor is generally represented by many mononuclear histiocytic cells and irregularly interspersed multinucleated giant cells. Hemosiderin pigments could also be detected. Some foamy histiocytic cells may individually interspersed or form clusters (Figure 5).8 Osseous, cartilaginous, and soft tissue involvement was also seen .Fine needle aspiration cytology reveal a few clustered and scattered plump spindle cells containing hemosiderin-pigments and several scattered multinucleated giant cells (Figure 6).

Figure 3 Photograph showing characteristic hypertrophic synoviumv (arrow) and villo-nodular fronds in pigmented villonodular synovitis.

Figure 4 Intraoperative photograph of the lesion (a) and Gross specimen showing multiple yellow to brown nodules inside the pes anserine bursa (ST: semitendinous tendon) (b).

Figure 5 Villo-nodular mass showing many mononuclear histiocytic cells and irregularly interspersed multinucleated giant cells. Hemosiderin deposits are found (H&E staining A×100, B×400).

Figure 6 Smear showing a few clustered and scattered plump spindle cells containing hemosiderin pigments (Papanicolaou staining ×400).

Treatment

The diagnosis of pigmented villo-nodular synovitis is confirmed by biopsy of the synovium. The treatment of choice is synovectomy. Associated bony lesions should be carefully curettaged, and bone grafting should be performed as necessary. Diffuse pigmented villo-nodular synovitis has a high rate of local recurrence (up to 45percent in one review).17 The role of radiation therapy in the management of refractory disease is not clear. In one retrospective series,18 13 of 14patients with recurrent or extensive diffuse disease treated with radiation therapy were disease-free at a mean follow-up period of 69months. Eleven patients showed a good or excellent limb function, and three patients had fair function. Radiotherapy can be considered in patients with previous adequate resection of disease who experience local relapse and in patients with a large amount of disease in whom complete resection is not possible.18 Synovectomy may not relieve all symptoms in patients with significant destructive changes in the joint. In these situations, arthrodesis or total joint replacement should be considered. A series of 11patients with active diffuse pigmented villo-nodular synovitis of the knee treated with synovectomy and total knee arthroplasty showed a local control rate of approximately 70percent and good to excellent joint function at a mean follow-up period of 10.8years.1

Villous, inflammatory nodular diseases of the synovial membrane were first described in the 19th century. pigmented villo-nodular synovitis” was applied to a lesion that occurred in the synovial membrane of joints and tendon sheaths and was characterized by fibrous stroma, hemosiderin deposition, histiocytic infiltrate and giant cells. PVNS is idiopathic, it doesn't seem to run in families or be caused by certain jobs or activities. Diffuse pigmented villonodular synovitis is more predominant and has a high rate of local recurrence. Localized, or nodular, PVNS is less common than the diffuse form and typically occurs in smaller joints such as the hands and feet. It is predominantly found in females and is frequent in the fingers. Pigmented villo-nodular bursitis is the least common. Pigmented villo-nodular synovitis of animals could also be recorded with somewhat structural and behavioral similarities the diagnosis of pigmented villo-nodular synovitis is confirmed by biopsy of the synovium. The treatment of choice is synovectomy. Associated bony lesions should be carefully curettaged, and bone grafting should be performed as necessary.

The authors appreciate the support provided by the authority of the University of Tripoli, Libya and the professional technical help of miss Torkia Aduma.

The author declares there are no conflicts of interest.

©2017 Attar, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.