eISSN: 2373-6372

Case Report Volume 13 Issue 5

Department of Surgery, Hospital Ángeles Lomas, Mexico

Correspondence: Alejandro Weber Sánchez, Department of Surgery, Hospital Ángeles Lomas,Vialidad de la Barranca s/n, Consul 410,Valle de las Palmas, Huixquilucan, Edo. Mexico, Tel +52 5552469527

Received: September 26, 2022 | Published: October 26, 2022

Citation: Rodrigo SH, Rafael CR, Alejandro WS. Obstructing colon cancer presenting as toxic megacolon. Gastroenterol Hepatol Open Access. 2022;13(5):190-192. DOI: 10.15406/ghoa.2022.13.00521

Introduction: Colon cancer is the most frequent cause of colonic obstruction which is usually manifested by distention, bloating, and pain. Colonic obstruction with a competent ileocecal valve is a risk factor for complications such as ischemia, necrosis, perforation, but toxic megacolon is seldom mentioned in literature.

Case report: This case describes a patient with left sided colon cancer presenting initially with obstructive symptoms that developed into a serious toxic megacolon within a few hours. Emergent surgery was performed. Descending and transverse colon were 20cm in diameter so left sided hemicolectomy was performed with end colostomy. In our literature review, several references mention that cancer is a potential cause of toxic megacolon, but with no reported source to state this. A PubMed search did not offer any results for toxic megacolon associated to cancer when C. difficile or colitis were excluded.

Conclusion: Colon cancer is not usually associated with toxic megacolon. Making a late decision to perform urgent surgery increase the rate of complications and worse prognosis.

Keywords: toxic megacolon, colon cancer, laparoscopy, chemotherapy

Toxic megacolon is a rare, but potentially life-threatening complication, associated with systemic toxicity and acute transmural inflammation and possible necrosis of the colon. Colon cancer is not traditionally associated with toxic megacolon because of its early definition; however, obstruction is a potential cause that can have other potential triggers. The goal of this case report is to present an atypical clinical presentation for colon cancer.

A 76-year-old male with no family or personal relevant medical history, presented to the emergency department complaining of 15days of nausea; 3days before he was seen, he suffered of progressive bloating, constipation, colicky diffuse abdominal pain, and abdominal distension. During his evaluation, he had normal vital signs, diffuse abdominal pain and distension without any other relevant findings. Blood work found a white blood cell (WBC) count of 7,800/uL. Computed tomography (CT) scan with oral and intravenous contrast was performed finding a 4.7 by 3.8cm tumor in the rectosigmoid junction with radiological signs suggestive of necrosis, obliterating 90% of the lumen; proximal colonic distention of up to 8.7cm in the hepatic flexure, coprostasis, and diffuse thickening of the wall of the descending colon (Figure 1). A nodule of 1.6 cm in segment VII of the liver was also found.

Figure 1 Computed tomography showing tumor obliterating 90% of the lumen (yellow arrow) and colonic dilation (yellow arrowhead). Taken 12/17/21 with permission of the patient, in the archives of Alejandro Weber M.D. chief surgeon.

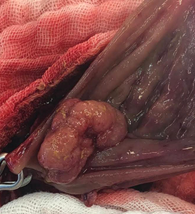

While on colonic preparation for colonoscopy 12hours later, he presented worsening of pain, abdominal distension, fever, hemodynamic instability and WBC count increased to 14,300/uL. Emergent surgery had to be performed, finding descending and transverse colon with loss of haustration and 20cm in diameter (Figure 2). Open left sided hemicolectomy was performed with end colostomy. During ostomy formation, an additional synchronous sessile tumor of approximately 5cm was found and resected in the colostomy’s mucosa. (Figure 3) No hepatic resection of the hepatic mass was done due to the urgent setting.

Figure 2 Eviscerated colon immediately after laparotomy. Taken 12/18/21 with permission of the patient, in the archives of Alejandro Weber M.D. chief surgeon.

Figure 3 Sessile polyp incidentally found during colostomy formation. Taken 12/18/21 with permission of the patient in the archives of Alejandro Weber MD.

Nasogastric (NG) tube was inserted during surgery, obtaining 2L of fecaloid fluid. Patient was sent to the intensive care unit (ICU) requiring vasopressors, mechanical ventilation and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Partial parenteral nutrition (PN) was started in the first 24hours after surgery. Because of respiratory distress due to pulmonary edema, he remained in ICU for ten days. Diarrheal stools tested positive for Clostridioides difficile, and oral Vancomycin was administered for the next 10days. Due to intolerance, complete oral intake could only be started 15days after the surgery, NG tube was withdrawn and PN suspended at day seventeen.

Pathology reported a moderately differentiatied adenocarcinoma of 4 by 3cm, with perineural invasion. Second neoplasm was a villius adenoma with no evidence of malignancy.

Patient was discharged from the hospital at day 22. Control PET/CT was negative and no longer showed the hepatic lesion on segment VII (Figure 4). Colonoscopy was performed 6 months after the first surgery without significant findings, and he underwent re-connection of the colon transit through a laparoscopic approach. The metastatic nodule over the liver was searched for even with the laparoscopic ultrasound and indocianyne green, but it was no longer found. The patient had an uneventful recovery from the surgery, tolerated oral diet on day three, and was discharged from hospital on day five. Patient is still in close follow-up receiving adjuvant chemotherapy to this day without any evidence of recurrence, and doing his daily routines uneventfully.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cause of cancer in the United States, approximately 70% of which appears in the colon.1 Symptoms for colonic cancer (CC) are diverse and unspecific. The most common symptoms are changes in the bowel habits. About 74% of patients report changes prior to their diagnosis.2 Due to the narrowing of the distal colon, changes of the stools and changes in bowel habits are more frequent in left sided cancer. The same is true for colonic obstruction and pain.

Colorectal carcinoma is diagnosed by histologic examination of biopsies obtained through colonoscopy or surgical specimen, as in this patient, due to the emergency surgery. Most CRC are adenocarcinoma. Synchronous lesions are found in 3 to 5% of patients during colonoscopy.3 The second tumor found while constructing the colostomy was villius adenoma with no evidence of malignancy but potential of malignancy. Even experienced operators could miss CRC detection in 2 to 6%. 4

Other methods of diagnosis include flexible sigmoidoscopy, PILLCAM and CT colonography, with varying degrees of sensitivity and specificity.

T1 and T2 lesions with no evidence of regional or distant metastasis do not require staging.5 Staging for CRC for tumors at stage II or more require at least a thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic CT scan, which has a sensitivity of 75 to 87% for detecting distant metastasis.6 When in doubt, liver MRI can be performed to better delineate hepatic lesions when CT findings are not definitive.7 The hepatic nodule found was not resected because we had not identified it as liver metastasis, as was after the PET/CT, but after quemotherapy, no evidence of metastasis was found and during the reconnection surgery, neither was found, even with the use of laparoscopic ultrasound and indocyanine green.

Toxic megacolon was traditionally defined as colonic dilation in the context of systemic toxicity due to inflammatory bowel disease or infection.8 More recently, it has been noted that any infectious or inflammatory condition, including obstruction, can cause a toxic dilation of the colon.9

Pathogenesis for toxic megacolon is not well defined, but it is thought that inflammation of the colon induces the release of nitric oxide, inhibiting muscle tone and contributing to dilation.10

Toxic megacolon is suspected in patients with colonic dilation of 6 cm or more and evidence of systemic toxicity.11 Tomographic findings of toxic megacolon are listed in Table 1 12, histologic hallmarks in Table 2. 13 In the case of this patient, colonic preparation and radiopaque contrast media could have contributed to the acute toxic presentation.

|

Table 1 Tomographic findings of toxic megacolon

|

Table 2 Histologic hallmarks of toxic megacolon

Non operative management of toxic megacolon aims to reduce inflammation, restore motility and reduce perforation rates. This management can prevent up to 50 percent of surgeries.14 Need for surgery and the best moment to do it is currently a matter of debate. Making a late decision is known to increase the rate of complications, worsening the prognosis.15 In this case, urgent surgery was needed because acute deterioration. Care in the ICU with broad spectrum antibiotics is normally required because of the systemic toxicity and strong inflammatory response. Bowel rest and nasogastric tube decompression need to be considered if necessary as well as parenteral nutrition as in this case. 16

1 Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7–33.

2 Thompson MR, O'Leary DP, Flashman K, et al. Clinical assessment to determine the risk of bowel cancer using Symptoms, Age, Mass and Iron deficiency anaemia (SAMI). Br J Surg. 2017;104:1393.

3 Mulder SA, Kranse R, Damhuis RA, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of synchronous colorectal cancer: a Dutch population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;35(5):442.

4 Bressler B, Paszat LF, Chen Z, et al. Rates of new or missed colorectal cancers after colonoscopy and their risk factors: a population-based analysis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(1):96–102.

5 NCCN guidelines: National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). USA: NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology; 2022.

6 Nerad E, Lahaye MJ, Maas M, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of CT for Local Staging of Colon Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207(5):984.

7 Sahani DV, Bajwa MA, Andrabi Y, et al. Current status of imaging and emerging techniques to evaluate liver metastases from colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2014;259(5):861–872.

8 Sheth SG, LaMont JT. Toxic megacolon. Lance. 1998;351:509.

9 Ausch C, Madoff RD, Gnant M, et al. Aetiology and surgical management of toxic megacolon. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8(3):195–201.

10 Mourelle M, Casellas F, Guarner F, et al. Induction of nitric oxide synthase in colonic smooth muscle from patients with toxic megacolon. Gastroenterology. 1995;109(5):1497.

11 Autenrieth DM, Baumgart DC. Toxic megacolon. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(3):584.

12 Moulin V, Dellon P, Laurent O, et al. Toxic megacolon in patients with severe acute colitis: computed tomographic features. Clin Imaging. 2011;35(6):431–436.

13 Norland CC, Kirsner JB. Toxic dilatation of colon (toxic megacolon): etiology, treatment and prognosis in 42 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1969;48(3):229–250.

14 Fazio VW. Toxic megacolon in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's colitis. Clin Gastroenterol. 1980;9(2):389–407.

15 Mai CM, Yeh CC. Toxic megacolon with abdominal compartment syndrome. J Trauma. 2011;71(2):E44.

16 Dickinson RJ, Ashton MG, Axon AT, et al. Controlled trial of intravenous hyperalimentation and total bowel rest as an adjunct to the routine therapy of acute colitis. Gastroenterology. 1980;79(6):1199–204.

Colon cancer is not usually associated with toxic megacolon. As a cause for obstruction, it should be considered when a patient presents with toxic megacolon signs or symptoms, prompting a rapid change from non-operative management to emergent surgery. Surgical management depends on patient’s stability, tumor resectability or the need for a diverting palliative procedure.

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report. The figures were obtained by the chief surgeon, with the written consent permission of the patient to be published.

None.

Author declares there are no conflicts of interest towards the article.

None.

©2022 Rodrigo, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.