eISSN: 2373-6372

Research Article Volume 11 Issue 3

1Unidade de Cirurgia Pediátrica, Hospital Prof. Doutor Fernando Fonseca, Portugal

2Serviço de Cirurgia Pediátrica, Hospital Dona Estefânia- CHULC, Portugal

Correspondence: Sofia Ferreira de Lima, Hospital Dona Estefânia- CHULC, Rua São João da Mata 150 1200-852 Lisboa, Portugal, Tel +351 913104672

Received: April 28, 2020 | Published: June 5, 2020

Citation: Lima SF, Knoblich M, Borges C, et al. Clinical manifestations of Meckel Diverticulum in children: a review of 11-years. Gastroenterol Hepatol Open Access. 2020;11(3):118-121 DOI: 10.15406/ghoa.2020.11.00425

Introduction: The preoperative diagnosis of Meckel’s diverticulum is often difficult to establish because clinical symptomatology is non-specific and diagnostic methods have low sensibility and specificity. This study aimed to review the experience in a tertiary pediatric hospital while evaluating the management strategies.

Methods: We retrospectively analysed the clinical data of all patients (≤17years of age) with Meckel’s diverticulum who underwent surgery at our centre between 2008 and 2019. Patients who underwent incidental diverticulectomy or whose histopathological reports did not confirm Meckel’s diverticulum were excluded from analyses. Clinical, imaging, laboratory, surgical and pathological data were recorded.

Results: The patients included 29 boys and 3 girls aged from 2months to 17years. Fourteen patients were diagnosed with intestinal obstruction, 12 cases presented with lower gastrointestinal bleeding and 6 cases demonstrated symptoms of diverticulitis. The preoperative diagnostic rate of Meckel’s diverticulum was 43,8%. Among the 12 cases of intestinal bleeding, 10 patients underwent a Tc- 99m scan that showed a positive tracer in 6 patients; there were 4 false negative results. The percentages of laparotomic and laparoscopic procedures were 78,1% and 21,9%, respectively. The preferable surgical technique was segmental bowel resection (93,8%). Postoperative histopathology revealed ectopic gastric or pancreatic tissue in 24 patients. There was a wound dehiscence and a sub-occlusion that were resolved with conservative treatment.

Discussion: Integrative application of multiple approaches such as traditional imaging methods, Tc-99m Meckel’s scan, capsule endoscopy, and laparoscopy can help us to achieve a more accurate diagnosis, while decreasing misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis.

Keywords: children, gastrointestinal bleeding, meckel diverticulum, laparoscopic-assisted diverticulectomy, scintigraphy with Tc-99m pertechnetate

MD, Meckel’s diverticulum; CT, computed tomography; SD, standard deviations; SPECT, Single-photon emission computed tomography; MRI, Magnetic resonance image; WCE, Wireless capsule endoscopy

Meckel’s diverticulum (MD) is the most common congenital gastrointestinal malformation in children.1–3 This develops as a result of incomplete obliteration of vitelline duct around the 5th to 7th weeks of gestation. Its incidence is estimated to be between 0,3% and 2,9% of the general population, however in most patients it’s clinically silent and often an incidentally finding during surgery.1,4 The risk of developing clinical manifestations is estimated to be about 4,2% of the MD patients, but this risk reduces with age5,4. This condition can cause many complications, such as gastrointestinal hemorrhage, intestinal obstruction (including intussusceptions, volvulus, torsion of MD, internal hernia, Littre hernia), diverticulitis with or without perforation or rarely malignant degeneration.2,6

The preoperative diagnosis of MD is often difficult to establish not only because is rarely observed in children but also because the clinical symptomatology is non-specific and polymorph; besides this the traditional diagnostic methods such as abdominal radiography, ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT) or scintigraphy with Tc-99m pertechnetate often produce false-negative or false-positive results.1,2,7 MD can cause serious consequences such as shock, intestinal perforation and sepsis; Clinicians need to be aware of these to promptly suspect and intervene and to pursue better outcomes.1,8 In order to provide more information to pediatricians and pediatric surgeons for early diagnosis and treatment, this study aimed to review the experience in a tertiary pediatric hospital while evaluating the management strategies.

A retrospective study of pediatric patients (≤ 17years of age) with MD who underwent surgery at Dona Estefânia Hospital (Lisbon, Portugal) between January 2008 and March 2019 was conducted. Patients were identified by chart review according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD.9-CM) and Tenth Revision (ICD.10) codes 751.0 and Q43.0 respectively for Meckel’s diverticulum. Patients who underwent incidental diverticulectomy or whose histopathological reports did not confirm MD were excluded from analyses. The demographic characteristics, clinical manifestations, imaging studies, surgical procedure performed, intraoperative and histological findings and follow-up were reviewed and analysed. The data was analysed using descriptive statistical procedures for calculating means, standard deviations (SD) and percentages. These analyses were conducted with Microsoft ®Excel® for Office 365, version 1902.

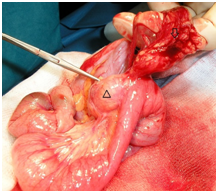

During a 11-year period, thirty-two children (29 boys, 3 girls) were enrolled in the current study. The patients’ ages ranged from 2months to 17years (median 5years) with 6 cases with less than 2years old, 9 cases with ages between 2 and 5years old, 9 cases with ages between 5 and 9years old, and 8 cases aged 10 or more years old. The diverticular pathology was denoted by inflammatory, occlusive or bleeding phenomena. Thus of 32 cases, 14 were diagnosed as intestinal obstruction (43,8%), 12 cases presented with lower gastrointestinal bleeding (37,5%) and 6 cases showed symptoms of diverticulitis (18,8%). Among the causes of intestinal occlusion, there were 9 cases of intussusception, 3 cases of mesodiverticular band causing occlusion (by direct compression, induction of volvulus or internal hernia), one case of MD torsion and one case of adhesions from MD to cecum. With respect to major symptom, among the total of patients, abdominal pain was found in 20 cases (62,5%), while vomiting was found in 18 cases (56,2%), lower gastrointestinal bleeding was found in 12 cases (37,5%) and fever in 7 cases (21,9%) (Figures 1–4).

Figure 3 Operative photograph of Meckel diverticulum (∆) adhesions(↓) that caused intestinal occlusion.

Figure 5 Operative photograph of Meckel Diverticulum exteriorized trough the umbilicus incision and the two ports positions in a transumbilical video-assisted Meckel Diverticulum resection.

Multiple imaging studies were performed to assist the diagnosis, depending on the clinical presentations of patients, including abdominal radiography, abdominal ultrasonography, abdominal Computed Tomography, Meckel’s scan, upper digestive endoscopy, capsule endoscopy, colonoscopy, upper gastrointestinal contrast study and contrast enema. The presurgical diagnosis of MD was suspected in 14 cases (43,8%), mostly in the group of intestinal bleeding complication (75% of intestinal bleeding cases, 33% of intussusceptions and 17% of diverticulitis cases had a preoperative diagnosis). In this study the diagnostic methods with better acuity were Meckel scan (63,6%, n=11), followed by capsule endoscopy (33%, N= 3), abdominal CT (25%, N=4) and abdominal ultrasonogram (21,4%, N= 28).

Amongst 12 cases of intestinal bleeding, 10 patients underwent a technetium Tc-99m pertechnetate Meckel’s scan before surgery and 6 showed positive results. There were four false negative results: one of these underwent repeated Meckel scanning, which detected ectopic gastric mucosa; another patient underwent a capsule endoscopy that revealed MD; the other two underwent laparoscopy, which demonstrated MD. According to the results of blood test performed to the patients with intestinal bleeding the haemoglobin mean was 7,7g/dl (±2, range 3,9 to 10,6g/dl). All cases of intestinal bleeding had heterotopic mucosa on histological analysis except one, which wasn’t submitted to scintigraphy and the mucosa type was not referred on the report.

Surgical approaches were selected according to the clinical presentations. Overall, the percentages of laparotomic and laparoscopic procedures were 78,1% and 21,9%, respectively. Laparoscopic procedures consisted in diagnostic laparoscopy and performing segmental bowel resection or diverticulectomy extracorporeally, thorough the umbilical port. The patients who underwent laparoscopic-assisted procedures (n=7) had gastrointestinal bleeding MD complication (71,4%), the remaining had a Meckel diverticulitis and an intussusception. The preferable surgical technique was segmental bowel resection (93,8%). The remaining 2 patients were managed by simple diverticulectomy (both patients had gastrointestinal bleeding). Postoperative histopathology revealed ectopic gastric mucosa in 23 patients (72%), ectopic pancreatic tissue in one patient and both gastric and pancreatic ectopic tissue in 2 patients (6,3%). There were 3 cases of absent heterotopic mucosa, 3 cases where it wasn’t possible to analyse mucosa due to necrosis, and 2 cases where the type of mucosa was not referred (one case of MD hemorrhage and one case of Meckel diverticulitis). Follow-up was from 0 days to 22months (mean 3 months, standard deviation 4,8 months). All patients recovered uneventfully except 2 (6,3%) in whom there were a wound dehiscence and a readmission for presumed adhesive sub-occlusion one month after surgery, which were resolved with conservative treatment.

The incidence of Meckel diverticulum in the general population has been estimated at approximately 2% but reports from autopsy and retrospective studies range from 0,14% to 4,5%.8 Usually, MD is symptomatic within the first 2 years of life (almost 50%), according to the known rule of two. In our series, the median of age at the time of diagnosis was 5years, which is similar to the results of other studies;5–9 only 18,8% of patients were younger than 2 years old, and there were the same proportion of patients between 2 and 5years and between 5 and 9years (28,1%). The male-to-female ratio in this study was nearly 10:1, which reflects the great disparity in incidence between genders in this gastrointestinal malformation. Other studies showed male-to-female ratios of 7,5:1, 15:4, which is substantially higher than the stated 2:1 of the rule of 2.7,10

Preoperative diagnosis of symptomatic Meckel’s diverticulum is a challenge, particularly for the patients presenting with symptoms other than bleeding. Quite varied clinical presentations and decreased sensitivity and specificity of traditional diagnostic methods, such as X-ray and ultrasound, CT and Magnetic resonance image (MRI), are the main causes of low preoperative detection rate.1,4,7 These conventional diagnostic methods remain indispensable in differential diagnosis of MD and assessing the indication for surgical intervention; ultrasonography remains the first choice of examination in diagnosing MD associated with intussusception or diverticulitis.1

Tc-99m scan is an accurate non-invasive method of preoperative investigation for Meckel diverticulum containing ectopic gastric mucosa with overall sensitivity of 80 to 90%, specificity of 95% and accuracy of 90% in children.2,8 As MD is the most common cause of small intestinal bleeding in children, Tc99m is specially indicated in cases of painless intestinal bleeding although has a false negative rate of 33,3%, like the result of our series (36%).11 False-negative diagnosis may be due to ulcers and hemorrhage without ectopic gastric mucosa to capture Tc-99m or if the area of ectopic gastric mucosa is very small and can be missed on the Meckel’s scan;7 alternatively, if there is profuse bleeding or an accentuated intestinal transit, the radioisotope can be washed out.3,7 Several techniques have been introduced to increase the sensitivity. Premedication with histamine H2 blockers, glucagon, and pentagastrin, bladder lavage, nasogastric suctioning and recently Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and SPECT/CT have been reported to increase sensitivity.2 A repeat scan is another method to increase sensitivity and accuracy, thus being sometimes requested in patients with persistent gastrointestinal bleeding, high suspicion for Meckel diverticulum and negative or equivocal first Meckel scan.2,4,6 This has been done in our series in one of the cases of false negative Tc-99m scan, which was advantageous. Restricting use of the test to certain indications such as anemic patients with intestinal hemorrhage is also important to ensure high sensitivity and specificity4. For children with obstructive symptoms the utilization of radiological or sonographic modalities is preferred to a Meckel’s scan because MD accounts for only a small fraction of intestinal obstruction.6

Wireless capsule endoscopy (WCE) is a novel, noninvasive diagnostic technique that may aid in the diagnosis of a bleeding MD. In our series WCE was used after a false-negative scintigraphy and it confirmed the MD preoperative suspicion. But the shortcomings of capsule endoscopy are also evident, such as the limitation of patient’s age range, potential risks of delayed passage and obstruction requiring surgical removal which restricts the widespread application in the pediatric population.1

As we can see in our series most of diagnoses were made in the surgery (56,2% of cases) despite the multiple diagnostic methods used previously. In recent years, laparoscopic surgery has been recognized as a safe and minimally invasive surgical technique associated with short hospital stays and minimal complication rates.8 Currently, laparoscopy is a well-established initial step for establishing the diagnosis and subsequent management of MD in children.1,7 It should be the first option in cases of intestinal bleeding in which MD is a strong suspicion, even though the diagnostic exams don’t confirm.

In our series most of patients were treated in the laparotomy conventional way, although 85% of cases treated with laparoscopy occurred in the last 5years, which reflects a trend towards minimal invasive surgery. The patients who underwent laparoscopic-assisted procedures were mostly from the gastrointestinal bleeding complication group. We believe that most surgeons would approach children with obstruction in open fashion. Alternatively, in children with bleeding, a higher level of suspicion for MD may be present and as such surgeons are likely more confident that the problem can be approached laparoscopically.12 In our series a trans-umbilical video-assisted surgery was the chosen approach, in which the small bowel is exteriorized through extension of the umbilical port site. We believe that the trans-umbilical video-assisted surgery is easier and faster with similar cosmetic results when compared to intracorporeally laparoscopy, thus possibly helping to bridge the experience gap between the open and laparoscopic approaches and may facilitate avoidance of open laparotomy.

The surgical approach to MD may vary depending on its morphology and anatomical variations, such as a short diverticulum with a wide base or long diverticulum with a narrow base.4 Surgical management options are simple diverticulectomy or wedge excision of the adjacent ileum or segmental ileal resection and anastomosis; this seems to be the most popular surgical procedure for MD as we can also observe in our series, in which all cases except two were treated by intestinal resection/anastomosis. Diverticulectomy has been considered a procedure that carries the risk of leaving heterotopic mucosal tissue or ileal ulceration in the adjacent bowel. Alternatively advocates of diverticulectomy-only contend that the ulcerated intestinal mucosa is immediately adjacent to the heterotopic gastric mucosa, which itself originates in the diverticulum and that removal of this acid-producing source is enough to prevent further bleeding.4,9,11 In fact, some recent studies showed that in children presenting with a bleeding MD, diverticulectomy-only is safe and completely resects gastric heterotopia. Furthermore, operative times and hospitalization are shortened significantly without increasing risk of continued bleeding, with lower overall complication rate and eliminates the contaminated surgical field.9,11

Postoperative morbidity is reported to be 5,3%, with wound infections and adhesive intestinal obstruction being some of the most common complications, which we also observed in our series; both resolved with conservative treatment.4,7 This study is associated with some limitations. It is a relatively small retrospective review and has a short follow-up. The positive aspect is that it gives information about the incidence, diagnosis and treatment of this common gastrointestinal malformation in a tertiary pediatric hospital in the Portuguese capital.

In conclusion, MD is an important differential diagnosis in paediatric patients presenting with abdominal pain and fever, intestinal occlusion or gastrointestinal bleeding and it remains a challenge in preoperative diagnosis. Delayed diagnosis may cause extremely serious complications, possibly resulting in life-threatening consequences, so physicians need to bare MD in mind. Integrative application of multiple approaches such as traditional imaging methods, Meckel’s scan, capsule endoscopy, and laparoscopy can help us achieve a more accurate diagnosis, while decreasing misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis.

None.

The authors declare that there were no conflicts of interest in conducting this work.

There were no external funding sources for the realization of this paper.

©2020 Lima, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.