Advances in

eISSN: 2373-6402

Review Article Volume 8 Issue 6

Department of Biology and Environment, University of Tras-osMontes and Alto Douro, Portugal

Correspondence: T Pinto, University of Tras-os-Montes and to Douro, Biology and Environment Department, Centre for the Research and Technology of Agro-Environmental and Biological Sciences (CITAB), 5001 801 Vila Real, Portugal,

Received: July 04, 2018 | Published: November 17, 2018

Citation: Pinto T, Vilela A. Kiwifruit, a botany, chemical and sensory approach a review. Adv Plants Agric Res. 2018;8(6):383-390. DOI: 10.15406/apar.2018.08.00355

The kiwi is a fruit with a great agricultural, botanical, and economic interest. Originally from China, this species is currently widespread in practically all the world, due to the high nutritional value of the fruits, excellent organoleptic qualities besides therapeutic benefits in the health. The most common kiwifruit species grown commercially is Actinidia deliciosa even though many varieties of this fruit are produced by other cultivars or by another kind of plants, such as Actinidia chinensis and the Actinidia kolomikta or the Actinidia argute. Although there are many varieties in this species, the A. deliciosa Hayward cultivar is the most popular variety marketed commercially. Kiwifruits contain aromatic compounds able to attract consumers due to their palatability. The esters, ethyl butanoate and methyl benzoate and the aldehyde E-2-hexenal, were shown to increase “characteristic kiwifruit aroma and flavor”. All these characteristics are appreciated by the kiwi-consumers. Several preservation techniques have now been used to augment kiwi shelf life, including cold storage, chemical dipping, modified atmosphere packaging and edible coatings, making it possible for the consumers to enjoin the fruit all the year.

Keywords: kiwifruit, Actinidia, kiwi cultivars, bioactive compounds; sensory characteristics

Kiwi - history, producer countries and health benefits

Kiwifruit is botanically known as Actinidia deliciosa.1 This species was first found along the border of the Yangtse River valley in China and later, in 1847 and 1904, the first plants were send for England and America, respectively.2 According to official records, the first commercial plantings were established in New Zealand in 1937. The expansion of this species throughout the world began to take place in the 1960s with the export of New Zealand plants and seeds to destinations such as Germany, Italy, Spain, India, South America, Morocco, Israel and South Africa.2 By the 1980’s, other countries around the world began to produce and export kiwi. At present, commercial growth of the fruit has spread too many countries including the United States, Italy, Chile, France, Greece, India and Japan. Figure 1 shows the top kiwifruit producing countries in the world.3

Indeed, this fruit is widespread throughout the world, due to his high nutritional value, with high levels of vitamin C, besides the excellent organoleptic qualities, associated with its adaptability to temperate and subtropical climates. Several studies4‒8 showed that kiwifruit packs more nutrients than other commonly consumed fruit (Figure 2), and highlight its therapeutic benefits in healthy metabolism, iron content, digestive potential, antioxidant property, immune function and also his protective effects against coronary artery disease. As a source of ascorbic acid and polyphenols, the kiwifruit aids in lowering the risk of arteriosclerosis, cardiovascular diseases, and some forms of cancer,9 in irritable bowel syndrome,10 and also protect the cells in-vitro from oxidative DNA damage.11

The genus Actinidia belongs to the family Actinidiaceae, to the order Ericales, to the class Magnoliopsida and to the division Magnoliophyta. There are dozens of species comprising the genus Actinidia.12 The most common kiwifruit species grown commercially is Actinidiadeliciosa (green kiwi), even though many varieties of this fruit are produced by other cultivars or by another kind of plants, such as Actinidia chinensis (yellow kiwi) and the Actinidia Kolomikta or the Actinidia arguta (baby kiwi).13 In fact, the world production of A. arguta already corresponds to 17% of the total kiwi produced worldwide, with A. deliciosa and A. chinensis being the most produced species, with 37% and 31%, respectively, and A. kolomitka and other inter specific hybrids the species with the lowest world production, with 8% and 7%, respectively.14 Below are described the most important varieties of kiwis, the point of view of their production and consumption of each type or species. Each variety of kiwifruits has particular characteristics, due to the ability to adapt to the soil and to the local climate conditions.

Actinidia deliciosa cultivars (green kiwi)

Actinidia deliciosa is the most widely cultivated species in the world. As its name suggests, it has a bright green pulp and an acidic taste, which usually has 12 to 14º Brix at the time of consumption. It has exceptional nutritional properties, with very high mineral and vitamin contents, being one of the fruits with the highest content in vitamin C. Although there are many varieties in this species (Table 1), the A. deliciosa Hayward cultivar is the most popular variety marketed commercially.13

Hayward (female) variety

This variety presents medium vigorous plant and is very productive. The flowers are usually solitary, one per peduncle, large, 5 to 7cm in diameter and very attractive, with white petals (Figure 3). The fruit is large, with an average weight greater than 100g, ellipsoidal shape, and has a high density, which makes it one of the best in the volume-weight ratio of all the cultivated Actinidia species. The skin is brown, with a background more or less green, and is coated with a thin and thin hair (Figure 3).

The pulp is very juicy at maturity and with very good flavor, bright green, turning yellowish in the maturity of consumption. It also well adapted to conservation by refrigeration, up to more than six months in an atmosphere controlled. In the last years some clones have appeared derived from Hayward, with better characteristics of the fruit.13,15,16

Other varieties of traditional green kiwi are present in Table 1. According to Garcia et al.,13 Allison, Elmwood, Green sil, Gracie, Vicent, Blake, etc. are cultivars similar to these, but all of them have no commercial interest because of the smaller caliber of the fruit, lower productivity and fundamentally because of a much shorter cold storage.13

Male (A. deliciosa)

Most male cultivars have been selected to coincide in flowering with Hayward, the predominant fruiting cultivar. Effective pollination, seed set, and full-sized fruit require coincident flowering of males and females but weather conditions during spring have a major effect on the time of flowering of males, relative to that of Hayward. Different males are therefore being selected for the different growing countries. So, there are many cultivars of males available. Examples include Matua, Tomuris, Cal Chico Nº3, Chico Early, and Chico Extra Early.17

Actinidia chinensis cultivars (yellow kiwi)

The fruits of this species cultivars (Table 1) are characterized by having a bright yellow flesh, lower acidity and a greater sweetness than the green kiwi, what which makes them more desirable in the Asian market.13 In the present, the Hort16A (Zespri® Gold) is the cultivar of this species most cultivated in the world.13

Hort16A (Zespri® Gold) variety

Obtained in New Zealand in 1992, and marketed under the commercial name ZESPRITM GOLD Kiwifruit -ZESPRITM is the name of the marketing subsidiary of Kiwifruit New Zealand, the successor to the New Zealand Kiwifruit Marketing Board.18 The fruit is of average size and very characteristic for having a very pronounced floral end (Figure 4). It has yellow pulp and high in sugar, vitamin C, E and iron, with a tropical fruit flavor. Very productive and harvest season similar to Hayward.13

Actinidia arguta and Actinidia kolomikta cultivars (baby kiwi)

Two other Actinidia species have a fruit of obvious commercial potential: these are A. arguta and A. kolomikta.19 The fruits of these species are known globally as "baby kiwi", "mini kiwi "or" kiwi berry13 because the fruit is about the size of a European gooseberry or grape, rarely exceed 25g. The skin is smooth and polished, completely hairless, without any villus and edible, colored green and with reddish tones in some varieties. The pulp is green bright, with the flavor similar to green kiwi, but sweeter. They have a greater content in antioxidants that the rest of the kiwis, and a higher vitamin content and minerals. The conservation period is short conservation, about 2 or 3months".13s The cultivars of this two species are presented in Table 1.

Figure 4 A. chinensis Hort16A kiwi fruit.18

Species |

Cultivars |

References |

|

Hayward CLON 8 |

Is a clone derived from Hayward, very productive, which has an average weight 20% higher than this and matures a week before? It produces a lower percentage of double fruits and is more resistant to frost. It is also less susceptible to Phytophthora that Hayward |

||

Top Star |

Is a mutation of Hayward' very productive, with good size fruit and lacks hairiness. It is vigorous and has a very compact vegetation |

||

Summer Kiwi |

It is very productive and it can be something more vigorous than Hayward. It has little tendency to emit flowers triples per peduncle. The fruit is something smaller than Hayward, with a weight medium of 85g; has less acidity and more sweetness than most varieties of green kiwi. The conservation refrigeration is less than Hayward |

||

Bruno |

It is distinguished from other varieties by its luxuriance vegetation and intense green of its foliage. It has the flowers slightly smaller than Hayward. The fruit is of medium size, from 60 to 70g and completely cylindrical. The skin is dark brown, with a lot of hairiness, long and hard hairs. The pulp is translucent green, acidulated and contains more vitamin C than most of the varieties. Cold storage it is inferior to Hayward. |

||

Abbott |

It is a vigorous cultivar and of entry into early production. It blooms 3 or 4days before the 'Hayward' and its harvest is a week before. The fruits are of light brown color and abundant pilosity, with the central column of the pulp much harder than the other cultivars |

||

Monty |

It has cold winter needs lower than 'Hayward' (500h) and more tolerant to drought than other cultivars. Flowering and harvesting times are similar to 'Abbott' and 'Bruno', and their conservation is shorter than Hayward. Its fruit weighs are between 80 and 90g, with characteristic vertical striations and with a tendency to produce 3 fruits per peduncle. Although slightly acidic, its fruit is tasty. |

||

Saanichton 12 |

The fruits are large, weighing between 70 and 80g, somewhat more rectangular than Hayward, sweet, and of good flavor. It seems hardier than Hayward |

||

Jing Gold |

The fruit is smaller in size than Hort16A, it has yellow pulp and sweet taste. Is very productive and it is harvested approximately when Hayward. It seems that It is less sensitive than other varieties yellow, to Verticillium and Bacteriosis. It can keep up to 6 months. |

||

A. chinensis |

A19 (Enza Gold) |

Fruit with external characteristics very similar to Hayward, with yellow pulp and greater acidity than the previous ones. Very productive. |

|

JB Gold (Kiwi Kiss) |

Is highly productive, being able to surpass 50 t/ha. The fruit is one of that larger size, within the varieties of yellow fruit. The date of collection is similar to Jintao and Hayward. |

||

Sungold |

Brother of 'Zespri® Gold', with a bright yellow flesh and a flavor very tropical. It is devoid of hairiness and it differs from his brother in that the floral end is not as pronounced. |

||

Sorel |

Has very short internodes and good fertility of floral buds, what makes it very productive sprouting. It tolerates better the cold than the other varieties yellow, due to its a little later The fruit is of good size (average of 100g), with yellow pulp and clear brown skin, without hairiness. |

||

Ananasnaja |

It is a cultivar very productive The fruits are almost always grouped in clusters of three units, are green with shades reddish in the sunniest part and small size, 3-5g. The pulp is very sweet and aromatic, remembering the pineapple. |

||

Meader |

It is a self-fertile variety, although for commercial production improves your productivity with a pollinator. the fruits are light green, with pulp green bright and very sweet |

||

Larger |

It is a variety native to mountainous areas, acclimated to very adverse conditions, both of drought in summer, as of cold and wind in winter. The fruit is very sweet. It has a tendency to produce a single fruit per peduncle. |

||

A. arguta |

Santyabraskaya (A. kolomikta) |

It is a variety with foliage very attractive in autumn for its discoloration. The fruit is yellow-greenish, of small size 3-4g. |

|

Szymanowski |

It is a variety that behaves as self-fertile. Has very original foliage, with part of the white and green leaves, acquiring some pink tones during the summer. The fruit is yellowish-green and with a certain flush in the sunniest part, have an oval shape and an average weight of 3-4g. |

||

Jumbo(A. arguta) |

The fruits are large, the largest of the species, with an oblong shape and yellowish green color. It is late flowering. It needs a male pollinator. |

||

Issai(A. arguta) |

It is self-fertile, although in production commercial is important the help of a pollinator to increase production. The fruit is cylindrical, with an average fruit weight of 6-8g. |

||

|

Transcarpathia |

It is a new self-fertile variety. The fruit is green, cylindrical and with an average weight of 70-80g, the largest of these species. |

|

Table 1 Kiwi cultivars

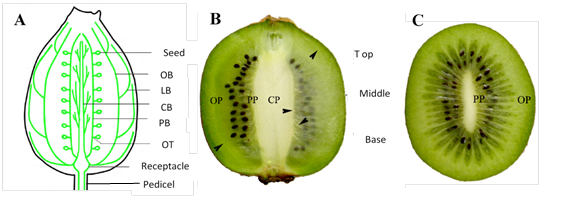

Each species and cultivar of kiwifruits has particular characteristics, due to the ability to adapt to the soil and to the local climate conditions. So, kiwis are fruits of trees, climbing shrubs, or woody vines, that could be reaching nine meters.20 The plant is characterized by fleshy roots, very branched and with a tendency to distribute in the upper substrate of the soil. It has flexible stems: are woody at the bottom and tender and twinning at the top, whose tendrils are used to hook on the support (Figure 5C).17,21 The kiwifruit leaves are deciduous, alternate, simple, shortly or long petiolate not stipulate, oval to nearly circular, cordate at the base, with the length between 7.5 and 12.5cm, and width between 15 and 20cm (Figure 5A). Young leaves are coated with red hairs; mature leaves are dark-green and hairless on the upper surface, downy-white with prominent, light-colored veins beneath.20,21 Kiwi is a dioecious or bisexual plant, male and female flowers appear on different plants and both sexes have to be planted in close proximity to fruit set. The kiwifruit flowers are fragrant, borne singly or in 3's in the leaf axils. They are 5- to 6-petaled, white at first, changing to buff-yellow, 2.5 to 5 centimeters broad, and both sexes have central tufts of many stamens, though those of the female flowers lack viable pollen.20 The flowers also lack nectar (Figure 5B). Kiwi fruits derived from compound pistil ovary, and its vascular bundles are mainly distributed in three distinct regions: CP, PP, and OP. The axile placenta of fruit is mainly formed of homogeneous and very large parenchymatous cells (Figure 6A–6C). The fruit is a berry, gathered in clusters of ovoid shape, spherical or elongated, depending on the cultivar. It has on the outside, hair of a brownish-green color, usually soft. Its flesh is green and small black seeds are arranged in a circle about the center.20,21 According to the varieties, the average weight, shape, and color of the kiwifruit may vary (Figure 7).

Figure 5 Comparing the common "fuzzy" kiwi (A. deliciosa) with the Hardy Kiwi (Actinidia arguta). The Hardy Kiwi has soft, smooth, edible skin.19

Figure 7 Kiwifruit, A - Longitudinal mid-section, showing the arrangement of the major vascular bundles in fruit: CB, central placenta vascular bundle; LB, lateral branch bundle; PB, placental vascular bundle; OB, ovary wall vascular bundle; OT, ovule trace; SB, septum vascular bundle. B - Longitudinal mid-cross section of fruit, showing many carpel’s around the axile placenta. C-Transversal mid-section of fruit: CP, central placenta; PP, peripheral placenta; OP, outer pericarp.22

Fruit quality depends on its preharvest development, such as changes in color, flavor, and texture as fruits develop, grow, and ripen, as well as its maintenance following harvest as theperishable tissues senesce.23 All plants are able to emit volatile organic compounds and the content and composition of these molecules depens on genotic and phenotypic traits.24 Is well known that volatile flavor compounds are likely to play a key role in determining the perception and acceptability of products by consumers. Identification of key volatile flavor metabolites that carry the unique character of the natural fruit is essential, as it provides the principal sensory identity and characteristic flavor of the fruit. Bound volatiles are recognized as a potential source of aroma compounds in kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa).25 Moreover, the flavor of kiwifruit namely Actinidia deliciosa seems to be a blend of several volatile components belonging to the family of esters, alcohols and aldehydes.26 The fruit during ripeningproduces a large number of volatile compounds that have been studied by several authors.27,28 The main components identified in these reports works are methyl and ethyl butanoate (with fruity, fresh, berry, grape, pineapple, mango and cherry notes), hexanal, (Z)- and (E)-2-hexenal (fresh green, leafy, fruity with rich vegetative nuances), hexanol, (Z)-, and (E)-3-hexenol (green, fruity, apple skin, oily) and methyl benzoate (phenolic and cherry pit with a camphoraceous nuance), all of which are typical degradation products of unsaturated fatty acids.29 Friel et al.,30 and Gunther et al.,31 refer that the volatile profile of eating-ripe “Hort16A” kiwi is dominated by ethyl esters and the aromatic compound 3-(methylsulfanyl) ethyl propionate has been suggested to contribute to the “tropical aroma” of non-stored kiwifruit. Although “Hort16A” has been less studied than “Hayward”, it has been mentioned that an important difference between the aroma profiles of “Hort16A” and “Hayward” is the presence of diverse Sulphur compounds in the last.25

Color and appearance attract the consumer to a product and can help in impulse purchase once, at the point of purchase the consumer uses appearance factors to provide an indication of freshness and flavor quality. External appearance of a whole fruit is used as an indicator of ripeness. Consumers have a preferred color for a specific item.32 Bananas “must” be yellow with no brown spots, tomatoes red, cherries red not yellow, and kiwifruit green-fleshed.33 The kiwifruit presents a high nutritional value, rich mainly in vitamin C and fibers, calcium, iron and phosphorus, which turns it into an excellent nutritional option, with an important association between quality attributes and flavor, with great acceptance in consuming markets.34 The flavor of kiwifruit is affected by maturity at harvest and storage conditions. Paterson et al.,35 found that these conditions also affected the fruits chemical composition and that there were correlations between the levels of compounds and the sensory properties. The esters, ethyl butanoate and methyl benzoate, were shown to increase sweet aroma and flavor.36 Ethyl butanoate and hexanal were shown to increase sweet aroma37 and E-2-hexenal increased “characteristic kiwifruit aroma and flavor”.26 All these characteristics are appreciated by the kiwi-consumers. In a work by Gilbert et al.,38 the New Zealand consumer-guidance panel was used to explore perception and acceptability of selected volatile flavor compounds, namely ethyl butanoate, E-2-hexenal and hexanal, in relation to kiwifruit flavor. A juice model was chosen to study these relationships and a factorial experimental design was utilized to measure possible interactions between and among compounds. The authors found that Ethyl butanoate and E-2-hexenal had the greatest effects on consumer perception and acceptability of kiwifruit flavor. Ethyl butanoate alone, positively affected “overall liking,” “liking of aroma” and “liking of flavor.” A negative effect was found for E-2-hexenal on “overall liking,” “liking of aroma” and “liking of flavor.” In the absence of ethyl butanoate increasing levels of E-2-hexenal and hexanal increased the perceived intensity of “kiwifruit aroma.” “Ideal” intensity of “kiwifruit aroma” and “kiwifruit flavor” may require the presence of all three volatile flavor compounds.

Kiwifruits are mostly eaten as fresh, although some kiwifruits are also processed into juices, drinks, purees, candies, frozen, dehydrated and lyophilized products.39 The green kiwifruit (A. deliciosa) is not usually processed due to the fact that the chlorophyll responsible for the attractive green-color gets destroyed during processing40 and its characteristic flavor of green kiwifruit gets lost. The golden kiwifruit (A. chinensis) is well adapted to food processing once the yellow color of the fruit survives well in processed products like juices and jams. For the fruits that do not meet quality standards of the fresh fruit market, processing can be an alternative for adding value to the product. Several kiwi-preservation techniques including cold storage, chemical dipping, modified atmosphere and edible coatings have been used to prolong the shelf-life and retain the nutritional value of fresh-cut kiwi fruits. Small quantities of fruit that do not meet grade standards are used for cosmetics or nutraceuticals. Minimally processed fruit and vegetables cannot be heat treated so, one of the alternatives is to store them at refrigeration temperatures (<5°C) in order to ensure a long shelf-life and microbiological safety.41 Refrigeration at 2°C and a RH of 90%, associated with calcium chloride or calcium lactate treatment can prolong the shelf life of minimally processed kiwifruit slices up to 9-12days.42 MAP (Modified Atmosphere Packaging) in combination with alginate-based coatings delayed dehydration, microbial spoilage and respiratory activity in fresh-cut kiwifruit.43 But, this technique must be used in combination with other preservation techniques in order to achieve a sufficient shelf life.

Edible coatings

Edible coatings act as a semi-permeable barrier to respiratory gases and water vapors between the fruit and the atmosphere. These also act as barriers to microbial agents.44 Alginate, a natural polysaccharide extracted from brown sea algae (Phaeophyceae) comprising of two uronic acids: β-D-mannuronic acid and α-L-guluronic acid, have been used as coating in whole and fresh-cut fruits namely in peeled kiwifruit slices.43 Chitosan (a linear polysaccharide composed of randomly distributed β-(1→4)-linked D-glucosamine (deacetylated unit) and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (acetylated unit), made by treating the chitin shells of shrimp and other crustaceans with an alkaline substance, like sodium hydroxide)coating applied to red kiwifruit (Actinidia melanandra) has been found to maintain higher amounts of phenolics and ascorbic acid slowing down the decomposition rates.45 In the field of edible coatings, a recent development has been the use of aloe vera gel. Aloe vera coating has been found to reduce microbial proliferation and to maintain the fruit firmness, preventing ascorbic acid losses and yellowing due to ripening in fresh-cut kiwifruit.46 Another new material used is the mucilage from Opuntia-ficus-indica (a species of cactus that has long been a domesticated crop plant important in agricultural economies throughout arid and semiarid parts of the world). Kiwifruit slices coated with opuntia ficus-indica have been reported to maintain firmness, ascorbic acid and pectin content.47

Originally from the orient, kiwi is currently widespread around the world and due to the high nutritional value of the fruits therapeutic benefits in the health and excellent taste and flavor, is a fruit chose by consumers. Actinidia deliciosa Hayward cultivar is the most popular variety marketed. Besides, is a fruit that can be adapted to several utilizations and cooking recipes? It can be consumed fresh or processed into juices, drinks, and purees, candies, frozen, dehydrated and lyophilized. It can be used in dessert and in main courses. For those who want to have this fruit all year, several preservation techniques can be used to enhance kiwi shelf life, including modified atmosphere packaging and edible coatings.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 Pinto, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.