Advances in

eISSN: 2373-6402

Research Article Volume 3 Issue 3

Department of Agriculture, Institute of Agricultural Economics, Bulgaria

Correspondence: Hrabrin Bachev, Department of Agriculture, Institute of Agricultural Economics, Bulgaria, Tel 359-246-511-28

Received: February 05, 2016 | Published: April 14, 2016

Citation: Bachev H. On how to define and assess sustainability of farm. Adv Plants Agric Res. 2016;3(3):78-93. DOI: 10.15406/apar.2016.03.00099

This paper suggests a framework for assessing sustainability of farms. It tries to give an answer to two important questions:” what is sustainability of farms? and how to assess farms sustainability?“. Initially, evolution of the “concept” and the major approaches for assessing farm sustainability is discussed and adequate definition is suggested as ability of a particular farm to maintain its governance, economic, social and ecological functions in a long term. After that, a specific example for the conditions of Bulgarian agriculture framework for assessing farm sustainability is proposed including a system of appropriate principles, criteria, indicators, and reference values as well as an approach for their integration and interpretation. The ultimate objective of this study is to work out an effective framework for assessing sustainability of farms in the specific economic, institutional and natural environment of farms of different types and location, assist farm management and strategies, and agricultural policies and forms of public intervention in agriculture.

Keywords: farm sustainability, governance, economic, social, ecological aspects, framework for assessment

Around the globe, the issue of assessment of sustainability of agricultural farms is among the most debated by the researchers, farmers, investors, policy-makers, interest groups, and public at large.1–10 For instance, at the current stage of development of European agriculture the question “what is the level of sustainability of different type of farms during to present programming period of EU CAP implementation?” is very topical.

Despite the enormous progress in the theory and practice in that new evolving area, still there is no consensus on “what is (how to define) sustainability of farm”, “what is relation between the farm and the agrarian sustainability”, and “how to evaluate the sustainability level of agricultural farms” in a dynamic world, where hardly there is anything actually “sustainable”.

In academic publications, official documents and agricultural practices, there is a clear understanding that “farms sustainability and viability” is a condition and an indicator for agrarian sustainability and achievement of sustainable development goals. Also, it is widely accepted that in addition to “pure” production and economic dimensions, the farm sustainability has broader social and ecological aspects, which are equally important and have to be taken into account when measure the overall sustainability level. There are suggestions and use of numerous indicators for assessing agrarian sustainability at “farm level” and approaches are also diverse for their integration and interpretation.

However, most of the assessments of agricultural sustainability are at industry, national or international level,4,7 while, the importance at “farm level” is usually missing. Besides, often the estimates of farms sustainability and agrarian sustainability unjustifiably are equalized. Agrarian sustainability has larger dimensions and in addition to the sustainability of individual farms it includes the importance of individual (type of) farms in the overall resources management and the socio-economic life of households, region and industry and the collective actions of diverse agrarian agents; and the overall (agrarian) utilization of resources and the impacts on natural environment. Further, amelioration of living and working conditions of farmers and farm households, the overall state and development of agriculture and rural households, and overall social governance, food security, and the conservation of agrarian capability, etc. are also included in agrarian sustainability.11

The experience around the globe shows that there are many “highly” sustainable farms contributing little to agrarian sustainability–numerous “semi-market” holdings and subsistence farms, large enterprise based on leased-in lands, public farms etc. in Bulgaria with “low” standards for environmental protection.12 On the other hand, the sustainable agrarian development is commonly associated with the restructuring and adaptation of farms to constantly evolving market, institutional, and natural environment. That process (pre)determines the low sustainability and the diminishing importance of certain type of farms (public, cooperative, small-scale), and the modernization of another part of them by diversification of activity, transformation of family farms into partnerships, firms, vertically-integrated forms, etc. Furthermore, in most cases, a holistic approach is not applied, and aspects of farm development like economic (income, profitability, financial independence etc.), production (land, livestock and labor productivity, eco-conservation technologies etc.), ecological (eco-pressure, harmful emissions, eco-impact etc.), or “social” (social responsibility) are assessed independently of one another. In most of the available frameworks for assessing sustainability level, there is no hierarchical structure or systemic organization of the aspects and the components of farm sustainability, which determines the random selection of sustainability indicators.

Also the critical “governance” functions of the farm, and the costs associated with the governance known popularly as “transaction costs”, and the relations between different aspects of farm sustainability are generally ignored. Nevertheless, very often the level of the managerial (governance) efficiency and the adaptability of farm predetermine the overall level of sustainability independent from the productivity, social or ecological responsibility of activity.2,13 Now, it is broadly recognized that the farm “produces” multiple products, “private” and “public” goods - food, (rural amenities for hunting, tourism, landscape enjoyment), environmental and cultural services, habitat for wild animals and plants, biodiversity, including less desirable ones such as waste, harmful impacts etc. Therefore, all these socio-economic and ecological functions of the farm have to be taken into account when assessing its sustainability. The farm is not only a major production unit but an important governance structure for organization (coordination) of activities and transactions in agriculture, with a great diversity of interests, preferences, goals, skills etc. of participating agents (owners, managers, workers, etc.). Therefore while assessing sustainability and efficiency of different type of farms (subsistent, member oriented, profit making, part-time employment, conservation, etc.) to take also into account their comparative potential in relation to the alternative market, private, public, etc. (including informal) modes of governance of agrarian activity.2,13

In each particular stage of the evolution of individual countries, communities, eco-systems, sub-sectors of agriculture and type of farms, there is a specific knowledge for the agrarian sustainability (e.g. for the links between human activity and climate change), individual and social value system (preferences for “desirable state” and “economic value” of natural resources, biodiversity, human health, preservation of traditions, etc.), institutional structure (rights on food security and safety, good labor conditions, clean nature and biodiversity, of vulnerable groups, producers in developing countries, future generations, animal welfare, etc.), and goals of socio-economic development.

Thus, perception of the agrarian and farm sustainability are always specific for a particular historical period of time and for a particular socio-economic, institutional and natural environment, in which a farm is functioning. For example, many otherwise “sustainable” farms in East Europe were not able to comply with the high EU standards and restrictions for product quality, safety, ecology, animal welfare etc. and consequently entered into “unsustainable” grey sector after the accession of countries to the European Union.

A majority of suggested framework for sustainability assessment apply an “universal” approach for farms, without taking into consideration the specificity of individual holdings (type, resource endowment, specialization, stage of development) and the environment in which they function (competition, institutional support and restrictions, environmental challenges and risks, etc.). What is more, usually most systems cannot be practically used by the farms and managerial bodies, since they are “difficult to understand, calculate, and monitor in everyday activity”.14 This paper suggests a framework for assessing sustainability of farms. First, evolution of the “concept” of farm sustainability and the main approaches for its assessment are analyzed, and on that basis, an attempt is made to define the farm sustainability more precisely. Finally, a system of principles, criteria and indicators for assessing the level of sustainability of farms at the current stage of agrarian development in Bulgarian are proposed. The ultimate objective of this study is to assist farm management and strategies as well as agricultural policies and forms of public intervention in agriculture.

Sustainability as alternative ideology and new strategy

Sustainability movements of farmers and consumers initially emerged in the most developed countries (Switzerland, UK, USA etc.) as a response to concern of particular individuals and groups about negative impacts of agriculture on non-renewable resources and soil degradation, health and environmental effects of chemicals, inequity, declining food quality, decreasing number of farms, decline in self-sufficiency, unfair income distribution, destruction of rural communities, loss of traditional values, etc.15 In that relation the term “sustainable agriculture” is often used as an umbrella term of “new” approaches in comparison to the “conventional” (capital-intensive, large-scale, monoculture, etc.) farming, and includes organic, biological, alternative, ecological, low-input, natural, biodynamical, regenerative, bio-intensive, bio-controlled, ecological, conservative, precision, community supportive etc. agriculture. After that, in the concept of sustainability more topical “social” issues have been incorporated such as: modes of consumption and quality of life; decentralization; community and rural development; gender, intra (“North-South”) and inter-generation equity; preservation of agrarian culture and heritage; improvement of nature; ethical issues like animal welfare, use of GM crop etc.16

For the first time the Rio Earth Summit addressed the global problem of sustainable development and adopted its “universal principles”.10 They comprise rights on healthy and productive life in harmony with nature for every individual, protecting the rights of future generation, integration of environmental, social and economic dimensions at all levels, international cooperation and partnerships , new international trade relations , application of precaution approach in respect to environment , polluter liability, environmental impact assessment, recognition of women, youth, and indigenous role and interests , peace protection, etc. In numerous international forums since 1992, these principles have been specified, amplified and enriched. The last UN Conference on Climate Change in Paris concluded with an agreement to cut emissions and tackle climate change between most (196) countries of the planet.17

The emergence of that “new ideology” has also been associated with a considerable shift of the “traditional understanding” of the development as a theory and policy. In addition to the economic growth, the later now includes a broad range of social, ethical, environment conservation etc. objectives. The modernization of the policies of EU, and diverse international organizations (World Bank, FAO, etc.), and the (national, international) Programs for Agrarian and Rural Development are confirmation of that. In the official documents the general understanding of sustainability is specified and “translated” into language of practice in the form of laws, regulations, instruction, approaches for assessment, system of “good practices” for farmers, etc. Apart from that general (declarative) description of the sustainability, there have also appeared more “operational” definitions for sustainability. For instance, sustainability of farm is often defined as “set of strategies”.18 The managerial approaches that are commonly associated with it are self-sufficiency through use of on-farm or locally available “internal” resources and know how, reduced use or elimination of soluble or synthetic fertilizers, reduced use or elimination of chemical pesticides and substituting integrated pest-management practices, increased or improved use of crop rotation for diversification, soil fertility and pest control; increase or improved use of manures and other organic materials as soil amendments, increased diversity of crop and animal species, reliance of broader set of local crops and local technologies, maintenance of crop or residue cover on the soil, reduction of stocking rates for animals, employment of holistic, life-cycle etc. management of farm and resources, full pricing of agricultural inputs and charges for environmental damages, etc. Accordingly, the level of sustainability of a particular farm is measured through changes in the resources use (e.g. application of chemical fertilizers and pesticides) and the introduction of alternative (sustainable) production methods, and their comparison with the “typical” (mass distributed) farms.

However, interpreting sustainability as “an approach of farming” is not always useful for adequate assessment of sustainability and for “guiding changes in agriculture”. Firstly, strategies and “sustainable practices”, which emerge in response to problems in some developed countries, are not always appropriate for specific conditions of other countries. For instance, a major problem in the Bulgarian farms has been insufficient and/or unbalanced application of N, K, and P chemical fertilizers for higher yield, low rate of farmland utilization and irrigation facility, widespread application of extensive and primitive technologies (insufficient utilization of chemicals, application of too much manual labor and animal force, gravity irrigation), domination of miniature and extensive livestock holdings, etc.19 Apparently, all these problems are quite different from the negative impacts on the natural environment as a result of the over-intensification of farms in the old states of the European Union and other developed countries.

Moreover, the priorities and hierarchy of the goals in a particular country also change in time, which makes that approach unsuitable for comparing sustainability of farms in different subsectors, countries and in different periods. For instance, in EU until 1990s the food security and maximization of output was a main priority, which was replaced after that by the food quality, diversity and safety, conservation and improvement of natural environment and biodiversity; protection of farmers’ income, market orientation and diversification, care for animal welfare and preservation and revitalization of rural communities, etc. Secondly, such understanding of farm sustainability may lead to rejection of some approaches associated with modern farming but nevertheless enhances sustainability. For example, it is well-known that biodiversity and soil fertility are preserved and improved through efficient tillage rather than “zero tillage” and bad stewardship to farmland. Application of such approaches in the past led to enormous challenges and even to loosing of the “agrarian” character of many agro-ecosystems in Bulgaria and other countries alike.10 At the same time, there are many examples for “sustainable intensification” of agriculture in many countries around the world.

Thirdly, such understanding of farm sustainability makes it impossible to evaluate the contribution of a particular strategy to sustainability since that specific approach is already used as a “criterion” for defining sustainability. Fourthly, because of the limited knowledge and information during the implementation of a strategy, it is likely to make errors ignoring some that enhance sustainability or promoting others that threaten long-term sustainability. For examples, the problems associated with the passion on “zero and minimum” tillage in the past in Bulgaria are well-known. Similarly, many experts do not expect a “huge effect” on environmental sustainability from the “greening” of the EU CAP during the new programming period.20

Fifthly, a major shortcoming of that approach is that it totally ignores the economic dimensions (absolute and comparative efficiency of resources utilization), which are critical for determining the level of farm sustainability. It is obvious that even the most ecologically clean farm in the world would not be sustainable “for a long time” if it does not sustain itself economically.

Last but not least important, such an approach does not take into account the impact of other critical (external for the farm) factors, which eventually determine the farm sustainability, namely the institutional environment (existing public standards and restrictions), evolution of markets (level of demand for organic products of farms), macroeconomic conditions (opening up of high paid jobs in other industries), etc. It is well known that the level of sustainability of a particular farm is quite unlike depending on the specific socio-economic and natural environment in which it functions and evolves. For instance, introduction of the support instruments of the EU CAP in Bulgaria (direct payments, export subsidies, Measures of NPARD) increased further sustainability level of large farms and cereal producers, and diminished it considerably for the small-scale holdings, livestock farms, vegetable and fruits producers.21

Furthermore, some negative processes associated with the agrarian sustainability in regional and global scale, could impact “positively” the sustainability of some farms in a particular region or country. Example, focusing on harmful emissions of a particular farm does not make a lot of sense in the conditions of a high overall (industrial) pollution in the region (contrary it will be a greater public tolerance toward farms polluting the environment); global worming increases productivity of certain farms in Bulgaria and other Northern countries since it improves cultivation conditions, reduces the risk of frost, allows product diversification, etc.22

Sustainability as a system characteristic

Another approach characterizes sustainability of agricultural system as “ability to satisfy a diverse set of goals through time”.23-25 The goals generally include: provision of adequate food (food security), economic viability, maintenance or enhancement of natural environment, some level of social welfare, etc. Numerous frameworks for sustainability assessment of farms are suggested which include ecological, economic and social aspects.5,9,26 According to the objectives of the analysis and the possibilities for evaluation, divers and numerous indicators are used for employed resources, activities, impacts, etc.

However, usually there is a “conflict” between different qualitative goals – e.g. between increasing the yields and income from one side, and amelioration of the labor conditions (working hours, quality, safety, remuneration) and negative impact on environment from the other side. There is therefore, a standing question which element of the system is to be sustainable as preference is to be given on one (some) of them on the expense of others. Besides, frequently it is too difficult (expensive or practically impossible) to determine the relation between the farm’s activity and the expected effects – e.g. the contribution of a particular (group of) farms to the climate change.

For resolution of the problem of “measurement” different approaches for the “integration” of indicators in “numeric”, “energy”, “monetary” etc. units are suggested. Nevertheless, all these “convenient” approaches are based on many assumptions associated with the transition of indicators in a single dimension, determining the relative “weight” of different goals, etc. Rarely, the integration of indicators is based on wrong assumptions that the diverse goals are entirely interchangeable and comparable. For instance, the “negative effects from the farming activities” (environmental pollution, negative effects on human health and welfare, etc.) are evaluated in Euros and Dollars, and they are sum up with the “positive effects” (different useful farm products and services) to get the “total effect” of the farm, subsector, etc. Apparently, there is not a social consensus on such “trade-offs” between the amounts of farm products and destroyed biodiversity, the number of sick or dead people etc.

Also it is wrongly interpreted that sustainability of a system is always an algebraic sum of the sustainability levels of its individual components. In fact, often the overall level of sustainability of a particular system-the farm is determined by the level of sustainability of the critical element with the lowest sustainability – e.g. if a farm is financially unsustainable it breaks down. Besides, it is presumed that farm sustainability is an absolute state and can only increase or decrease. Actually, “discrete” state of non-sustainability (e.g. failure, closure, outside take over) is not only feasible, but a common situation in farming around the globe. Another weakness of the described approach is that “subjectivity” of the specification of goals link criteria for sustainability not with the farm itself but with the value of pre-set goals depending on the interests of the and/or stakeholders, the priorities of the development agencies, the standards of the analysts, the understanding of the scientist, etc.). In fact, there is a great variety of (types of) farms as well as preferences of the farmers and farm-owners – e.g. “own supply” with farm products and services; increasing the income or profit of farm households, preservation of the farm and resources for future generations, servicing communities, maximization of benefits and minimization of costs for final consumers, etc.

Besides, at lower levels of the analysis of sustainability (parcel, division, farm, and eco-system) most of the system objectives are exogenous and belong to a larger system(s). For example, satisfying the market demands to low level depends on product of a particular farm or group of farms. Many ecological problems appear on a regional, eco-system, national, transnational or even global scale, etc. Actually, the individual type of farms and agrarian organizations have their own “private” goals namely, profit, income, servicing members, subsistence, lobbying, group or public (scientific, educational, demonstration, ecological, ethical, etc.) benefits. These proper goals rarely coincide with the goals of other systems. At the same time, the extent of achieving all these specific goals is a precondition for the sustainability of the diverse type of organizations of agrarian agents.13

Furthermore, different type of farms like individual, family, cooperative, or corporative have quite dissimilar internal structure, as goals of individual participants not always coincide with the goals of the entire farm. While in the individual and family farm there is a “full” harmony between the owner and farmer ,in more complex farms like partnership, cooperative, or corporation often there is a conflict between the individual and the collective goals. For instance, in Bulgaria and around the globe there are many highly sustainable organizations with a changeable membership of the individual agents (partners, cooperative members, shareholders, etc.).

Therefore, the following question is to be answered: sustainability for whom in the complex social system – the entrepreneurs and the managers of the farm, the working owners of the farm, the farm households, the outside shareholders, the hired labor, the interests groups, the local communities, the society as a whole.

Last but not least important, many of described approaches for understanding and assessing sustainability do not include the essential “time” aspect. However, as rightly Hansen pointed it out: “if the idea for continuation in time is missing, then these goals are something different from sustainability” (Hansen?). The assessment of the sustainability of the farm has to give idea about future, rather than to identify past and present states (the achievement of specific goals in a particular moment of time). For example, the worldwide experience demonstrates that due to the bad management, inefficiency or market orientation of the cooperative and public farms many of their members leave, fail or set up more efficient and sustainable private structures (Bachev, 2010). Simultaneously, many farms with low sustainability in the past are currently with an increasing socio-economic and ecological sustainability as a result of the changes in the ownership, strategy, state policy and support, liberalization and globalization of economies, etc.

Another approach interprets sustainability as an “ability (potential) of the system to maintain or improve its functions”.16,18,24,26 Accordingly, initially main system attributes that influence sustainability are specified as: stability, resilience; survivability; productivity; quality of soil, water, and air; energy efficiency; wildlife habitat; self-sufficiency; quality of life; social justice, social acceptance, etc. After that, indicators for the measurement of these attributes are identified and their time trends evaluated usually for 5-10 and more years. For instance, most often for the productivity indicators such as yield, product quality, profit, income etc. are used. In the Agricultural Economics they are also widespread models for the “integral productivity” of the factors of production (land, labor, capital, innovation).

The biggest advantage of such as approach is that it links sustainability with the system itself and with its ability to function in future. It also gives an operational criterion for sustainability, which provides a basis for identifying constraints and evaluating various ways for improvement. Besides, it is not complicated to quantitatively measure the indicators, their presentation as an index in time, and appropriate interpretation of sustainability level as decreasing, increasing, or unchanged. Since trends represent an aggregate response to several determinant that eliminate the needs to devise complex (and less efficient) aggregation schemes for sustainability indicators.

Above suggested methods however, have significant shortcomings, which are firstly related with the wrong assumption that the future state of the system can be approximated by the past trends. What is more, for newly established structures and farms without previous history that it is impossible to apply that approach for assessing sustainability. However, in most East European countries and in some other regions (Former USSR, China, Vietnam etc.), namely such structures dominate in farming which emerged in the last 10-20 years.

Furthermore, the “reverse ” changes in certain indicators in yield, income, water and air quality, biodiversity, etc. could be result of the “normal” processes of operation of the farm and larger systems, part of which the evaluated farm belongs e.g. the fluctuation of market prices, the natural cycles of climate, the overall pollution as a result of industrial development, etc., without being related with the evolution of sustainability of the farm. For instance, despite environmentally friendly behavior of a particular farm, the ecological state of the farm could be worsening, if needed “collective eco-actions” by all farms in the region are not undertaken.

In order to avoid above mentioned disadvantages, it is suggested to compare the farm indicators not related to specific time, but with the average levels of farms over sub-sector, region etc. However, the positive deviation from the averages not always gives a good indication for the sustainability of farms. There are many cases when all structures in a particular sector and region are unsustainable e.g. dying sectors, uncompetitive productions, “polluting” environment subsectors, deserted regions, financial and economic crisis, etc.. Also there are examples for entire agro-ecosystems, of which the individual “sustainable” farms are a part, they are with a diminishing sustainability or unsustainable as a result of the negative externalities (on waters, soils, air) caused by farms in other regions and/or sectors of the economy, the competition for resources with other industries or uses (tourism, transport, residence construction, natural parks, etc.). In addition, an essential problem of such an approach is that it is frequently impossible to find a single measure for each attribute. The later necessitates some subjective uniformity and prioritizing of the multiple indicators, which is associated with already described difficulties of other approaches for sustainability assessment.

That approach also ignores the institutional and macroeconomic dimensions the unequal goals of different type of farms and organizations and the comparative advantages and the complementarily of the alternative governing structures.12 Namely these factors are crucial when we talk about the (assessment of) sustainability of micro-economic structures like individual and family farms, agro-firms, and agro-cooperatives.

Therefore, sustainability of the individual type of farms cannot be properly understood and assessed without analyzing their comparative production and governance potential to maintain their diverse functions in the specific socio-economic and natural environment in which they operate.2,13

For instance, the high efficiency and sustainability of the small-scale holdings for the part-time employment and subsistence in Bulgaria and East Europe cannot be properly evaluated outside of the analysis of the household and the rural economy. Similarly, the high efficiency of the cooperative farms during the post-communist transition has been caused not by the superior comparative productivity comparing to the family holdings, but on the possibility to organize activities with a high dependency (“assets specificity”) for members in the conditions of a great institutional and economic uncertainty.

As a production and management unit, the sustainability of a particular farm will be determined both from its activity and the managerial decisions like efficiency, ability for adaptation to evolving environment, and the changes in the external environment in market dynamics and crisis, public support and restrictions, extreme climate, etc.. The later are able to significantly improve or deteriorate the sustainability of individual farms, independence of the management decisions of the individual holdings. Example, direct subsidies from the EU have increased considerably the sustainability of many previously less sustainable Bulgarian farms.27

Finally, there exists no individual farm or any other system, which is sustainable “forever”. Therefore, the assessment of the “sustainability” of the farm is also associated with the answer to the question for how long and for what period of time we are talking about?

Considering the constant evolution of the features and the concept of sustainability from one side, and the evolution of the entire agrarian system from the other side, the sustainability is increasingly perceived “as a process of understanding of changes and adaptation to these changes” (Raman). According to that new understanding, the agrarian or farm sustainability is always specific in time, situation, and component, and characterizes the potential of agricultural systems to exist and evolve through adaptation to and incorporation of the changes in time and space. For example, in the current stage of the development respecting the “rights” of farm livestock and wild animals (“animal welfare”) is a substantial attribute of the farm sustainability.

Moreover, the incorporated internal dynamisms of the system also implies an “end life” (there is no system which is sustainable forever) as a particular agrarian system is considered to be sustainable if it achieves (realizes) its “expected lifespan”. For instance, if due to the augmentation of the income of the farm households the number of subsistence and part-time farms is decreasing while the agrarian resources and effectively transferred to other (novel, larger) structures, this process should not be associated with a negative change in the sustainability of farms in the region or subsector. On the other hand, if a particular farm is not able to adapt to the dynamic economic, institutional and climate changes through adequate modernization in technology, product, and organization, it is to be evaluated as low sustainable.

The characterization of sustainability has to be “system-oriented” while the system is to be clearly specified, including its time and spatial boundaries, components, functions, goals, and importance in the hierarchy. That implies taking into account the diverse functions of the agricultural farms at the current stage of development as well as the type and efficiency of the farm, and its links (importance, dependency, complementarily) with the sustainability (economy) of the households, the agrarian organizations, the region, the eco-system and the entire sectors (industry).

The sustainability has to reflect both the internal capability of the farm to function and adapt to environment as well as the external impact of constantly evolving socio-economic and natural environment on the operation of the individual farm. However, it is to be well distinguished the features of relatively independent (sub) systems – e.g. While the “satisfaction from farming activity” is an important social attribute of the farm sustainability, the modernization of the social infrastructure and services in rural areas is merely a prerequisite (factor) for the long-term sustainability of the individual farm.

Furthermore, the sustainability approach is to allow a comparative analysis of the diverse agricultural systems – e.g. farms of different type and kind in the country, farms in different countries, etc. Thus all approaches, which associate comparability only with the “continues (quantitative) rather than discrete property” of a system9,24 are to be rejected. In fact, there is no reason to believe that the sustainability of an agricultural system could only increase or decrease. Discrete features (“sustainable”-“non-sustainable”) are possible, and of importance for the farm managers, interests groups, policy makers.2

Characterization of the sustainability must also be predictive since it deals with future changes rather than the past and only the present. And finally, it should be diagnostic, and to focus intervention by identifying and prioritizing constraints, testing hypothesis, and permitting assessments in a comprehensive way.

In addition, the sustainability has to be a criterion for the guiding changes in policies, and farming and consumption practices, agents’ behavior, for focusing of research and development priorities, etc. In that sense, analysis of the levels and the factors of “historical” sustainability of farms (the “achieved level of sustainability”) in a region, subsector, other countries, etc. are extremely useful for the theory and practice. The assessments of the past states help us both to precise the approach and the system and importance of sustainability indicators as well as identify critical factors and trends of the sustainability level of farms. On the later base, efficient measures could be undertaken by the managers, state authority, stakeholders etc. for increasing the current and the future level through education, direct support, innovation, restructuring, partnerships, etc.

Last but to least important, the sustainability is to allow facile and rapid diagnostic, and possibility for intervention through identification and prioritizing of restrictions, testing hypothesis, and giving possibility for comprehensive assessments. The later suggests that the sustainability concept and assessment is easy to understand and practical to use by the agents without evaluation to require huge costs (economic “justification” of undertaking assessment or increasing its precision).

Accordingly it is to be worked out a system of adequate principles, criteria, and indicators for assessing the individual aspects and the overall level of sustainability of the farms in the specific conditions of each country, particular subsector, region, ecosystem, etc. Each of the elements of such a hierarchical system is to meet certain conditions (criteria) like: discriminating power in time and space, analytical soundness, measurability, transparency, policy relevance, transferability for all type of farms, relevance to sustainability issue, etc.9

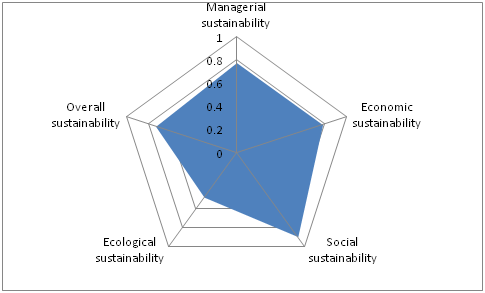

For instance, in Bulgaria, like in many other countries, there is no such an “issue” nor any institutional restrictions (norms) exists, and when an assessment of the farm sustainability is performed it is not important to include the “contribution” to the greenhouse gas emission of the livestock and machineries . At the same time, the number of animals on unit of farmland is of critical importance since the underutilization or over-exploitation of pastures as well as the mode of storing and utilization of the manure is critical for the sustainable exploitation of natural resources in the country. The definition of the sustainability of the farm has to be based on the “literal” meaning of that term and perceived as a system characteristics and “ability to continue through time”. It has to characterize all major aspects of the activity of a farm, which is to be managerially sustainable, and economically sustainable, and ecologically sustainable, and socially sustainable (Figure 1).

Therefore, the farm sustainability characterizes the ability (internal potential, incentives, comparative advantages, importance, and efficiency) of a particular farm to maintain its governance, economic, ecological and social functions in a long-term.

A farm is sustainable if:

The assessment of the sustainability of the farms has to be always made in the specific socio-economic, ecological, etc. rather than an unrealistic (desirable, “normative”, ideal) context. In that sense, the employment of any “Nirvana approach” for determining the criteria for the sustainability (not related to the specific environment of the farm “scientific” norms of agro-techniques; a model of farming in other regions or countries; assumptions of perfectly defined and enforced property rights and institutional restrictions; an effectively working state administration; a situation without missing markets and public interventions, etc.) is not correct.

Taking into account of the external socio-economic and natural factors let also identify the major factors, which contribute to the sustainability of a particular farm – e.g. competitiveness, adaptability, evolution of farmers and agrarian organizations, access to public programs, level of state support, institutional environment, extreme climate, plant and livestock diseases, etc.

In a long-term there exists no economic organization if it is not efficient otherwise it would be replaced by more efficient organization.13 Therefore, the problem of assessment of the sustainability of the farms is directly related to the assessment of the levels of governance, production and ecological efficiency of farms.

In addition, it has to be estimated the potential of the farm for adaptation to the evolving market, economic, institutional, and natural environment through effective changes in the governing forms, size, production structure, technologies, behavior, etc. If the farm does not have potential to stay at or adapt to a new more sustainable level(s) it will diminish its comparative efficiency and sustainability, and eventually would be either liquidated or transformed into another type of organization.2,4

For instance, if a particular farm faces enormous difficulties meeting institutional norms and restrictions (e.g. new quality and environmental standards of the EU; higher novel social norms; new demands of rural communities, etc.) and taking advantage from the institutional opportunities (access to public subsidies and support programs); or it has serious problems supplying managerial capital (as it is in a one-person farm when an aged farmer does not have a successor), or in supply of needed farmland (a big demand for lands from other agrarian entrepreneurs or for non-agricultural use), or funding activities (insufficient own finance, impossibility to sell equity or buy a credit), or marketing output and services (changing demands for certain products or needs of cooperative members, a strong competition with imported products); or it is not able to adapt to existing ecological challenges and risks (e.g. weather warming, extreme climate, soils acidification, water pollution, etc.), then it would not be sustainable despite the high historical or current efficiency. Therefore, the adaptability of the farm characterizes to a greater extend the farm sustainability and has to be used as a main criteria and an indicator for sustainability assessment.

Major definitions

Agricultural Farm (Farm): The farm is the main organizationally independent production and management unit in agriculture, which produce agricultural products and services (food for humans and animals, raw materials for processing, bio-energy, agro-ecosystem services, etc.) and/or maintain agricultural lands in a good agricultural and ecological state. The production of diverse agricultural products and services, and the organizational and the managerial apartness (autonomy) are essential criteria for the identification of the farm. Accordingly, a farm could be diversified in many productions and located in many areas, if it is managed by a single farmer. A particular entrepreneur may have several farms (e.g. an own farm and participation in a partnership, for organic and conventional production, etc.), which are separately registered and managed. A particular farm may not be entirely independent if it is a part of a vertically or horizontally integrated organization (ownership) – e.g. a part of the overall activity of a family firm, a cooperative, a research or educational institution, a division of the processing enterprise, restaurant, and retailer of exporter.

Sustainability of the farm: Farm sustainability characterizes the ability (internal capability) of a particular farm to exist in time and maintain in a long-term its governance, economic, ecological and social functions in the specific socio-economic and natural environment in which it operates and evolves.

Aspects of farm’s sustainability

Sustainability of the farm has four aspects, which are equally important and have to be always accounted:

- managerial sustainability – the farm has to have a good or high absolute and comparative efficiency for the organization of its activity and (internal and external) relations, and a high adaptability to evolving socio-economic and natural environment, according to the specific preferences (type of the farm, character of production, long-term goals, etc.) and capability (training, experience, available resources, connections, power positions, etc.) of the owners of the farm;

Levels of sustainability assessment

The assessment of the sustainability of the farms could (is to) be done at different levels:

The assessments at higher economic and special levels are aggregate of the assessment of the individual farms.For a rapid diagnostic of the farm sustainability at higher levels may be also used a system of selected (farm level or aggregated) indicators, which adequately reflect the major aspects of the sustainability of individual holdings. For instance, level of N pollution in the ground waters in a region (ecosystem) could give a good insight on ecological sustainability of the farms in that region (ecosystem).

It is also necessary to estimate the importance of different (kind and type of) farms in the overall resources utilization, total agricultural output, social and economic life, impacts on environment, etc. of relevant ecosystems, regions, subsectors, and agriculture as a whole. The later “determines” the link of the sustainability of the farms with the agrarian sustainability, and makes it possible to take decisions for improving public policies and strategies of farms and agrarian organizations for sustainable development

Farms classification

The level of the sustainability of farms and their contribution to the agrarian sustainability usually depends on the farms’ type and kind. The later requires classification of the farms according to a number of criteria.

The major types of farms according to the juridical status (forma registration) in Bulgarian are: Physical Person, Sole Trader, Corporation, and Cooperative, specified by the national legislation. Furthermore, they are forms with an open, close, mixed, publicly traded etc. membership.

According to the type of ownership, the farms could be private, state, municipal, community, public, local, foreign, and hybrid. According to the economic and managerial autonomy there are (totally) independent, horizontally integrated and vertically integrated holdings. According to the market orientation the farms are: subsistence holdings and farms for servicing of members, “semi-market” farms, commercial farms, and business enterprises. According to their size the agricultural farms are: small scale, middle sized, and large as different criteria could be used to classify them for this indication – the size of managed land, number of grazed livestock, number of employed labor, gross income, “economic size” etc. According to the production specialization the farms in the country are classified in more or less aggregated groups: crop production (field crops, horticulture, permanent crops, etc.), livestock production (grazing livestock, pigs, poultry and rabbits, etc.). Mixed production (mixed crops, mixed livestock, mixed crop-livestock, etc.). According to the ecological orientation and certification the farms are: with organic certification or in a transition period to organic certification, with conventional production, with ecological production, with mixed production, etc.

According to the special private or social objectives the farms could be: experimental, demonstrative, educational, conservation and recovery of traditional breeds of livestock or varieties of crops, protected and/or certified origins, products, services etc. According to the location the farms are classified in different groups depending on which ecosystems they include or are part of (plain, mountainous, semi-mountainous, riverside, seaside, protected zoned and natural reserves, with high risk, etc.), and/or which administrative (region, municipality, country), geographical (border, North Bulgaria, etc.) or social and economic (well developed, developing, underdeveloped, unpopulated, declining activity) regions they are located in.

Taking into account of “time factor”

The assessment of the sustainability of the farms always is done in a specific historical moment of time (a certain date), which inevitably reflects the existing specific knowledge and preferences for the state of the farms and its impacts, the possibilities to identify, monitor, measure, and evaluate the different aspects of the sustainability and impacts of the farms, the available information and access to the first hand data from the farms, the needs of the farms’ managers and agrarian policy, etc. in that particular moment (period) of time.

For the assessment of many of the dimensions of sustainability of the farms it is to be used (averaged) annual or multiannual data. That is required by the needs to eliminate the big variations of levels of the snapshot states (data, moment “picture”) result of the “natural” economic, investment, agronomic, biological or climate cycles (e.g. profitability, financial liability, productivity, number of livestock, inputs of chemicals, volume of irrigation, crop rotation, etc.) or unavailability of another report, statistical, accountancy, first hand etc. information.

Two type of the assessment of the sustainability of the farm have to be distinguished:

Moreover, it is to be distinguished and made assessment on the short-term, mid-term and long-term sustainability of the farms. Often the sustainability of the farm is changeable in time, which necessitates the estimation of the realized or likely level for a particular (practical) horizon of time:

The hierarchical levels, which facilitate the formulation of the system for assessing the sustainability of the farms, include well determined and selected principles, criteria, indicators and reference values (Figure 2).

Source: adapted by the author from Sauvenier et al.9,28-30

Principles – the highest hierarchical level associated with the multiple functions of the agricultural farms. They are universal and represent the states of the sustainability, which are to be achieved in the four main aspects – managerial, economic, social and ecological. For instance, a Principle “the soil fertility is maintained or improved” in the Ecological aspect of the farm sustainability. Criteria – they are more precise from the principles and easily linked with the sustainability indicators. They represent a resulting state of the evaluated farm when the relevant principle is realized. For instance, a Criteria “soil erosion is minimized” for the Principle “the soil fertility is maintained or improved”.

Indicators – quantitative and qualitative variables of different type (behavior, activity, input, effect, impact, etc.), which can be assessed in the specific conditions of the evaluated farms, and allow to measure the compliance with a particular criteria. The set of indicators is to provide a representative picture for the farm sustainability in all its aspects. For instance, an Indicator “the extent of application of good agro-technics and crop rotation” for the Criteria “soil erosion is minimized”.

Reference value – these are the desirable levels (absolute, relative, qualitative, etc.) for each indicator for the specific conditions of the evaluated farms. They assist the assessment of the sustainability level and give guidance for achieving (maintaining, improving) sustainability of the farm. They are determined by the science, experimentation, statistical, legislative or other appropriate ways.

As a Reference value it could be used:

Most of the Reference values show the level, which (presume to) guarantee the long-term farm sustainability. Depending on what extent it is achieved or overcome the farms could be with a high, good, or low sustainability, or to be unsustainable. For instance, the farms with higher than the average for the sector profitability or lower soils’ acidity are more sustainable then others, while farms with accordingly inferior or greater values are with lower economic or ecological sustainability or (economically, ecologically) unsustainable.31-33 Another part of the Reference values characterizes a condition for the sustainability, deviation of which indicates the state of insufficient sustainability or unsustainability. For instance, the farms not complying with the official standards for labor (working, safety etc.) conditions, animal welfare, application of banned chemicals and technologies, producing forbidden products (cannabis) etc;

The content and the importance of the principles, criteria, indicators and reference values are formulated/selected by the leading experts on farm sustainability. Moreover, they have to be permanently updated for the specific conditions of evaluated farms and according to the development of science, measurement and monitoring methods, available information, industry standards, social norms, etc. We have profoundly studied out the available academic publications, official documents, and experiences in Bulgaria and other countries as well as carried our numerous consultations with the leading national and international experts in the area. On that base we have prepared a list (system) with potential principles, criteria, indicators and reference values for the contemporary conditions of Bulgarian farms.

After that we organized a special expertise with ten leading scholars working on the sustainability of the farms from the Institute of Agricultural Economics and the University of National and World Economy in Sofia, and the Agrarian University in Plovdiv. The experts discussed, complemented and evaluated the importance of the suggested by us principles, criteria, indicators and reference values, and selected the most adequate ones for the contemporary conditions of the development of Bulgarian farms (Table 1).

Principles |

Criteria |

Indicators |

Reference values |

|

Governance Aspect |

||||

Acceptable governance efficiency |

Efficiency for governing of activity in relation to other feasible organization |

Comparative efficiency for supply and management of workforce |

Similar to alternative organization |

|

Comparative efficiency for supply and management of workforce of natural resources |

Similar to alternative organization |

|||

Comparative efficiency for supply and management of material inputs |

Similar to alternative organization |

|||

Comparative efficiency for supply and management of innovations |

Similar to alternative organization |

|||

Comparative efficiency for marketing of products |

Similar to alternative organization |

|||

Comparative efficiency for supply and management of finance |

Similar to alternative organization |

|||

Sufficient adaptability |

Farm adaptability |

Level of adaptability to market environment |

Good |

|

Level of adaptability to institutional environment |

Good |

|||

Level of adaptability to natural environment |

Good |

|||

Economic Aspect |

||||

High economic efficiency |

Economic efficiency of resource utilization |

Level of labor productivity |

Similar to the average for the sector |

|

Land productivity |

Similar to the average for the sector |

|||

Livestock productivity |

Similar to the average for the sector |

|||

Economic efficiency of activity |

Profitability of production |

Similar to the average for the sector |

||

Farm Income |

Acceptable by the owner |

|||

Good financial stability |

Financial capability |

Return on own capital |

Average for the sector |

|

Overall Liquidity |

Average for the sector |

|||

Financial autonomy |

Average for the sector |

|||

Social Aspect |

||||

Good social efficiency for farmer and farm households |

Farmers welfare |

Income per a member of farm household |

Similar to other sectors in the region |

|

Satisfaction of activity |

Acceptable for the farmer |

|||

Working conditions |

Compliance with formal requirements for working conditions |

Standards for working conditions in the sector |

||

Acceptable social efficiency for not farmers |

Preservation of rural communities |

The extent farm contributes to preservation of rural communities |

Overall actual contribution |

|

|

Preservation of traditions |

The extent farm contributes to preservation of traditions |

Overall actual contribution |

|

Ecological Aspect |

||||

Protection of agricultural lands |

Chemical quality of soils |

Soil organic content |

Similar to the typical for the region |

|

Soil acidity |

Similar to the average for the region |

|||

Soil soltification |

Similar to the average for the region |

|||

Soil erosion |

Extent of wind erosion |

Similar to the typical for the region |

||

Extent of water erosion |

Similar to the typical for the region |

|||

Agro-technique |

Crop rotation |

Scientifically recommended for the region |

||

Number of livestock per ha |

Within limits of acceptable number |

|||

Rate of N fertilization |

Within limits of acceptable amount |

|||

Rate of K fertilization |

Within limits of acceptable amount |

|||

Rate of P fertilization |

Within limits of acceptable amount |

|||

Extent of application of Good Agricultural Practices |

Approved rules |

|||

Waste management |

Manure storage type |

Rules for manure storage |

||

Water irrigation |

Irrigation rate |

Scientifically recommended rate for the region |

||

Protection of waters |

Quality of surface waters |

Nitrate content in surface waters |

Similar to the average for the region |

|

Pesticide content in surface waters |

Similar to the average for the region |

|||

Quality of ground waters |

Nitrate content in ground waters |

Similar to the average for the region |

||

Pesticide content in ground waters |

Similar to the average for the region |

|||

Protection of air |

Air quality |

Extent of air pollution |

Acceptance from rural community |

|

Protection of biodiversity |

Variety of cultural species |

Number of cultural species |

Similar to the average for the region |

|

Variety of wild species |

Number of wild species |

Similar to the average for the region |

||

Animal welfare |

Norms for animal welfare |

Extent of compliance with animal welfare norm |

Standards for animal breeding |

|

Preservation of ecosystem services |

Quality of ecosystem service |

Extent of preservation of ecosystem services |

Acceptance from communities |

|

Table 1 Principles, criteria, indicators and reference values for assessing sustainability of farms in Bulgaria

For the selection of the indicators for the sustainability assessment a number of criteria have been used which are relevant to reflect sustainability aspects, discriminating power in time and space, analytical soundness, intelligibility and synonymy, measurability, governance and policy relevance, and practical applicability. The goal was to select a balanced (around a half for the governance, economic and social aspects, and the rest for the ecological aspect) system with sufficient (1-5 for each criteria), but not too many indicators (not more than 50), which would guarantee the efficiency of use.

Calculation, presentation, interpretation and integration of assessments

For assessing the sustainability level of individual farms it is necessary to use firsthand information provided by the farm managers, available reports and statistical information, experts assessment by the professionals in the area, etc. Often there are a number of different ways for calculating the level of each particular indicator. For instance, the Profitability of Production of the farm may be calculated by dividing the Net Agricultural Income, the Gross Agricultural Profit, the Profit After Tax etc. to the Total Agricultural Costs, the Current (Overall, Agricultural) Costs, the Variable (Overall, Agricultural) Costs etc. It is the same for most of other governance, economic, social and ecological indicators. It is important always to use similar approach for calculating all sustainability indicators. The same approach applies for the Reference Values employed in the sustainability assessment.

Next, qualitative or quantitative value of every indicator is to be determined and compared with the Relevant Reference Value. A level of a particular indicator on, within or close to the Reference Value(s) means a good or high sustainability, and vice versa. Indicators which are not appropriate for a particular farm are to be excluded e.g. “compliance with animal welfare norms” for holdings without livestock activity, “preservation of rural communities” for a single and remote from the residence areas high mountainous farm(s), etc. Usually there is a “state of sustainability” of the farm with different values of a particular indicator. Thus the level of the sustainability is to be specified. Experts will be instructed to determine different qualitative states of the sustainability (high, good, low, insufficient, none) for diverse deviations of the indicators values from the Reference values (Table 2).

Indicators |

Reference value (RV) |

Levels of sustainability |

Non |

|||

High |

Good |

Low |

Insufficient |

sustainable |

||

1.Comparative efficiency for supply and management of workforce |

Similar to alternative organization |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

2. Comparative efficiency for supply and management of natural resources |

Similar to alternative organization |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

3. Comparative efficiency for supply and management of material inputs |

Similar to alternative organization |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

4. Comparative efficiency for supply and management of innovations |

Similar to alternative organization |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

5. Comparative efficiency for marketing of products |

Similar to alternative organization |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

6. Comparative efficiency for supply and management of finance |

Similar to alternative organization |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

7. Level of adaptability To market environment |

Good |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

8. Level of adaptability to institutional environment |

Good |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

9. Level of adaptability to natural environment |

Good |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

10. Level of labor productivity |

Similar to the average for the sector |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

11. Land productivity |

Similar to the average for the sector |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

12. Livestock productivity |

Similar to the average for the sector |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

13. Profitability of production |

Similar to the average for the sector |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

14. Farm Income |

Acceptable by the owner |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

15. Return on own capital. |

Average for the sector |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

16. Overall Liquidity |

Average for the sector |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

17. Financial autonomy |

Average for the sector |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

18. Income per a member of farm household |

Similar to other sectors in the region |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

19. Satisfaction of activity |

Acceptable for the farmer |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

20. Compliance with formal requirements for working conditions |

Standards for working conditions in the sector |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

21. The extent farm contributes to preservation of rural communities |

Overall actual contribution |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

22. The extent farm contributes to preservation of traditions |

Overall actual contribution |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

23. Soil organic content |

Similar to the typical forthe region |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

24. Soil acidity |

Similar to the average for the region |

<RV |

= RV |

> RV |

>>RV |

>>>RV |

25. Soil soltification |

Similar to the average for the region |

<RV |

= RV |

> RV |

>>RV |

>>>RV |

26. Extent of wind erosion |

Similar to the typical for the region |

<RV |

= RV |

> RV |

>>RV |

>>>RV |

27. Extent of water erosion |

Similar to the typical for the region |

<RV |

= RV |

> RV |

>>RV |

>>>RV |

28. Crop rotation |

Scientifically recommended for the region |

= RV |

> RV |

>>RV |

>>>RV |

>>>>RV |

29. Number of livestock per ha |

Within limits of acceptable number |

= RV |

> RV< |

>>RV<< |

>>>RV<<< |

>>>>RV<<<< |

30. Rate of N fertilization |

Within limits of acceptable amount |

= RV |

> RV< |

>>RV<< |

>>>RV<<< |

>>>>RV<<<< |

31. Rate of K fertilization |

Within limits of acceptable amount |

= RV |

> RV< |

>>RV<< |

>>>RV<<< |

>>>>RV<<<< |

32. Rate of P fertilization |

Within limits of acceptable amount |

= RV |

> RV< |

>>RV<< |

>>>RV<<< |

>>>>RV<<<< |

33. Extent of application of Good Agricultural Practices |

Approved rules |

= RV |

> RV |

>>RV |

>>>RV |

>>>>RV |

34. Manure storage type |

Rules for manure storage |

= RV |

> RV |

>>RV |

>>>RV |

>>>>RV |

35. Irrigation rate |

Scientifically recommended rate for the region |

= RV |

> RV< |

>>RV<< |

>>>RV<<< |

>>>>RV<<<< |

36. Nitrate content in surface waters |

Similar to the average for the region |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

37. Pesticide content in surface waters |

Similar to the average for the region |

>RV |

= RV |

< RCV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

38. Nitrate content in ground waters |

Similar to the average for the region |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

39. Pesticide content in ground waters |

Similar to the average for the region |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

40. Extent of air pollution |

Acceptance from rural community |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

41. Number of cultural species |

Similar to the average for the region |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

42. Number of wild species |

Similar to the average for the region |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

43. Extent of compliance with animal welfare norm |

Standards for animal breeding |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < РС |

< < < RV |

44. Extent of preservation of ecosystem services |

Acceptance from communities |

>RV |

= RV |

< RV |

< < RV |

< < < RV |

Table 2 Levels of sustainability depending on the extent of achievement of the Reference Values for the sustainability indicator

Suggested approach will be helpful to determine and analyze the sustainability level for each indicator as well as to undertake measures for the improvement of sustainability for areas (indicators) with inferior values. For instance, all indicators for the sustainability in a particular farm may be good, but for the compliance with the animal welfare norms. Thus efforts to introduce and enforce the animal welfare standards in the farm would enhance the ecological and the overall sustainability of that holding. In order to present in a graphic form, diverse aspects and dimensions of the sustainability of a particular farm, and integrate different type of indicators for a particular criterion, principle and aspect of sustainability for one or a group of farms, the qualitative levels of each indicator are transformed into unit less Index of Sustainability (Isis) using Table 3.

Levels of sustainability |

Index of Sustainability (ISi) |

High |

1 |

Good |

0.75 |

Low |

0.50 |

Unsatisfactory |

0.25 |

Nonsustainable |

0 |

Table 3 Scale for transformation of qualitative levels into Index of Sustainability for a particular indicator

Figure 3 presents a result of the assessment on the level of sustainability of a case study farm in Bulgaria with a mix crop-livestock activity (Figure 3). It is apparent that in order to increase the overall sustainability of the holding it is to improve significantly the environmental protection activities of the farm. The later implies both a change in the strategy of the farm as well as targeted support policy of the state for stimulation of the eco-activity (function) of the farm. Very often individual indicators for each criterion and/or different criteria, principles and aspects of sustainability are with unequal, and frequently with controversial levels. That significantly complicates the overall assessment and requires an integration of the indicators.

The Integral Index for a particular criterion (ISc), principle (ISp), aspect of sustainability (ISа) or overall level for the farm (ISо) is an arithmetic average of indices of relevant indicators:

Integral Index 1 or close to 1 means a high sustainability, Index around 0.75 means good sustainability, while Index 0 or close to 0 a state of non sustainability. For interpretation of the integral assessments the Table 4 could be used.

Integral Index of Sustainability (ISIp,а,о) |

Sustainability level |

0.86 - 1 |

High |

0.63 – 0.85 |

Good |

0.36 – 0.62 |

Low |

0.13 – 0.37 |

Unsatisfactory |

0 – 0.12 |

Non sustainable |

Table 4 Limits for grouping of integral assessments of sustainability of farms

Figure 4 represents the integral assessment of a case study farm for all aspects of the sustainability. It is apparent that the evaluated farm is with a good overall sustainability, which is determined by the high social sustainability and the good economic and managerial sustainability. At the same time the evaluated holding is with a low integral ecological sustainability, which requires taking measures for improvement of eco-performance.

It is well known that every integration of indicators of different type is associated with much provisionality, as it implies an “equal importance” and certain “interchangeability” of the individual dimensions of sustainability. In particular, it presumes, that a low level of sustainability or a state of non-sustainability for one (several) indicator(s) could be “compensated” with a higher value of another (other) indicator(s) without a change in the integral level of sustainability. However, the later not always is true for the majority of indicators for the managerial and economic sustainability in a short-term, as well as in a longer-term for many of the indicators for social and ecological sustainability. For instance, a lack of governance or economic sustainability rapidly makes the entire farm unsustainable (transformation, failure).

According to the panel of experts, it is not necessary to give a different weight for the individual indicators when calculating the Integral Index for particular criteria, principle, aspect or the overall level of sustainability. However, when the level of sustainability for any of the indicators is unsatisfactory or zero, it is to be analyzed its importance for the evaluated farm(s). Furthermore, in longer periods of analysis the lowest level of sustainability for any indicators (criterion) will also determine the integral level for the particular aspect and the overall level of the sustainability of the farm.19

The overall and particular (aspect, principle, criterion, indicator) sustainability of the farms of a specific type, kind, and location is an arithmetic average of these of the individual farms.

The integration of indicators does not diminish the analytical power since it makes it possible to compare sustainability of the diverse aspects of the individual farm as well as of farms of different type and the entire sector. Besides, since the assessment of the sustainability levels for the individual indicators is a (pre)condition for the integration itself, the primary information always is available and could be analyzed in details if that is necessary.

Depending on the final users and the objectives of the analysis the extent of the integration of indicators is to be differentiated. While farm managers, investors, researchers etc. prefer detailed information for each indicator, for decision-making at the highest level are needed more aggregated data for the farms as a whole, major aspects of sustainability etc.

Investigating the farm as a governance structure becomes a key for understanding the farm sustainability. Accordingly, the concept of farm sustainability emphasizes to incorporate one new important dimension the “governance efficiency and adaptability” and its assessment include a new criteria and appropriate indicators for measurement and analysis. The later would require a new type of microeconomic data on agent’s preferences, transaction costs, institutional environment, etc.

It has been suggested in this paper , that system for assessment of the sustainability of farms will be tested over period of time and the level of sustainability of farms in one of the regions of Bulgaria will be defined by revealing the improvements of the new system . Subsequently, the tested system of assessing farms sustainability will then be suggested for a wider use in the farm and managerial practices.

None.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

©2016 Bachev. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.