Advances in

eISSN: 2373-6402

Recent evidence suggests that winter-red leaf phenotypes in the mastic tree (Pistacia lentiscus L.) are more vulnerable to chronic photoinhibition during the cold season, relative to winter-green phenotypes occurring in the same high light environment. The present study deals with the previously recorded induction of anthocyanins in leaves of winter populations of mastic tree, examining their correlation with cellular status and the potential coordinated involvement of reactive species networks. Red leaves with increased amounts of anthocyanins show higher concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and nitric oxide (NO). Furthermore, red leaves show higher extent of cellular damage manifested by increased lipid peroxidation and lower photosynthetic pigment content compared with green leaves. The observed accumulation of reactive species is supported by increased activity of H2O2 (superoxide dismutase) and NO-producing (nitrate reductase) enzymes, respectively. Winter leaf redness may therefore be potentially used as a rapid phenotyping means to locate vulnerable mastic tree plants suffering from nitro-oxidative stress.

Keywords: pistacia lentiscus l, anthocyanins, nitric oxide, hydrogen peroxide, winter leaf reddening, antioxidants

NO, nitric oxide; RONS, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species; SOD, superoxide dismutase; NR, nitrate reductase; MDA, malondialdehyde; TBA, thiobarbituric acid; CAT, catalase

Leaves of many angiosperm evergreen species change color from green to red during winter, corresponding with the synthesis of anthocyanin pigments. The ecophysiological function of winter color change (if any) is not yet fully understood. Nevertheless, the transient red leaf character has been preserved and several compensating functions have been suggested.1 It has been proposed that the accumulation of red anthocyanins may provide photo protection either as a passive light screen or as a potent antioxidant.2 Nevertheless, contradictory reports also exist which did not show such protective, antioxidant function in leaves high in anthocyanins.3

Previous investigations with the species Pistacia lentiscus L. show that the strength of leaf redness (characterized by marked increase in anthocyanin levels) is positively correlated to the extent of mid-winter chronic photoinhibition and suggest that leaf redness may be used reliably, quickly and non-invasively to locate vulnerable individuals in the field.4 Furthermore, during the cold (“red”) season, net CO2 assimilation rates, stomatal conductances and leaf nitrogen levels in the red phenotype were considerably lower than the green phenotype, while leaf internal CO2 concentration was higher.5 This suggests a probability that the inherently low leaf nitrogen levels are linked to the low net photosynthetic rates of the red plants through a decrease in Rubisco content. Accordingly, the screening effect of the accumulated anthocyanins cannot be fully alleviated.

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) such as H2O2 and NO, respectively, constitute key features underpinning the dynamic nature of cell signaling systems in plants. They are involved in many key physiological processes, including plant growth and development, stomatal movement and in response to adverse environmental conditions.6 Recent evidence suggests that a strong cross-talk exists between oxidative and nitrosative signaling upon abiotic stress conditions.7 Plants in field conditions experience various stresses leading to the overproduction of RONS which are highly toxic and can cause damage to proteins, lipids, carbohydrates and DNA and ultimately result in oxidative stress.8 Reactive species are generated mainly enzymatically; examples include the dismutation of superoxide radicals to H2O2 with the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD),8 while NO is mainly generated in plants by the reduction of nitrate via nitrite to NO, catalyzed by nitrate reductase (NR).9

The present study attempts to examine the potential coordinated involvement of RONS networks in winter leaf reddening in Pistacia lentiscus L. by estimating cellular integrity parameters and H2O2/NO content, further supported by biochemical activity assays of major RONS biosynthetic enzymes, thus providing novel insights into the link between high leaf anthocyanin content and the complex regulation of NO and H2O2 metabolism in red leaf phenotypes of mastic tree individuals.

Plant material and growth conditions

A natural population of P. lentiscus L. shrubs was used, located within the Patras University campus (38°18′N 21°47′E) and containing both winter-red and green phenotypes side-by-side under similar full sunlight exposure. Phenological observations for leaf color indicated that redness appeared roughly at mid-January and lasted up to late April. Mature south-facing leaves of 1-1.5year old plants were sampled in the field during clear days (PAR at 1400-1600μmolm-2s-1) in late March. For all measurements, 3 leaves from 10 independent, tagged shrubs (5 red, 5 green) were harvested, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C for subsequent use.

Cellular damage indicators

Leaf pigments were extracted from 9mm-diameter leaf discs in dimethyl sulfoxide as described by Richardson et al.10 Carotenoid and chlorophyll concentrations were determined using the equations described by Sims et al.11

Anthocyanins=0.0821∗A534−0.00687∗A643−0.002423∗A661

Chlorophyll b=0.02255∗A643−0.00439∗A534−0.004488∗A661

Chlorophyll a=0.01261∗A661−0.001023∗A534−0.00022∗A643

Carotenoids=(A470−17.1∗(Chla+Chlb)−9.479∗anthocyanins)119.26

The extent of lipid peroxidation was determined from measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA) content resulting from the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) reaction as described by Hodges et al.,12 using an extinction coefficient of 155mM-1 cm-1.

Hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide quantification

Hydrogen peroxide was quantified using the KI method, as described by Velikova et al.13 Nitrite-derived NO content was measured using the Griess reagent in homogenates prepared with Na-acetate buffer (pH 3.6) as described by Zhou et al.14 NO content was calculated by comparison to a standard curve of NaNO2.

Enzyme activity assays

The nitrate reductase (NR) assay was performed as described by Liu et al.15 Cell extract was centrifuged at 14,000×g for 15min and the clear supernatant was used immediately for measurement of enzyme activity. NR activity was expressed as specific enzymatic activity (units/mg protein). For SOD and CAT extraction, leaf samples were homogenized in ice-cold extraction buffer (0.1M phosphate buffer pH7.5, 0.5mM EDTA, 1mM PMSF) using mortar and pestle. Each homogenate was centrifuged at 16,000×g at 4°C for 20min and total supernatant was used for enzymatic activity assay. Total superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was determined as described by Giannopolitis et al.16 One unit of SOD activity (U) was defined as the amount of enzyme required to cause 50% inhibition of the NBT photoreduction rate. The results were expressed as specific activity units/mg protein. Catalase (CAT) activity was measured according to Aebi.17 The rate of H2O2 disappearance was monitored at 240nm during 3min. Total protein content of all samples was determined by the Bradford method.18

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v.11 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Biochemical and cellular damage measurements were subjected to ANOVA, and then significant differences between individual means determined using Tukey’s pair wise comparison test at the 5% confidence level.

The adaptive significance of leaf reddening, during plant development or under stress conditions, has been for biologists. In theory, the accumulation of a non-photosynthetic pigment competing with chlorophylls for photon capture would impose a photosynthetic cost, which should be paid off by the benefits awarded by anthocyanins under specific circumstances. This maintains that, whenever the balance between light absorption and further processing of redox energy is perturbed and the usual means of over excitation avoidance (or tolerance) are surpassed, the accumulation of anthocyanins may function as a passive light screen and/or towards ROS detoxification.1 The inherent need of the plant to balance the energy absorbed from the sun with the photosynthetic yield and productivity is considered to be quite significant during the cold period of the year in evergreen species of the Mediterranean region. This need exists mainly due to cold temperatures in combination to high light conditions.19

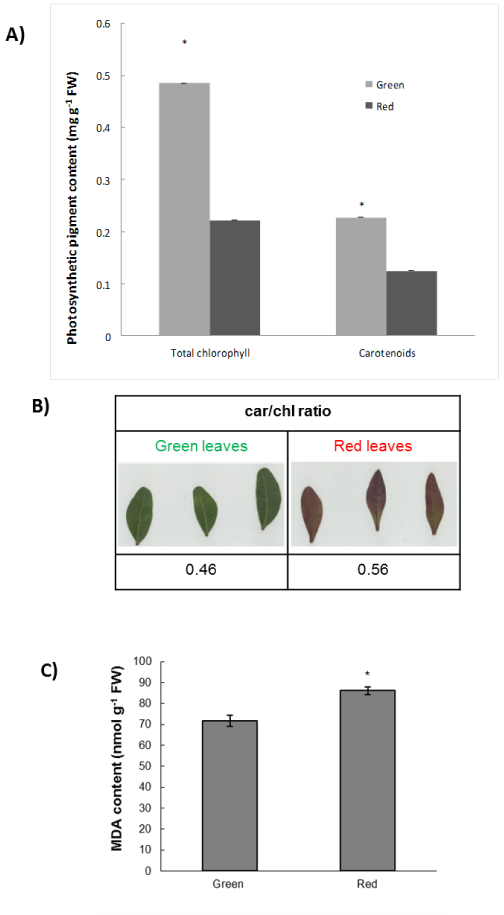

The present study provides novel evidence regarding the interplay between the biosynthesis of H2O2 and NO in relation with the associated cellular damage observed, as well as the previously recorded (see4) induction of anthocyanins in mature leaves of winter mastic tree individuals. The results collected from our previous investigations showed that the vulnerability of the red phenotype compared with the green phenotype can be measured through a series of physiological parameters such as net CO2 assimilation rates and stomatal conductances.4,5 Present findings provide further supporting evidence of previous reports, as the vulnerability of the red leaves was substantiated by the observed increase in cellular damage manifested through increased MDA content (Figure 1) and the significant induction of H2O2 and NO biosynthesis indicative of oxidative and nitrosative stress, respectively.

Biochemical analyses suggest that the lower concentration of total chlorophylls in the red phenotype (Figure 1A) may potentially indicate an adaptation against the excess light absorption.20 Furthermore, the lower content in carotenoids in red leaves (Figure 1B) could explain the higher degree of oxidative stress which the red phenotype suffers from. However, the car/chl ratio in red leaves is higher than in green leaves (Figure1C); given the antioxidant role of carotenoids, this induction could represent an attempt by the plant to cope with increased levels of oxidative damage. It is widely recognized that phenolic compounds are involved in the ROS scavenging cascade in plant cells.21 It is therefore possible that high ROS content in the red phenotype could be a result of a potentially lower concentration of phenolics, although biochemical evidence provides support for the observed H2O2 accumulation (Figure 2A) via the increased enzymatic activity of SOD (which dismutates superoxide radicals to H2O2) in the red phenotype (Figure 2B), further linked with increased CAT (H2O2 catabolic) activity (Figure 2C). Interestingly, the increased presence of anthocyanins seems not to be able to diminish the ROS-derived oxidative damage. However, it should be noted that the concentration of anthocyanins only represents a small fraction (ca. 1–1.5%) of the total phenolic pool,22 while the contribution of anthocyanins to the total leaf light and UV-B absorbing capacity–which is one of the main causes of production of ROS content, especially under field conditions–is negligible.23

In regard with RNS signaling, red phenotype plants appear to be under nitrosative stress as evidenced by the increased NO content (Figure 2D). The increase in NO content is compatible with the increase in NR activity (Figure 2E), in agreement with previous reports.7,24 This is expected as NR is the key biosynthetic enzyme for NO generation.9 Previous findings by Antoniou et al.,24 showed that NO accumulation in senescing Medicago truncatula plants exhibiting advanced chlorophyll degradation may exert a repressive effect on nitrate influx, manifested by the suppressed expression of a putative nitrate transporter gene. These plants demonstrated increased sensitivity to nitrosative stress possibly due to a negative feedback regulation of this nitrate transporter via products of NO3- assimilation (i.e. NO). A similar regulation of nitrate influx and overall limited ability to absorb nitrogen could potentially explain, at least partly, the low levels of nitrogen found in the red phenotype in relation to the green phenotype,5 which are in turn associated with low Rubisco content level through the involvement of nitrogen in the enzyme’s chemical structure,5 thus providing a clear link with the observed diminished photosynthetic capacity and lower chlorophyll levels.

Interestingly, stomatal closure is controlled by a number of hormones (including ABA and brassino steroids), while the importance of NO and H2O2 signaling and regulation in stomatal movement is also well documented.25,26 Recent evidence indicates that winter-red leaf phenotypes in the mastic tree show lower stomatal conductance than the green phenotypes in winter.5 Present findings suggest that the high levels of H2O2 and NO in red phenotype during winter may contribute to stomatal closure, resulting in lower level of stomatal conductance. Of particular interest would be to cross-examine the vulnerability of the red leaf individuals to other abiotic stress factors in field conditions, as the observed induction in antioxidant enzyme (SOD, CAT) activity is normally linked with tolerant tree species such as with the case of Ailanthus altissima.7

To our knowledge, this is the first report evaluating the potential coordinated involvement of H2O2 and NO biosynthesis networks in winter leaf reddening in P. lentiscus. Our findings suggest that the increased anthocyanin content does not correlate with an up regulated antioxidant capacity but is instead associated with increased cellular damage levels, further arguing that winter leaf redness may be used to locate plants suffering from oxidative and nitrosative stress, proposing that these plants may have vulnerability at a genetic level. Further research at a molecular level could provide valuable new findings towards a more complete cellular and physiological characterization of these two distinct phenotypes, particularly under adverse environmental conditions.

This work was supported by Cyprus University of Technology Internal Grant EX032 to VF.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.