eISSN: 2473-0815

Case Report Volume 13 Issue 1

Medical Student, Latin University of Panama, Faculty of Health and Science, Panama

Correspondence: Medical Student, Latin University of Panama, Faculty of Health and Science, Panama

Received: March 05, 2025 | Published: March 20, 2025

Citation: Olle HK. Familial hypercholesterolemia with alt elevation: a case report. Endocrinol Metab Int J. 2025;13(1):24-26. DOI: 10.15406/emij.2025.13.00365

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is a hereditary condition associated with elevated cardiovascular risk, primarily due to increased LDL levels from a young age. In some cases, total cholesterol and triglycerides are also elevated. This case highlights the variable onset of FH within a family, elevated liver enzymes during statin therapy, and the need for a more aggressive treatment approach. Treatment included dose adjustments of statins and the addition of ezetimibe, with close monitoring for adverse events. Personalized management of FH is essential, balancing the need to control hyperlipidemia and reduce cardiovascular risk against potential liver enzyme elevation from statin therapy.

Keywords: Familial hypercholesterolemia, LDL elevation, cardiovascular risk, statin therapy, liver enzyme elevation, hyperlipidemia management, genetic disorders, dyslipidemia

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is characterized by elevated LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol levels. It is typically inherited as an autosomal dominant disorder caused by mutations in the LDL receptor (LDLR), leading to defective clearance of LDL from circulation. The prevalence of FH is approximately 1 in 500 individuals, with a wide range of clinical presentations. While numerous mutations in LDLR have been identified, other genetic mutations, including APOB, PCSK9, and LDLRAP1, may also contribute to FH.1

Globally, around 10 million individuals are affected by FH, predominantly heterozygotes. Without preventive measures, up to 85% of males and 50% of females with FH may experience a coronary event by the age of 65.2 Clinical diagnosis of FH involves elevated plasma total and LDL cholesterol, a family history of hypercholesterolemia, cholesterol deposits in extravascular tissues such as tendon xanthomas or corneal arcus, and a personal or family history of premature cardiovascular disease (CVD).2 Diagnostic criteria often rely on a weighted combination of physical findings, family history, and circulating LDL-C levels.3 Untreated individuals have a 30-50% risk of a fatal or nonfatal cardiac event by ages 50 and 60 years, respectively.3

Early diagnosis and treatment are critical to reduce cardiovascular risks and prevent premature coronary heart disease or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Individualized treatment plans and close monitoring are essential to optimize outcomes.

Patient information

A 26-year-old male presented with persistently elevated LDL and total cholesterol levels noted during routine laboratory tests. Family history revealed a paternal uncle diagnosed with hyperlipidemia at 19 years old, a maternal uncle diagnosed at 32, and the patient’s mother developing high cholesterol at age 55. The patient’s father and sister remain unaffected.

The patient reported no significant illnesses, maintained an active lifestyle as a collegiate athlete and triathlete, and adhered to a healthy diet. Relevant laboratory findings included:

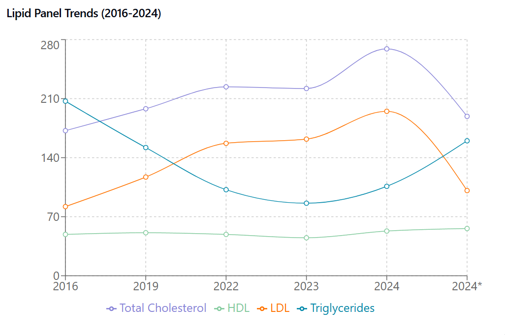

Figure 1 Lipid Panel Trends (2016-2024). Temporal changes in serum lipids before and after statin therapy. Total cholesterol, LDL, HDL (mg/dL) showing marked elevation until statin initiation (*). HDL remained stable throughout. Asterisk indicates post-statin measurements.

Initial treatment with 10 mg of simvastatin resulted in

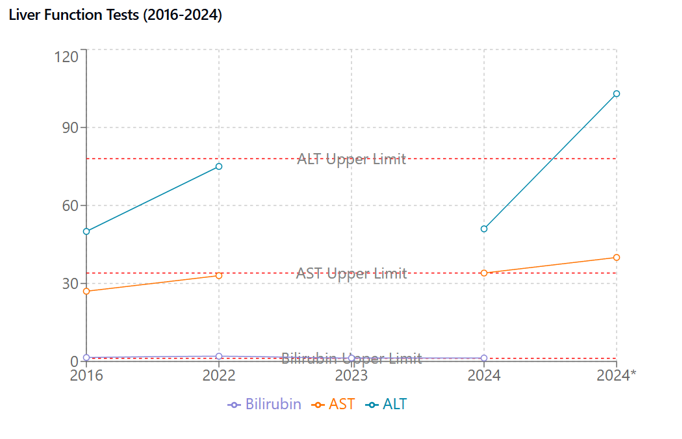

Given the elevated triglycerides and prolonged history of hyperlipidemia, the simvastatin 10mg was changed for rosuvastatin 20mg, and ezetimibe 10 mg was initiated. Due to the elevated ALT and AST, a liver ultrasound and follow-up labs were planned for three months (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Liver Function Tests (2016-2024). Serial measurements of hepatic enzymes and bilirubin. ALT, AST (U/L), and total bilirubin (mg/dL) with reference ranges (dotted lines). ALT shows significant elevation after statin initiation (*). Asterisk indicates post-statin measurements.

Clinical findings

Additional labs

Key clinical findings

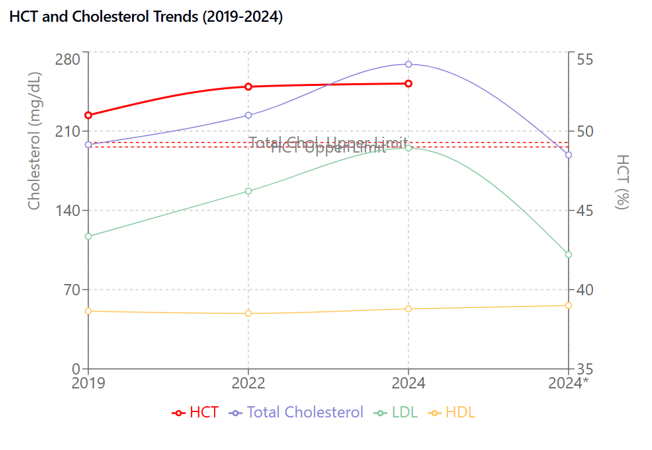

Elevated LDL cholesterol and family history of FH. Post-treatment, ALT and AST elevation were noted (Figure 3).

Figure 3 HCT and Lipid Correlation (2019-2024). Concurrent trends in hematocrit (%, right axis) and lipid parameters (mg/dL, left axis). HCT shows progressive elevation paralleling cholesterol trends. Total cholesterol and LDL decreased after statin therapy (*) while HCT remained elevated. Asterisk indicates post-statin measurements.

Diagnosis of FH relies on various criteria, including the MEDPED, Dutch Lipid Clinic Network (DLCN), and Simon Broome criteria. The American Heart Association (AHA) defines heterozygous FH in adults as LDL >190 mg/dL along with a first-degree relative with premature CVD or a positive genetic test for LDL-C raising mutations.3 For adults over 20 years, the National Lipid Association (NLA) recommends an LDL >190 mg/dL and total cholesterol >220 mg/dL for FH diagnosis.3 While genetic testing is ideal, cost and resource limitations often necessitate clinical diagnosis, particularly in underdeveloped countries. Limited family history knowledge can also pose challenges. The patient was diagnosed with autosomal recessive FH, with possible fatty liver disease or drug-induced liver injury contributing to ALT elevation.

Initial treatment consisted of simvastatin 10 mg daily, resulting in a reduction in LDL to 101 mg/dL. However, ALT increased to 103 U/L. Subsequently:

Treatment adjustments

Follow-up plan

Strengths of case

Limitations

Statin-induced liver enzyme elevation

Statin-induced transaminitis is generally asymptomatic, reversible, and dose-dependent.4 Chalasani5 reported no increased risk of hepatotoxicity in individuals with elevated baseline liver enzymes.

Emerging options

PCSK9 inhibitors and bile acid sequestrants may benefit patients unresponsive to statins and ezetimibe.3

Sex differences and FH

Mulder6 highlighted diagnostic and treatment disparities in women with FH. Li7 found that estrogen suppresses ApoC3 expression, lowering triglycerides, and menopause’s loss of estrogen protection increases cardiovascular risk.8 Lu9 suggested genetic factors and estrogen’s protective effect may influence disease expression in men and postmenopausal women.

Young Adults with Hyperlipidemia: Prolonged hyperlipidemia increases arterial stiffness, emphasizing the need for aggressive prevention and treatment in young adults.10 The patient initially received low-intensity statin therapy (simvastatin 10 mg), later escalated to moderate-intensity treatment. Individualized treatment is crucial, and regular follow-up is necessary to mitigate cardiovascular risk and manage side effects such as ALT elevation.

Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) and its role in liver and cardiovascular health

Recent research has shed light on the importance of Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), a NAD+-dependent deacetylase, in regulating cellular metabolism, aging, and stress responses. SIRT1 has been shown to play a protective role in both liver and cardiovascular health, which is particularly relevant for FH patients who may experience liver enzyme elevation during statin therapy. Zhang11 highlighted that SIRT1-mediated pathways can mitigate oxidative stress and inflammation in liver diseases, suggesting that SIRT1 activation could be beneficial for patients with statin-induced liver enzyme elevation. This finding opens the possibility of exploring SIRT1 activators as a complementary approach to protect liver function in FH patients undergoing statin therapy.11

In the context of cardiovascular health, SIRT1 has been demonstrated to improve endothelial function, reduce oxidative stress, and enhance mitochondrial biogenesis. Kane and Sinclair12 reviewed the role of SIRT1 and NAD+ in metabolic and cardiovascular diseases, emphasizing that SIRT1 activation can improve lipid metabolism and reduce atherosclerosis. These effects are particularly relevant for FH management, as they align with the goals of reducing LDL cholesterol and preventing premature coronary artery disease.12 Similarly, Winnik13 discussed the protective effects of SIRT1 in cardiovascular diseases, suggesting that SIRT1 activators could complement traditional therapies like statins and ezetimibe to further reduce cardiovascular risk in FH patients.13

Patient perspective

The patient expressed concerns regarding lipid levels and liver enzymes but was pleased with the progress in reducing cardiovascular risk. They are committed to maintaining a healthy lifestyle and exercise routine.

This case highlights the importance of individualized treatment in FH management and the need for vigilance regarding potential side effects, such as ALT elevation. Close monitoring and regular follow-ups are essential to optimize long-term outcomes and prevent premature coronary artery disease.

Additionally, given the dual role of SIRT1 in liver and cardiovascular health, dietary interventions or pharmacological agents that enhance SIRT1 activity could be explored as adjunct therapies for FH patients. For instance, SIRT1 activators, such as resveratrol or NAD+ precursors, may help improve liver function while simultaneously reducing cardiovascular risk. This approach could be particularly beneficial for patients who experience statin-induced liver enzyme elevation, as it may provide a protective mechanism against liver damage while optimizing lipid control.

Written consent was obtained from the patient.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

©2025 Olle. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.