eISSN: 2473-0815

Research Article Volume 3 Issue 3

1Department of Neurological Surgery, Al Assad University Hospital, Damascus University, Syria

2Department of Neurological Surgery, Ohio State University Medical Center, USA

Correspondence: Fawaz Assaad, Professor of Neurosurgery, Damascus University, Syria, Tel 00963 944 2535135

Received: August 03, 2016 | Published: September 16, 2016

Citation: Assaad F, Salma A, Tamer T. Validity of early postoperative random GH level as a predictor factor of long term control of GH- producing pituitary adenoma. Endocrinol Metab Int J. 2016;3(3):58-65. DOI: 10.15406/emij.2016.03.00050

Objective: The aim of this study was to evaluate and to validate the relationship between the

early postoperative basal GH level and the long- term surgical treatment outcome of GH-producing pituitary adenoma as well as to present our experience of treating such types of pituitary adenoma in our institute.

Materials and Methods: We retrospectively analyzed 103 patients with GH-secreting pituitary

adenoma who underwent a surgical treatment between the years 2002 and 2010 in the department of Neurosurgery, University hospital, Damascus.

The basal GH level was measured in the first week after surgery.

With respect to basal GH levels, the patients were assigned to one of three groups:

Group 1: patients with postoperative basal GH levels < 1 ng/mL.

Group 2: patients with postoperative basal GH levels between 1-2.25 ng/mL.

Group 3: patients with postoperative basal GH levels > 2.25 ng/mL.

In every group the hormone activity was monitored postoperatively on a regular basis, the mean follow up duration was approximately 49 months (range 32-96 months). Definitive long term remission of acromegaly was considered to have been achieved when GH levels were less than 1 ng/mL and there was no clinical or magnetic resonance imaging evidence of a persisting disease.

Results: The cure rate in Group 1 was 93.75 %, and in Group 2 was 72.72%, whereas in Group 3

all patients presented evidence of tumor residual or recurrence. The overall rate of cure was 45.23%. There was a significant relationship between the early postoperative basal GH concentration and long- term postoperative outcome (p<0.05).

Conclusion: The early postoperative basal GH level is a simple and reliable factor that may help

with predicting long term surgical outcome of pituitary adenoma.

Keywords: Acromegaly, GH, pituitary adenoma, GH‐producing pituitary adenoma, trans-sphenoidal approach

Acromegaly is a serious systemic condition reported in over 98% of patients with an adenoma of the pituitary gland secreting excessive amounts of growth hormone (GH). GH is a necessary spur for normal linear growth. However, excess secretion of GH induces gigantism in pre-pubertal children, and acromegaly in adults. GH is not the principal stimulator of growth, but it acts indirectly by stimulating the formation of other hormones. These hormones are termed somatomedins Somatomedin C (SM-C), an insulin-like growth factor I [IGF-I]) is the most important SM in postnatal growth. SM-C is produced in the liver, chondrocytes, kidney, muscle, pituitary, and gastrointestinal tract.

The clinical features associated with acromegaly include the effects of GH over secretion and in some instances the tumor directly compressing and injuring the normal pituitary gland, optic nerves and optic chiasm. Untreated acromegaly results in specific bone and soft tissue deformation including an altered facial appearance (frontal bossing, prognathism), enlargement of the hands and feet, sleep apnea, and carpal tunnel syndrome. Severe symptoms include; an accelerated cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and an increased risk of colon cancer. If the tumor develops before bone growth is completed in adolescence, the resulting effect is gigantism.1–6

Because of the serious systemic changes resulting from excess GH, treatment is vital. Trans‐sphenoidal adenectomy has typically been the accepted initial treatment of choice for the majority of patients with Acromegaly.7–17 However, the prediction of postoperative disease activity is a major challenge, and even though different criteria for a cure have been suggested, the relationship between these criteria and long term disease control is not well known.18 –26

The purpose of this is study is to validate the relationship between the early postoperative basal GH level and long term GH level (or in other words, based on GH level early postoperative, what are the chances that the GH will be normalized in long term). We also aim in this report to present our experience of addressing such complicated type of pituitary adenoma.

Patient characteristics

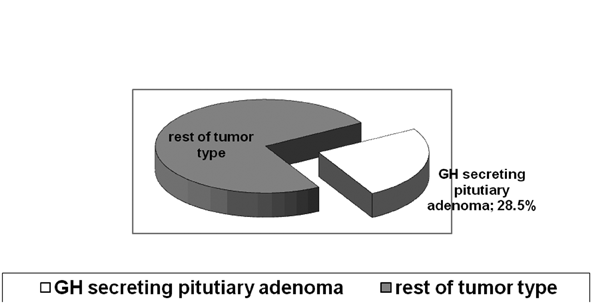

The data of 103 consecutive patients, who underwent a surgical treatment for GH-producing adenomas at the University Hospital in Damascus between 2000 and 2008, were analyzed retrospectively. The patient population consisted of 48 males and 55 females, with a mean age of 39 years (range: 18-60yrs). These patients constituted approximately 28.5% of all cases of pituitary adenoma treated at this location during this period (Figure 1).

All patients had active acromegaly. The diagnosis was confirmed in all cases dependent on the unique clinical picture of acromegaly the patient displayed. Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), we have classified the tumor size as follow; micro <10 mm, meso=10 to 20 mm, macro> 20 mm.27 The titer of basal GH concentration (above 5.0 ng/mL), and a detailed history were obtained from patients pre-operatively, along with a physical examination of neurosurgical, endocrinological, and ophthalmological evaluations. Other baseline hormonal studies were performed (mainly TSH, T3, FT4, Prolactine and Cortisol) before and after operation in all patients.

Surgical procedure

The tumor resection was carried out through a standard sublabial trans-sphenoidal approach in 95 patients 92.2%,28,29 and through frontotemporal craniotomy in 8 patients 7.8%.30,31 All surgical procedures were performed by two experienced neurosurgeon.

Post op GH measurement

GH levels were measured by immunoradiometric assays (IRMA) using a kit from Nichols Institute Diagnostics (San Juan Capistrano, CA), and the following procedures set by the protocol of hormonal assay. The value of basal GH levels was measured in the first week after surgery.

According to this value, the patients were divided into three groups arbitrarily:

Group 1: Patients with early postoperative basal GH levels < 1 ng/mL.

Group 2: Patients with early postoperative basal GH levels between 1-2.25 ng/mL.

Group 3: Patients with early postoperative basal GH > 2.5 ng/mL.

Long term endpoint

The Definitive long- term remission of acromegaly was considered to be present when GH levels were less than 1 ng/mL and there was no clinical or magnetic resonance imaging evidence of a persisting disease.

Statistical analysis

The commercially available SPSS software (Version 16.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used, and the data was analyzed utilizing a chi-square test.

We successfully followed up 84 patients; 19 patients had been excluded due to lost of the follow up. The mean follow up duration was approximately 49 months (range 24-96 months). GH levels were measured within the first week after surgery and at six month intervals thereafter. Magnetic Resonance Imaging studies with and without contrast were done after six months postoperatively and then at twelve months intervals. On the basis of postoperative GH-value, the patients were divided into three groups. The discussion of our results will be based on these groups:

Group 1

Patients with early postoperative basal GH < 1 ng/mL (Table 1).

Follow Up-Period (Month) |

Postoperative Basal GH ng/mL |

Long Term Follow Up |

Size of Tumor |

96 |

0.4ng/mL |

Remission |

Microadenoma |

36 |

0.4ng/mL |

Remission |

Macroadenoma |

24 |

0.5ng/mL |

Remission |

Macroadenoma |

72 |

1.0ng/mL |

Remission |

Microadenoma |

60 |

1.0ng/mL |

Remission |

Microadenoma |

48 |

1.0ng/mL |

Remission |

Microadenoma |

24 |

0.2ng/mL |

Remission |

Microadenoma |

24 |

2.3ng/mL |

Biochemical Recurrence |

Macroadenoma |

74 |

0.8ng/mL |

Remission |

Macroadenoma |

94 |

1.0ng/mL |

Remission |

Microadenoma |

32 |

0.3ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

85 |

0.3ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

36 |

0.7ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

26 |

1.0ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

48 |

0.9ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

24 |

0.24ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

60 |

0.01ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

24 |

1.0ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

48 |

0.7ng/mL |

Remission |

Macroadenoma |

48 |

1.0ng/mL |

Remission |

Macroadenoma |

24 |

0.98ng/mL |

Remission |

Macroadenoma |

36 |

0.57ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

24 |

1.0ng/mL |

Remission |

Microadenoma |

24 |

0.13ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

24 |

1.0ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

26 |

0.1ng/mL |

Remission |

Macroadenoma |

24 |

1.0ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

24 |

0.3ng/mL |

Remission |

Microadenoma |

28 |

1.0ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

24 |

1.9ng/mL |

Biochemical Recurrence |

Macroadenoma |

36 |

0.2ng/mL |

Remission |

Microadenoma |

33 |

0.4ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

Table 1: The detail information of the first group

Consisted of 32 patients, In 30 patients the GH levels did not exceed 1 ng/mL either within the first week after surgery or during the follow- up study. There were no clinical or radiological manifestation of recurrence .In two cases we found biochemical recurrence of acromegaly without clinical or radiological evidence. The cure rate in this group was 93.75% (Figure 2).

Group 2

Patients with early postoperative basal GH between 1-2.25 ng/mL Consisted of 11 patients (Table 2).

Follow Up- Period (Month) |

Postoperative Basal GH ng/mL |

Long Term Follow Up |

Size of Tumor |

60 |

2.25ng/mL |

Recurrence |

Macroadenoma |

24 |

2.5ng/mL |

Remission |

Microadenoma |

36 |

2.24ngmL |

Recurrence |

Macroadenoma |

26 |

2.1ng/mL |

Remission |

Microadenoma |

48 |

1.8ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

48 |

1.7ng/mL |

Remission |

Microadenoma |

48 |

2.0ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

34 |

1.6ng/mL |

Remission |

Macroadenoma |

24 |

1.4ng/mL |

Remission |

Mesoadenoma |

23 |

1.6ng/mL |

Remission |

Macroadenoma |

24 |

2.25ng/mL |

Recurrence |

Macroadenoma |

Table 2: The detail information of the second group

Despite GH level being initially above 1 ng/mL (early follow up study), the GH levels decreased to less than 1 ng/mL in the long-term follow up study in 8 cases (within the first 12 months); and that was associated with no clinical or radiological evidence of recurrence. This yielded a cure rate of 72.72% in this group of patients (Figure 3).

Group 3

Patients with early postoperative basal GH > 2.5 ng/mL (Table 3).

Follow Up- Period (Month) |

Postoperative Basal GH ng/mL |

Size of Tumor |

Treatment Designation |

60 |

8.14ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Repeat Surgery Radiation Therapy+ |

72 |

9.4ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Repeat Surgery Radiation Therapy+ |

72 |

9.6ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Radiation Therapy |

24 |

18ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Radiation Therapy |

34 |

8.2ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Repeat Surgery Radiation Therapy+ |

96 |

10.7ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Repeat Surgery Radiation Therapy+ |

60 |

8.4ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Medical Therapy |

70 |

27ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Repeat Surgery Radiation Therapy+ |

60 |

19ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Repeat Surgery Radiation Therapy+ |

24 |

8.0ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Medical Therapy |

47 |

5.0ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Radiation Therapy |

24 |

36ng/mL |

Mesoadenoma |

Radiation Therapy |

48 |

9.7ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Radiation Therapy |

24 |

12ng/mL |

Mesoadenoma |

Medical Therapy |

45 |

9.1ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Radiation Therapy |

48 |

58ng/mL |

Mesoadenoma |

Repeat Surgery Radiation Therapy+ |

42 |

36ng/mL |

Mesoadenoma |

Radiation Therapy |

48 |

25ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Repeat Surgery Radiation Therapy+ |

34 |

13ng/mL |

Mesoadenoma |

Radiation Therapy |

32 |

8.9ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Radiation Therapy |

38 |

18ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Radiation Therapy |

32 |

16ng/mL |

Microadenoma |

Repeat Surgery Radiation Therapy+ |

33 |

21.5ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Repeat Surgery Radiation Therapy+ |

68 |

15.7ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Repeat Surgery Radiation Therapy+ |

24 |

16.3ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Repeat Surgery Radiation Therapy+ |

24 |

6.6ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Repeat Surgery Radiation Therapy+ |

23 |

Repeat surgery radiation therapy+ |

Macroadenoma |

Radiation Therapy |

28 |

3.9ng/mL |

Mesoadenoma |

Radiation Therapy |

32 |

32ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Radiation Therapy |

24 |

12ng/mL |

Mesoadenoma |

Radiation Therapy |

26 |

9.0ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Medical Therapy |

26 |

8.0ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Medical Therapy |

72 |

6.1ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Medical Therapy |

72 |

5.1ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Medical Therapy |

24 |

6.4ng/mL |

Mesoadenoma |

Medical Therapy |

25 |

7.6ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Repeat Surgery Radiation Therapy+ |

23 |

7.6ng/mL |

Mesoadenoma |

Radiation Therapy |

32 |

7.7ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Medical Therapy |

24 |

5.2ng/mL |

Mesoadenoma |

Medical Therapy |

32 |

6.4ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Repeat Surgery Radiation Therapy+ |

28 |

22ng/mL |

Macroadenoma |

Repeat Surgery Radiation Therapy+ |

Table 3: The detail information of the third group

Consisted of 41 patients. The same procedure of assaying and MRI’s was implemented as had been for the other two groups. Most of the patients in this group had macroadenoma with an adenoma size > 20 mm.

We found in postoperative follow up that 31 cases have high GH- levels associated with radiological evidence of tumor residual or recurrence.

The surgery was repeated in 16 of the 31 patients (followed by radiation therapy), whereas, the remaining 15 patients received radiation therapy directly. In 10 cases a high value of GH levels persisted without radiological evidence. We decided to treat this subgroup with medical therapy alone (Figure 4).

The overall cure rate in the three groups was 38 out of 84 patients (45.23%).

The increased and unregulated growth hormone (GH) production usually is caused by a GH-secreting pituitary tumor in the majority of patients who present with acromegaly clinical picture. However, in very rare occasions, the increased and unregulated GH production is a result of ectopic production of GH and GHRH by malignant tumors.

The clinical picture of acromegaly (its symptoms and signs) develops insidiously, taking years or even decades to become apparent. In addition to the signs and symptoms of acormegaly that produced by the excess production of GH. The excess GH production leads to significant increased in morbidity and mortality additionally, and of course the mass effect of the pituitary tumor itself can cause several problems. Dealing with patients who develop GH producing pituitary adenoma is a challenging medical and surgical task. From surgical prospective, the hormonal functional abnormality is coupled with anatomical deviation making the surgical approach itself is quit more difficult comparing with other types of pituitary adenoma.

The aim of treatment is to control the disease by suppressing GH hyperactivity. More specifically by reducing the size or impeding the growth of the pituitary mass, and eliminating secondary co-morbid complications. The current main treatment options available are; surgery, medical treatment, and radiotherapy. Surgical removal is the main stay treatment for GH secreting adenomas; however, some patients are not cured by surgical treatment alone.

Monitoring disease activity post-operatively is of high priority. Nevertheless, this is not an easy mission, because the criteria to classify as an endocrinological remission are being constantly revised. For instance, in early series, GH levels < 5 ng/mL were used to define biochemical remission. Depending on this criterion, Abosch et al.,32 report that 76% of 254 patients had endocrinological remission after trans-sphenoidal pituitary resection.32

In the same way, Ross and Wils found GH levels < 5 ng/mL in 79% of 165 patients at the 76-month follow-up. However, the basal GH secretion has a pulsatile nature, therefore the GH serum level changes with sleep, age, and nutritional status of a patient.33 For that reason, an assessment of the absolute nadir GH levels (<2 ng/mL) after an oral glucose load was introduced and used by subsequent studies. Using these criteria, Fahlbusch et al.,34 reported a 57% rate of endocrinological remission after trans-sphenoidal surgery. Later, a value of nadir GH levels (GH levels <1 ng/mL) was used as a more conservative criterion.34 Beside GH, an additional criterion for endocrinological remission is the assessment of IGF-I serum levels. This criterion has the following advantage; it reflects integrated 24-hour GH secretion and remains relatively constant over the day. Normalization of IGF-I levels has been demonstrated following the successful treatment of Acromegaly.35–38 However, the interpretation of IGF-I serum levels is more difficult than the interpretation of GH serum level, and the value of IGF-I serum level needs to be adjusted for age and gender.

All in all, normal IGF-I levels and a GH nadir of <1 μg/L after administration of the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) were proposed by a consensus statement in 2000 as criteria for an acromegaly cure. By using this criteria, the endocrinological remission rates range between 57%-67% after microsurgical trans-sphenoidal approaches. However, when considering only pituitary macroadenomas (tumor diameter > 1 cm), Nomikos et al.,39 reported an endocrinological remission in 51% of patients, as well as Beauregard et al.,38

On, 2010, an new consensus came out, this new consensus considers “cure” as IGF-I levels within a normal range and a GH nadir of <1 μg/L or GH levels <0.4 μg/L after OGTT. In a new published study, Hazer et al.,40 found that Random GH levels <2.33 μg/L after the 1st day post operatively is a predictive of cure. Also they found that the GH and IGF-I levels of these “uncured” cases decreased to the hormone levels of the cured cases (GH levels were between 0.4 and 1 g /L) at the 1-year follow-up.

In fact, our findings are consistent with Hazer et al findings. Moreover, we found that with previous criteria the remission can be predicated even for longer follow up period (range 24-96 months).40 There is an important point that Hazer et al pointed out in there article, as they found that using the Strict guideline criteria of 2010 consensus several patients fail to attain a cure in short term according to the 2010 consensus criteria may however they fulfill these criteria in a longer follow-up period. In our current study, we present a retrospective analysis of 103 GH producing pituitary adenoma cases. Having long term postoperative random GH levels to less than 1ng /mL taken at multiple follow up intervals coupled with radiological evidence of total removal of the tumor were the criteria of cure. We depended on random GH level as sole method for laboratory follow up because of its simplicity in addition to some technical issue that prevent us from using the IGF level consentingly in all patients, however, and order overcome the shortage of using the GH level a lone we sampled GH level multiple time randomly.

In group 1, with early postoperative basal GH <1 ng/mL, we found the chance to have GH less than 1 ng/mL in long term was 93.75%. In Group 2, where patients with early postoperative basal GH between 1-2.25 ng/mL, we found we found the chance to have GH less than 1 ng/mL in long term was 72.72% (These patients who fail to attain a cure in short term, have however fulfill these criteria in a longer follow-up period). Our overall cure rate was up to (45.23%) if we take all patient groups together (Figure 5).

For this reason our study validate-at least to some extend-the relationship between the early (in the first week after surgery) postoperative basal GH level and the long term surgical treatment outcome of GH-producing pituitary adenoma. There was a significant relationship between the early postoperative basal GH concentration and long term postoperative outcome (p<0.05). Also, in this study we presents our surgical experience is based on translabial transsphenoidal approach, even though now there is an increase interest in tans nasal endoscopic approach, however we believe, that and especially for GH producing adenoma and because the anatomical deformity the sublabial should be always consider to bypass the tricky nasal anatomical abnormality seen in GH producing pituitary adenoma.

There was a significant relationship between the early postoperative basal GH concentration and long term postoperative outcome (p<0.05). Even in the endoscopic era, classical translabial transsphenoidal is still a power full approach that can be utilized GH-producing adenoma especially when there is significant nasal anatomical deformity.

None.

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

©2016 Assaad, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.