eISSN: 2473-0815

Background: Parathyroid carcinoma accounts for 0.5-5% of primary hyperparathyroidism, and is exceptional in Chronic Kidney Disease. It usually presents with Hypercalcemia and increased PTH. Image studies with 99Tc-sestaMIBI scintigraphy and ultrasonography are first line. Histopathological features and negative immunohistochemistry staining for parafibromin provide the definitive diagnosis.

Summary: A 49-year-old male with stage 5 CKD presented with Hypercalcemia and a rapid rise

in PTH levels. Image studies showed signs of parathyroid hyperplasia. After subtotal parathyriodectomy, intraoperative PTH levels did not fall, and a fifth ectopic gland in the mediastinum was resected. Biopsies were consistent with parathyroid carcinoma.

Conclusion: Parathyroid carcinoma is an infrequent pathology in CKD, and should be considered

in patients with sudden rises in calcium and/or PTH levels. Image studies are highly sensitive, but false negatives exist. Unsatisfactory decreases in intraoperative PTH levels suggest an ectopic gland, and may provide the key to a successful surgery.

Keywords: parathyroid carcinoma; chronic kidney failure; hyperparathyroidism; parafibromin; hypercalcemia

PTC, parathyroid carcinoma; CKD, chronic kidney disease; PTH, parathormone; ioPTH, intraoperative PTH; iPTH, intact PTH

Parathyroid carcinoma (PTC) is an infrequent pathology, responsible for 0.5-5% of primary hyperparathyroidism’s.1,2 Despite the high frequency of secondary hyperparathyroidism in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients, PTC is extremely rare, with less than 30 cases reported in the literature.3–5 The diagnosis of PTC is difficult. Usually presents symptoms and signs of Hypercalcemia: fatigue, weight loss, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, polyuria and polydipsia; besides, the patient can present nephrolithiasis, bone pain and fractures. In this context, the presence of a cervical mass or vocal cord paralysis suggests a malignant parathyroid etiology.6 The asymptomatic presentation of PTC is extremely infrequent; however, cases of nonfunctioning PTC have been described.7–8

In laboratory tests, Hypercalcemia and increased parathormone (PTH) are usually found.9–10 Imaging studies of parathyroid lesions often starts with cervical ultrasonography and 99Tc-sestaMIBI scintigraphy; if a PTC is suspected, further imaging with computerized tomography or magnetic resonance is indicated, to determine malignancy characteristics.11–12

Histopathologically, the most widely accepted characteristics to distinguish PTC from other causes of primary hyperparathyroidism are the presence of fibrotic trabeculae, mitotic figures, capsular invasion and vascular permeation.13 As classic histological features are insufficient, immunohistochemistry techniques have been developed to improve this diagnosis.

The study of HRPT2 gene mutations and the expression of its product, parafibromin, have acquired importance, because they are rarely altered in benign parathyroid pathologies.14 Parafibromin is a predominantly nuclear protein that has a role as a tumor suppressor;15 the loss of expression traduced in negative immunostaining is characteristic in PTC. In CKD patients, the diagnosis of PTC is even more complex, as most of the clinical characteristics associated with PTC are also usual manifestations of CKD. It has also been suggested that in this patients, the levels of Hypercalcemia are relatively smaller in comparison of those of PTH.3 Furthermore, the role of parafibromin in this subgroup of patients might not be so clear; in a study on metastatic PTC in CKD, Tominaga Y et al.,16 found positive staining for parafibromin in 7 of 8 examined glands.16

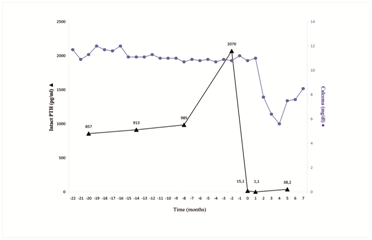

A 49-year-old male with stage 5 CKD of unknown etiology in Hemodialysis for 6 years presented in Endocrine Surgery with high Calcemia and PTH levels during recent controls; last preoperative test was 2.8 mmol/L (11.2 mg/dL) of plasmatic calcium, hyperphosphatemia of 2.45 mmol/L (7.6 mg/dL) and increased PTH (2.287 ng/L). It was striking the rapid rise of PTH level in a few months (Figure 1). No specific symptoms or findings in the physical examination suggesting parathyroid disease were found.

The 99Tc-sestaMIBI scintigraphy showed increased uptake and retention of the tracer near the lower half of the thyroid gland, with normal distribution in the rest of the neck and mediastinum; and was informed as abnormal parathyroid tissue, suggestive of parathyroid hyperplasia, in relation with both thyroid lower poles. With these findings, the patient was hospitalized for a subtotal parathyroidectomy.

During surgery a Subtotal Parathyroidectomy was performed, leaving part of the upper left gland. However, the intraoperative PTH (ioPTH) levels did not decrease as expected, remaining higher than 1,000 ng/L at 15 and 30 minutes after the procedure. Within the same surgical time the patient was re-explored, and a fifth ectopic parathyroid was found in the mediastinum, at the level of the thymus. The gland was resected and sent to intraoperative biopsy, and informed as suspicion of PTC. The ioPTH levels decreased to 180 and 60 ng/L at 15 and 30 minutes after resection, respectively.

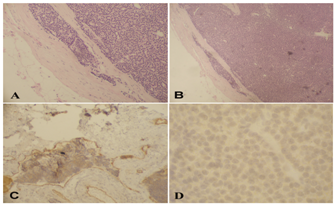

The definitive biopsy of the ectopic gland showed parathyroid tissue without any evident mitotic activity but with focal capsular and vascular invasion, findings compatible with PTC. Immunohistochemical study for parafibromin showed no staining, which was also compatible with the diagnosis. The other glands showed changes suggestive of parathyroid hyperplasia (Figure 2). Staging study with bone scintigraphy and thoracic, abdominal and pelvic computerized tomography’s was negative for metastases. The patient showed a good clinical evolution, and was discharged from the hospital within few days.

The level of intact PTH (iPTH) in mediate postoperative period was 15.1 ng/L, descending to 1.1 ng/L at 1 months of follow up. By the fifth month after surgery, iPTH level rose to 38.2 ng/L, with lower Calcemia levels than before surgery (Figure 1).

As previously described, PTC is a disease of low frequency and difficult diagnosis. In this particular case, additional conditions make the situation even more exceptional. First of all, the PTC was a fifth ectopic parathyroid gland, presenting in the mediastinum. In a literature review by Yong T & Li J17 only 8 of over 700 cases of PTC were Mediastinal;17 interestingly, 2 of them occurred in patients with CKD.]

On the other hand, in this case we described a PTC in the context of end-stage CKD that has a high incidence of secondary and tertiary hyperparathyroidism, but only about 30 cases of PTC have been reported in the literature [4,18]. Many lessons can be extracted from this case report. Classically, secondary hyperparathyroidism in CKD presents with normal or hypocalcemia [19]. In this setting, abnormally high calcium levels and rapid rise of PTH levels should make us suspect a PTC among the differential diagnosis, allowing a focused study and an appropriate surgical planning.

Imaging studies to detect abnormal parathyroid glands have a high sensitivity. Arici C, et al.,12 report sensitivities of 65% and 80% for ultrasonography and 99Tc-sestaMIBI scintigraphy respectively, percentage that rises to 96% when both tests identify a tumor in the same localization.12 In our case the scintigraphy failed to detect the ectopic gland, but did identify two hyper plastic parathyroids. For this reason, the patient must always be evaluated in a comprehensive setting and the surgery must be performed by an experienced team.

Intraoperative PTH measurement with ultra-quick methods has become a fundamental tool in the surgical approach of parathyroid pathologies. As shown in this case, the persistence of high level of the hormone after resection gave the key to searching and finding the ectopic Mediastinal gland, which turned out to be malignant.

Current treatment of PTC is essentially surgical, with en-bloc resection of the tumor and the surrounding compromised tissue,10 including paratracheal lymph nodes (level VI) and ipsilateral thyroid lobe. The management of intramediastinal PTC depends of size, localization and certainty of the intraoperative biopsy. However, the reduced amount of cases reported in the literature does not allow having an established protocol, and every case must be analyzed individually. All glands must be explored, because carcinoma can coexist with adenomas and hyperplasias.20,21 PTC is not considered to be a radiosensitive neoplasm,6 although recent studies have shown some advances with this treatment modality.9 Also, there is no curative chemotherapy, although it is a field of continuous research.22 Other therapeutic resources include the use of bisphosphonates and calcimimetics23 as palliative-symptomatic treatment in patients with recurrence or metastatic disease.

The prognosis of this neoplasm is 69-85% in 5 years.9,24 Follow-up is recommended every 4 to 6 months with laboratory tests, including Calcemia and PTH; if recurrence is suspected, an image study -initially with ultrasonography and scintigraphy-must requested.10 Probably some of these indications may vary in CKD patients, and these tests could be added to routine nephrological controls.

Finally, it must be emphasized that even though PTC in CKD patients is an extremely rare entity, the report of these cases allows the accumulation of experience, which certainly will help to know and manage more effectively this pathology.

None.

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.