eISSN: 2373-6372

Whipple's disease is a rare chronic disease, multisystem, infectious illness caused by the bacterium Tropheryma whipplei. It is related to an immune defect of the infected individual. It may cause numerous symptoms such as diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal pain, lymphadenopathy, fever, as well as compromise of heart and central nervous system. The diagnosis can be made through laboratory tests, which are not specific to the disease, and by endoscopy and duodenal biopsy. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be performed to confirm the diagnosis in cases where there is relevant clinical features associated with positive tests for the disease. Antibiotics are used for treatment, being Cotrimazol the first drug of choice.

Whipple's disease is a rare chronic infectious disease that affects about 1 in 1,000,000 people annually, being affected mainly Caucasian men aged 40 to 50years.1 Some studies suggest that the occurrence around the world is about approximately 12 new cases/year, though this number certainly represents an underestimate of the total cases.2 It is caused by gram-positive bacterium Tropheryma whipplei. Its etiopathogenesis is linked to a defect of the individual's immunity. There is an impaired activation in the cellular activation and interaction of macrophages with T lymphocytes, causing impaired phagocytosis and no degradation of the bacillus, which is housed in the cell cytoplasm allowing macrophage bacterial dissemination.

It is believed that the intestinal mucosa is the main entrance for the bacteria. Tropheryma whipplei preferably reaches the small intestine at the jejunum level, causing a malabsorption syndrome characterized by diarrhea, weight loss and abdominal pain. Because it is a systemic, infection the patient may present fever, abdominal and peripheral lymphadenopathy. Osteo-articular complaints such as symmetrical oligo- or migratory polyarthralgias of short duration are present in 90% of cases and usually precede the diagnosis in about 10years.3 The central nervous system can also be compromised, which can cause cognitive disorders, myoclonus, hypothalamic changes, seizures, dysphasia, and myelopathy. Other manifestations of the disease can be pericarditis, endocarditis, heart valve abnormality, uveitis, ophthalmoplegia, papilledema, skin hyperpigmentation, pulmonary infiltrates.4

Early diagnosis is difficult to perform because it is a disease with systemic repercussions and nonspecific symptoms. The patient may have microcytic hypochromic anemia, lymphopenia, hypoproteinemia, thrombocytosis, eosinophilia, decreased xylose absorption, reduced folate and vitamin B12. Thus, the specific immediate diagnosis can be performed through endoscopy where there is a thickening of mucosal folds with whitish exudates and mucosal erosions. Histologically, there are infiltrates comprised by macrophages with a granular cytoplasma, showing inclusions which stain positive with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), and phagocytosed bacteria. One can use the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to identify the presence of bacteria in tissue biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.5

The initial treatment for 15 days can be performed with penicillin G and Streptomycin and the long-term treatment for 1 year with trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole or only Cefixime.

JIS, white male, 62, a native of Pernambuco state in Brazil. Patient sought treatment presenting diarrhea, with episodes of bulky stools without blood, mucus or pus for a period of eight months, which was accompanied by weight loss of about 20kg, nausea, vomiting and asthenia. He also complained of polyarthralgia with inflammatory signals.

The physical examination showed a pale and emaciated patient. Blood pressure 100x60mmHg, axillary temperature 36,7˚C. Body Mass Index: 15.07kg/m2. Unremarkable pulmonary and cardiac examination. Abdominal examination without abnormalities apart from the presence of ascites. Bilateral pre-tibial edema.

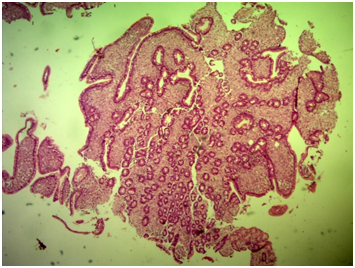

Laboratory tests: Hemoglobin 10mg %, hematocrit 31 %, HIV serology negative. Chest and abdominal CT scans showed bilateral pleural effusions and moderate ascites. Stool search for ova and parasites was negative, and steatocrit was normal. The patient underwent a colonoscopy in which polyps have been found and removed. An upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsies was performed. The histological examination of biopsies showed macrophages with a granular cytoplasma and PAS positive inclusions, compatible with Whipple's disease (Figures 1–4). In the absence of molecular biology test to further confirm the diagnosis, we began treatment with ceftriaxone, with a progressive improvement in the number of bowel movements and the general condition of the patient. After discharge, he continued on sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim for a year. Medication was discontinued after one year and the patient is asymptomatic.

Figure 2 Duodenal mucosa with preserved villous architecture and diffuse infiltrate of macrophages in the lamina propria (HE 40x).

Whipple's disease is a rare disease that affects more men than women, generally in the range from 40 to 50years.6 In Brazil, 15 cases of patients with Whipple 's disease with different clinical manifestations have beenreported in thelast 15years, it shows the rarity of the disease and the difficulty for diagnosis.7–18

The most commonly affected organ is the small intestine. However, the most important symptoms are related to dysfunction of other systems such as skeletal muscle (67%),7 cardiovascular (58%)19 and the central nervous system (10-50%).6,20 It is not known the reason for the damage to the central nervous system in some cases. It may be a result of the development of gastrointestinal dysfunction for years.

Peripheral lymphadenopathy occurs in about 50% of cases.21 There may be a loss of cranial nerves and labyrinth causing hearing loss.22 Polydipsia and polyuria are related to involvement of the pituitary gland and hypothalamus.20

The main differential diagnosis is celiac disease, Crohn's disease, lymphoma, amyloidosis, histoplasmosis. Early diagnosis is difficult because the symptoms are nonspecific and can affect any organ and system. However, early diagnosis is important since the disease is potentially fatal and can cause serious damage to the individual.

Upper endoscopy with intestinal biopsy and PCR, if necessary, are the most effective method of investigation. Endoscopy may show duodenal lesions that disappear with 9 months of treatment with antibiotics.23,24 On the other hand, the PCR technique has a high sensitivity but low specificity, that is, eventually patients without the disease can present a false-positive result. Therefore, PCR is indicated only for people who have the characteristic symptoms of Whipple's disease. In fact, after the introduction of new diagnostic methods, including PCR analysis, there were an increasing number of cases described and published. The presence of macrophages with positive PAS material is not pathognomonic of the disease and can occur in cases of infection with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare, Rhodococcusequi, Bacillus cereus, Corynebacterium, Histoplasma or other fungi, but it is a strong indication of the presence of T. whipplei if associated with other symptoms and tests with positive results. PAS positive macrophages can remain for several years after remission of symptoms, so the positivity of the PAS after treatment may correspond to a false positive and not to relapse or maintenance of the disease.

The treatment is based on antibiotics. Recurrence of disease may occur if patient is not treated properly. There are several treatment regimens based on the severity of the disease and compromised systems, including those using third-generation cephalosporins. Currently, cotrimazol is used as the first choice, 160/800 mg twice daily for one year. If the disease is more severe and affects the central nervous system, intravenous treatment with ceftriaxone 2 g per day for fifteen days with associated streptomycin 1 g is taken up, followed by treatment with Cotrimazol.25,26 Other schemes may be used as 6-24 MU benzathine penicillin intravenously with 1 g streptomycin intramuscularly for two weeks followed by cotrimazol 160/800 mg or third generation cefaslosporina for one year.27 If there is a recurrence with cotrimazol, cefixime 500 mg for one year can be used. The experimental γ interferon along with antibiotic therapy, in patients refractory to antibiotics, resulted in the eradication of bacteria in some cases.28

For some authors, the control of disease progression and prognosis should be carried out from monitoring the patients with the realization of upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsy at 6 and 12 months of treatment.29

The reported patient showed compatible symptoms and additional tests suggesting Whipple's disease, confirmed with endoscopy and biopsies. The improvement with ceftriaxone and later with cotrimazol added further evidence to the diagnosis.

None.

The authors declare there is no conflict of interests.

None.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.