eISSN: 2373-6372

Case Report Volume 13 Issue 2

Department of Digestive Health and Nutrition, Arnold Palmer Hospital for Children Center for Digestive Health and Nutrition, USA

Correspondence: Akash Pandey MD, Orlando Health, Arnold Palmer Hospital for Children Center for Digestive Health and Nutrition, USA

Received: February 23, 2022 | Published: March 25, 2022

Citation: Pandey A, Boer JA, Melo I, et al. A novel approach for the treatment of lysosomal acid lipase deficiency nonresponsive to conventional therapy regimen. Gastroenterol Hepatol Open Access. 2022;13(2):49-51. DOI: 10.15406/ghoa.2022.13.00493

Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D), or cholesterol ester storage disease, is a rare inherited lipid metabolism disorder affecting the breakdown of cholesterol esters and triglycerides within lysosomes. The case of a 9 year old patient with growth retardation and hepatosplenomegaly had a confirmed diagnosis of LAL-D. The initial response to the recommended Sebelipase alfa enzyme replacement therapy in a biweekly infusion regimen was suboptimal; elevated lipid levels and transaminase elevations continued. After dose escalation by increasing the dose per infusion from 2.2mg/kg to 2.5mg/kg and change from a biweekly to a weekly infusion regimen resulted in significant improvement in the total cholesterol, triglycerides, low density lipoprotein and transaminases. To our knowledge this is the first report in the US on dose escalation and infusion frequency increase in a patient of this age, which resulted in improved short term outcome.

Keywords: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, lysosomal acid lipase deficiency, cholesterol, triglycerides

LAL-D, lysosomal acid lipase deficiency; LIPA, lysosomal acid lipase; CESD, cholesteryl ester storage disease; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

LAL-D is a rare autosomal recessive progressive lysosomal storage disease characterized by deposition of lipids (cholesteryl esters) in different organs, especially the liver, spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow, and vascular endothelium.1 The disease is caused by mutations of the gene encoding lysosomal acid lipase (LIPA).2

Clinical spectrum of LAL-D ranges from milder variant to severe disease that is often referred as Wolman disease which usually presents in infancy and it can lead to early death. Milder disease that is commonly known as cholesteryl ester storage disease [CESD] present in the younger patients and often in adulthood with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. There is gradual decline in the liver function secondary to cholesteryl ester deposition that is often leads to cirrhosis and liver failure. Liver failure is the known cause of mortality in patients with LAL-D.3 Due to its nonspecific clinical features, children after the infant period may need a thorough workup before the diagnosis is established. The disease is often misdiagnosed as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), hereditary dyslipidemia, or cryptogenic cirrhosis.

Early diagnosis and the availability of the enzyme replacement therapy are important to prevent complications. The Sebelipase alfa is a recombinant human lysosomal acid lipase with amino acid sequence identical to that of the human protein. It enters lysosomal compartment by means of the macrophage mannose receptor on reticuloendothelial cells and the M6P receptor.4 Studies have shown that biweekly enzyme replacement infusions result in improvement in the liver function and lipid profile and decreased hepatic fat content.5 Enzyme replacement therapy doesn’t necessarily improve all the complications related to Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency.6

The patient is now a 9-year-old boy, who was initially seen at age 6 with a history of poor weight gain with low IGF level and recurrent epistaxis, who presented with hepatosplenomegaly and mild elevation in the liver enzymes. His initial work-up included a positive ANA (1:640), normal liver autoimmune markers, and no aminoaciduria. He had marked dyslipidemia with total cholesterol of 226mg/dL, LDL 162mg/dL, HDL cholesterol of 44 mg/dL and triglyceride of 90mg/dL. His liver enzymes were elevated [AST 85 U/L, ALT 93 U/L] His abdominal ultrasonography revealed marked hepatosplenomegaly with normal doppler flow. His Lysosomal Acid Lipase activity level was less than <12pmol/hour/μl suggestive of Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency. He had a normal echocardiogram. There was no evidence of esophageal varix on upper endoscopy.

The liver biopsy showed sinusoidal Kupffer cell and portal macrophages with PAS diastase positive material with early bridging fibrosis on trichrome and reticulin stains. No intralobular or portal inflammation were identified. Hepatocytes contained intracytoplasmic glycogen by PAS stain. The biopsy was consistent with Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency.

Genetic testing showed presence of compound heterozygous pathogenic variants of LIPA [coding DNA c.684delt and c894 G>A with variant of p. phe228LeufsX13 and p. Gln298=(q298=).

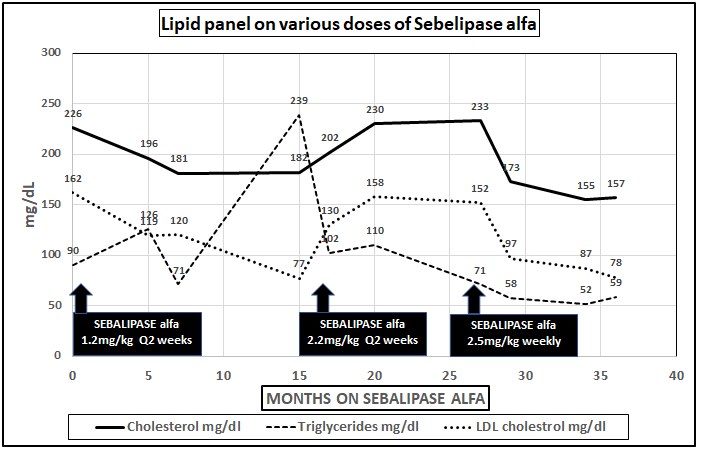

After the diagnosis, detailed dietary recommendations were made to restrict total fat intake and he was started on IV Sebelipase alfa 1.2mg/kg infusion (Kanuma; Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Cheshire, CT, USA) every 2weeks. Initially, mild improvements in liver transaminases and lipid profile were observed with restricted total fat and Sebelipase alfa infusion, but the effect was not lasting despite the compliance with the diet. Dose escalation to 2.2mg/kg biweekly had no clinically significant impact (Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1 Changes in total and LDL cholesterol and triglycerides levels on different dose regimens of Sebelipase alfa.

After 2years on fat restricted diet and standard dose of Sebelipase alfa therapy regimen liver biopsy was obtained. The repeat liver biopsy was similar to the first one and showed portal tracts with preserved lobular architecture with mild bridging fibrosis confirmed by trichrome and reticulin stains. The hepatocytes showed uniform micro vesicular steatosis without individual cell necrosis, intralobular inflammatory infiltrate, macrovesicular steatosis, or cholestasis. The portal tract contained unremarkable bile ducts and vasculature with minimal inflammatory (mainly in lymphocytes) infiltrate. The PAS stain showed prominent intracytoplasmic glycogen. There were rare lipid-laden macrophages. The iron stain was negative.

Abdominal MRI imaging was performed, and it showed hepatosplenomegaly without focal hepatic or splenic lesion. Despite being on standard therapy for 2years, there was no significant histological or biochemical improvement seen.

After the second liver biopsy, while the patient was complaint with the previously recommended dietary changes, he was switched to weekly Sebelipase alfa with dose escalation to 2.5mg per kg/infusion. The only dietary change was that we recommended decreasing saturated fat intake to less than 7% of daily total fat intake with increase in medium chain triglycerides and total protein. Within 2months on this regimen, there was a response with gradual improvement and then normalization in total cholesterol, Low density lipoprotein and triglycerides (Figure 1) and then the liver enzymes [AST and ALT] in 6 months (Figure 2) based on laboratory normative values.

A Sebelipase alfa dose regiment with weekly administration is generally reported in infants with rapidly progressive LAL-D.7 Our patient had abnormal lipid and liver parameters even after 2-year of standard, recommended dose of Sebelipase alfa therapy of 1mg/kg/q2 weeks, but no worsening of the signs and symptoms of LAL-D. After increasing the dose and changing infusion frequency to weekly, first the patient´s serum lipid parameters and then the serum aminotransferases normalized.

Most patients (56/84, 67%) enrolled in the Sebelipase alfa clinical trials were children.8 Children with LAL-D, unlike individuals with metabolic syndrome, may not be obese. Therefore, nonobese patients with liver manifestations may help differentiating LAL-D from other conditions, such as metabolic syndrome. Severe dyslipidemia in a young, lean patient without a family history of cardiovascular diseases or familial hypercholesterolemia also raises suspicion for LAL-D and it should be included in the differential diagnosis in cases of fatty liver disease without signs of metabolic syndrome and in cases of cryptogenic liver disease, dyslipidemia, and hepatosplenomegaly. In 2017 and 2020 consensus reports including experts from multiple specialties were published on the management and monitoring of patients with LAL-D.9,10

In our case the marked improvement in the AST, ALT and lipid profile may indicate a particularly significant alteration of the lipid metabolism improving with weekly infusions and higher dose of Sebelipase alfa. In addition, the further restriction of saturated fat long chain triglycerides also might contribute to these improvements.

This case stresses the importance that in selected cases of LALD, standard recommended dosing and infusion interval of Sebelipase alfa therapy results in sub-optimal treatment outcome. In these selected patients switching to weekly Sebelipase infusion with standard dose may result in greater improvement in aminotransferases and lipid parameters as compared to standard biweekly infusion. This can be explained by short plasma half-life of Sebelipase. Further studies are needed to understand pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of Sebelipase

Parents provided informed consent for publication of the details of this report.

The authors have no conflicts of interest

The authors have not received any funding for the study.

©2022 Pandey, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.