eISSN: 2373-6372

Case Report Volume 11 Issue 4

1Department of Internal Medicine, Woodhull Medical and Mental Health Center, USA

2Department of Internal Medicine, Metropolitan Hospital, USA

Correspondence: Bergasa Nora, Department of Internal Medicine, Woodhull Medical and Mental Health Center, USA, Tel 212-423-6771

Received: July 11, 2020 | Published: August 4, 2020

Citation: Roshan P, Ahmed S, Tarek AH, et al. Characterization of patients with chronic hepatitis C attended at a hepatology clinic of a community hospital in North Brooklyn in New York city. Gastroenterol Hepatol Open Access. 2020;11(4):141-146. DOI: 10.15406/ghoa.2020.11.00430

Background: Screening for chronic hepatitis C (C-HCV) is an important public health measure to prevent its complications. Thus, the aim of this study was to characterize the population of patients with C-HCV attended at a hepatology clinic in North Brooklyn in New York City.

Methods: Relevant clinical data were collected retrospectively by chart review of patients with C-HCV, at least 18 years old, attended between 2005 and 2019, period chosen because of feasibility.

Results: 258 patients were identified of whom 156(60%) were men, with a mean age of 59.3years (yrs) (29-87), 46(18%) being up to 50, and 172 (67%) in the baby boomer category. Risk factors were intravenous drug use (IDU) in 87(34%), blood transfusions in 29 (11%), tattoos in sixteen (6%), twelve (5%) multifactorial, and unknown in 98 (38%) patients. The majority had an abnormal serum liver profile. The most common genotype was 1a. 205 (79%) were treatment naïve (TN) and 51(20%) experienced (TE). Of the TE, 38(75%) had been treated with interferon/ribavirin, and the rest with direct acting agents (DAA). All patients treated de novo received DAAs approved in or after 2014. Sustained virological response (SVR), i.e. cure, and was documented in 176 patients (71%) at weeks 12 or 24 post-treatment. Lack of adherence to follow up was an important barrier to cure.

Conclusions: Treatment of C-HCV was effective in the diverse community of North Central Brooklyn, however, programs to improve adherence to treatment are necessary. Additionally, the expansion of screening for C-HCV beyond baby boomers is paramount in its eradication.

SVR, sustained virological response; DAA, direct acting agents; TN, treatment naïve; HCV, hepatitis C virus; C-HCV, chronic hepatitis C

Chronic hepatitis C (C-HCV) is a disease of global importance with significant societal and economic burdens. Based on 2011 data, there was a total economic burden of 6.1billion US dollars per annum attributed to HCV-related liver disease.1

In 2017 the rate of newly reported cases of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in New York City was more than double the rate of new cases of HIV.2 Despite the overall declining rate of newly reported HCV infections in New York City, there were still 5,308 cases reported in 2017.3 The borough of Brooklyn accounted for the majority of these cases at 29.4%.3 Accordingly, the aim of this study was to characterize the patients with C-HCV attended at a Hepatology clinic of a community hospital in north Brooklyn to identify areas to improve patient care.

This study was a retrospective chart review of patients who had been seen at the hepatology clinic at least once between 2005 to 2019, were at least 18years old, and had a diagnosis of C-HCV as defined by the CDC.4 Demographic and clinical data were collected. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

258 patients were identified. 156(60%) of the patients were males with an average age of 59.3years (range 29-87) (Table 1). 172(67%) were baby boomers, defined as an age range of 54 to 73years old. 119 patients (46%) were diagnosed with C-HCV after 2013, coinciding with the screening recommendation made by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) in 2013.5 In cases where it was documented, 87 patients (33%) acquired the infection by intravenous drug use (IDU), 29(11%) by blood transfusion, sixteen (6%) by tattoos, and fifteen (6%) by risky sexual behaviour. Twelve patients (5%) had multiple risk factors identified. 72 patients (27%) had comorbid alcohol misuse. Figure 1 displays the country of origin of the study population. Of those where the country of origin was known, 83 (32%) had been born in the USA, 58 (22%) in Latin America, nine (3%) in Africa, eight (3%) in Europe, two (<1%) in Russia, and one (<1%) in the Caribbean. Of those with documented race or ethnicity, 95 (37%) were Hispanic, 72 (28%) were black, and fifteen (6%) were white (Figure 2).

|

Category |

Number of individuals |

|

Age |

|

|

Baby boomers |

172(66.7%) |

|

50 years old and younger |

46(17.8%) |

|

Gender |

|

|

Male |

156(60.5%) |

|

Female |

102(39.5%) |

|

Date of diagnosis |

|

|

Unknown |

31(12.0%) |

|

Prior to 2013 |

108(41.9%) |

|

After 2013 |

119(46.1%) |

|

Route of infection |

|

|

Intravenous drug use |

87(33.7%) |

|

Blood transfusion |

29(11.2%) |

|

Tattoo |

16(6.2%) |

|

Risky sexual behavior |

15(5.8%) |

|

Dental procedure |

1(0.4%) |

|

Multiple risk factors |

12(4.7%) |

|

Unknown |

98(38.0%) |

|

Alcohol abuse |

|

|

Yes |

72(27.9%) |

|

No |

183(70.9%) |

|

Unknown |

3(1.2%) |

Table 1 Age, gender, date of diagnosis, route of infection, and co-morbid alcohol abuse of the Study population

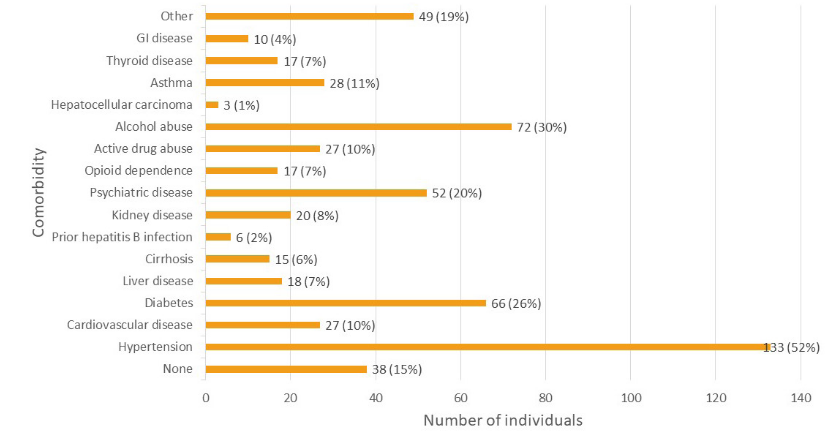

The most common comorbidities were hypertension (133 patients) and diabetes (66 patients) (Figure 3). 52 (20%) patients had comorbid psychiatric conditions. 27(10%) patients were active substance abusers. Six (2%) patients were noted to have had a previous resolved hepatitis B infection. Fifteen (6%) patients were identified as having cirrhosis. Further comorbid disease is specified in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Number of individuals with various comorbid diseases in the study population. Cardiovascular disease excludes hypertension. Liver disease includes cirrhosis but excludes hepatitis B. GI disease excludes all forms of liver disease. Psychiatric disease included major depression, PTSD, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia subtypes.

Table 2 outlines laboratory data. The majority of patients, 162(63%), had serum alanine transaminase (ALT) activity levels greater than one and less than five times the upper limit of normal (ULN), followed by 77 patients (30%) with normal levels. Eighteen patients (7%) had levels greater than five times the ULN and only 1 patient had a level greater than ten times the ULN. In contrast, the majority of patients had normal serum activity of alkaline phosphatase (ALP),177 patients (67%), with 79 patients having activity greater than one and less than five times the ULN, and only two patients having levels greater than five the ULN. The most common genotype was 1a, documented in 150 patients (57%), followed by 1b in 58 patients (22%) (Figure 4). The genotypes of the remaining 42 individuals are outlined in Figure 4.

|

Laboratory data |

Number of individuals |

|

Level of serum ALT activity |

|

|

Normal |

77(29.8%) |

|

>1 to <5 times ULN |

162(62.8%) |

|

>5 times ULN |

18(7.0%) |

|

>10 times ULN |

1(0.4%) |

|

Level of serum ALP activity |

|

|

Normal |

177(68.6%) |

|

>1 to <5 times ULN |

79(30.6%) |

|

>5 times ULN |

2(0.8%) |

|

HCV genotype |

|

|

1a |

150(58.1%) |

|

1b |

58(22.5%) |

|

1 |

4(1.6%) |

|

2a/2c |

2(0.8%) |

|

2b |

6(2.3%) |

|

2 |

8(3.1%) |

|

3a |

6(2.3%) |

|

3 |

12(4.7%) |

|

4a/4c/4d |

6(2.3%) |

|

4 |

5(1.9%) |

|

Unknown |

1(0.4%) |

Table 2 AST and ALP activity levels of the study population

Treatment data are outlined in Table 3. 205 patients (79%) were treatment naive (TN) and 51 (20%) were treatment experienced (TE). Of the TE, the majority (38 patients; 75%) were treated with interferon/ribavirin (R). The details of prior treatment for the remaining patients are provided in table 3. In terms of current treatment, all patients were most recently treated with direct acting agents (DAA) approved in or after 2014 (Figure 5). The most common DAA used was ledispasvir/sofosbuvir, prescribed to 123 patients (48%). Other drugs used were sofosbuvir/velpatasvir in 46 patients (18%), elbasvir/grazoprevir in 33 patients (13%), and glecaprevir/pibrentasvir in 20 patients (8%). Nine patients did not receive any treatment due to lack of adherence to appointments.

|

Historical treatment data |

Number of individuals |

|

History of prior treatment |

|

|

Yes |

51(19.8%) |

|

No |

205(79.5%) |

|

Unknown |

2(0.8%) |

|

Prior treatment medication |

|

|

Interferon/Ribavirin |

38(14.7%) |

|

Boceprevir |

2(0.8%) |

|

Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir |

1(0.4%) |

|

Sofosbuvir |

1(0.4%) |

|

Interferon/Sofosbuvir/Simeprevir |

1(0.4%) |

|

Elbasvir/Grazoprevir |

1(0.4%) |

|

Elbasvir/Grazoprevir/Ribavirin |

1(0.4%) |

|

Interferon/Ribavirin/Sofosbuvir |

1(0.4%) |

|

Sofosbuvir/Simeprevir |

1(0.4%) |

|

Sofosbuvir/Ribavirin |

1(0.4%) |

|

Interfron/Ribavirin/Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir |

1(0.4%) |

|

Unknown |

2(0.8%) |

Table 3 Historical treatment data of the study population

Treatment outcome is displayed in Figure 6. HCV RNA was documented as negative in 177 patients (69%) at 12 or 24 weeks post-treatment, consistent with sustained virological response (SVR). Thirteen patients (5%) had negative HCV RNA at the end of treatment (EOT) and no further follow up. Two patients had detectable RNA at EOT, while five patients relapsed post-treatment (subsequent detectable HCV RNA after documented non-detectable levels). 51 patients (20%) were started on therapy but did not adhere to follow up. At the time the data were collected, nine patients were still undergoing treatment. One patient expired during treatment due to reasons unrelated to their therapy.

This study was conducted to characterize the patients with chronic hepatitis C attended at a hepatology clinic in a community hospital in north Brooklyn and it revealed that the majority of subjects was comprised of male baby boomers of Hispanic ethnicity; however 65 (25%) were from generation X and Millennials. The most common risk factor was IDU, the most common genotype was 1a, and most patients had substantial inflammatory activity based on serum ALT. Treatment was associated with cure in the majority of patients.

Of those in whom it was known, just over half of the patients were born in the US and greater than one third from Latin American countries. Consistent with general US data,6,7 the most common genotype was 1a. US-born individuals accounted for all genotypes except 2a/2c and 4, though the number for each of these was low (Figure 1). Individuals from Latin American countries spanned all genotypes except 4, 4a/4c/4d, and 2a/2c, however data again was limited by a small number of patients. The clinic does attend some patients from Egypt, of which five of seven had genotype.4

Although the majority of patients were identified as baby boomers there were still a substantial number of patients who were not a part of this age group, including 25% of the study population that were millennials or generation X (less than 54years old). This implies that, while screening recommendations for individuals born between 1945 and 1965 can detect the largest proportion of patients with C-HCV, there is still a significant demography of patients that can be missed.

This is correlated with the data regarding the route of infection, which demonstrated that a disproportionately large number of patients were believed to have acquired the infection via intravenous drug use. Additionally, approximately 20% of the study population had a comorbid psychiatric disease. Altogether the data suggest that screening for individuals between 1945 and 1965 may miss a significant proportion of patients who are at risk. Accordingly, screening should comprise individuals who engage in behaviour that is high risk for infection with HCV, regardless of age, and that careful assessment of patients with psychiatric comorbidities should be considered in the screening decision as well.

It should be noted that a large proportion of patients had no charted information regarding their ethnicity, birth country, or suspected route of infection. Though this information may not directly guide the clinician’s management of their individual patient, collection of biographical data may provide further key insights and guide the direction of epidemiological and public health studies. Electronic health records can be designed to incorporate templates to capture this information and to improve documentation in these areas.

Treatment data reinforce the efficacy of DAAs.8 The majority of patients achieved SVR at 12 or 24weeks post-treatment. An important number of patients were started on treatment but did not adhere to follow up appointments, which is an ongoing difficulty in the clinic. Eleven out of twelve patients with genotype 3 were successfully treated but one did not return for follow up. Out of sixteen patients with genotype 2a/2c or 2b, twelve were treated successfully but four did not return for follow up. Of the five patients who relapsed after treatment with a DAA, only one was treatment experienced from prior interferon/ribavirin therapy.

A limitation to the study is the number of patients from whom SVR information was not available. Several patients did not adhere to follow up appointments for laboratory RNA testing. The lack of adherence to clinic follow up appears inherent in many clinics where the majority of patients suffer from substance abuse disorder and/or behavioral health disorders. In this context, the establishment of a clinic in behavioral health and methadone clinics to treat patients with C-HCV is a successful model actioned by the authors in another community hospital.9

In conclusion, while current screening guidelines are adequate for detecting baby boomers with C-HCV, there is still a significant number of individuals considered to be Millennials and Generation X with C-HCV who may be missed. As we completed this study, we were pleased to learn that the United States Preventive Services Task Force updated their screening guidelines to include one-time screening for all adults aged 18 to 79years.10 Future screening guidelines may also include individuals with certain comorbidities. Additionally, though the cure rates are high with DAAs, patient adherence to follow up appointments continues to be a limitation, emphasizing the need to expand access to treatment in primary care and behavioral health clinics.

None.

Author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

None.

©2020 Roshan, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.