MOJ

eISSN: 2576-4519

Research Article Volume 2 Issue 2

1PhD Professor at the Health and Sports Science Center-CEFID/UDESC, Brazil

2Professor Master of the Southern University of Santa Catarina-UNISUL, Brazil

3Formado (a) in Physical Education at the University of Southern Santa Catarina?UNISUL, Brazil

Correspondence: Ana Claudia Vieira Martins, Professor at the Health and Sports Science Center-CEFID/UDESC, Rua coronel americo, 804-Barreiros/Sao jose, Zip code 88117-310, Brazil

Received: April 17, 2018 | Published: April 24, 2018

Citation: Martins ACV, Piemontez GR, Espíndola AM. Cinematic characteristics of technique gyaku-zuki no jion kata do karatê style shotokan. MOJ App Bio Biomech. 2018;2(2):164–168. DOI: 10.15406/mojabb.2018.02.00060

The study examined kinematic characteristics of the technique gyaku-zuki the first sequence of the kata jion karate Shotokan style. Participated kataístas 10, female, purple belt, brown and black, with participation in at least one state competition. A simulation of kata competition in which the judges evaluated and rated the performance of the athletes was held. We used a registration form, and kinematics system with Xsens MVN inertial central Studio. Variables of the technical profile of athletes (undergraduate, workout time, frequency of weekly training, level of competitions which he participated, and position in the state ranking) and kinematic variables: runtime, maximum linear speed and average linear acceleration. To characterize the technical profile of the athletes and the kinematic variables: descriptive statistics; for comparisons between the two groups according to performance in the execution of the first sequence of the kata jion (Group 1: 1st to 5th position, and Group 2: 6th to 10th position): Student t test. The confidence interval was of 95% (p<0.05). Results: a) the kata athletes have technical profile consistent with good result played by them in competitions; b) the athletes in Group 1 performed the technique gyaku-zuki in less time (0,375s), higher values of maximum speed (10,51m/s) and mean acceleration (4,94m/s2) compared to Group 2 (0.503 s, 5,75m/s, 2.38M/s2, respectively). There were significant differences in all kinematic variables. We conclude that the athletes in Group 1 had better performance in the execution of technical gyaku-zuki, can be attributed to technical profile of athletes.

Keywords: biomechanics, gyaku-zuki, martial arts, statistics

The gyaku-zuki is a technique of attack that consists of the execution of a punch with the hand opposite the leg that is the front in the base.1 In addition, it is an important element of the basic techniques of karate, practiced with great frequency in the lessons during kihon and widely emphasized in the training of techniques for the sport fight (shiai kumite), in front of the great speed of execution.2–4 This technique is also present in kata competitions composing the sequences of movements required by the Kata Reg Rules. The kata is the execution of a fight against several imaginary opponents that are based on the kihon (basic technical bases, defense, kicks and punches).5–11 For the proper execution of a kata, it is necessary to use the correct techniques, the ideal application of force, breath control and various coordinating abilities.12–14 The execution of the kata is evaluated according to the Rules of Karate Arbitration of the Brazilian Confederation of Karate Interestilos (CBKI)15 and by the Brazilian Confederation of Karate (CBK).5 Aspects regarding the immobility of the athlete in the execution of certain techniques as well as the speed of execution, are analyzed by the referees during the competition. In addition, rhythm, harmony, and time intervals between each movement or series of movements are also considered important. Taking into account the unique rules of kata, it is attributed to the qualitative evaluation of the referees on the performance of the athletes, notes that will represent, in a quantitative way, the result of each athlete at the end of the competition. This qualitative assessment of the referees can be attributed to the ability of human vision to be 24Hz, limiting the perception of movement details at high speeds. Specifically to the study of gyaku-zuki in kata, only one study was found that analyzed the angular velocity and joint amplitude of the elbow during the execution of this technique.1 The other studies on gyaku-zuki are directed to kumitê and kihon (fundamentals), which analyzed variables such as: linear velocity and wrist acceleration in athletes black bands in Kumitê,17–19 average linear velocity of the upper limb of karatecas black belt,20 and impact.21 For this, considering: a) this technique is the first one to be evaluated by the referees in jion kata competitions, b) the need for this technique to satisfactorily meet the evaluation criteria according to the rules of kata, c) the inherent limitations of human vision allowing a qualitative assessment, d) the quantitative contribution of the biomechanical analysis of the performance through the cinemetry, and e) its scientific absence in the biomechanical studies, this study aimed to evaluate kinematic characteristics of the gyaku zuki technique of jion kata karate style Shotokan. To characterize and compare kinematic variables of the gyaku-zuki technique (direct punch) in Groups 1 and 2: execution time, maximum linear velocity, and mean acceleration of the wrist of the law.22

This descriptive study was attended by 10 female athletes of the Shotokan style, selected by non-probabilistic sampling for convenience,23,24 in the purple, brown and black graduations that performed Jion kata for at least 1 (one) year, who have participated in at least one (1) state competition. The athletes of the Blumenau team were selected for obtaining a better ranking in the state of Santa Catarina in 2011 and representing both the State and Brazil in the competitions. They could not have musculoskeletal injuries in the last 6 months, and they should be training regularly. A kata was selected that did not present falls or executions in the ground, so that the inertial centers do not move in the body segment and also not to hurt the athlete. A kata competition was simulated to: a) evaluate the performance of the athletes during the execution of the gyaku-zuki technique (13th movement), of the first sequence of jion kata; b) to divide the athletes into two groups, according to their placement in the performance of the gyaku-zuki technique according to the performance evaluation by the referees: Group 1 formed by the athletes occupying the first 5 (five) positions places), and Group 2formed by the athletes that occupy the 5 (five) last positions in the evaluation of the referees (6th to 10th places).

The first sequence consists in executing the techniques: shuto age uke (high arm defense with open hand), age uke (high arm defense with open hand), ending with gyaku-zuki (counter punch with is ahead), object of this study. For this, the following collection procedures were adopted: a) Verbal guidance, to execute all the kata, with the same intensity and speed that the athletes perform in the training and in the b) Evaluation of the performance of the athletes by the referees only of the technique gyaku-zuki, of the first sequence of jion kata; c) At the end of the competition the central referee presented the classifications obtained by the athletes for the first sequence of jion kata. For the accomplishment of this study, a cadastral record was developed specially for this study, where data referring to the characteristics were collected. In order to acquire the kinematic data, the Xsens MVN Studio inertial motion capture system was used, which includes a software that allows real-time visualization and recording of the subject's 3D movement, as well as reproducing the recorded kinematic data of the biomechanical model with 23 body segments and 22 joints, including the center of mass. In this study the frequency of acquisition was 120Hz due to the studies on the basics of martial arts (kicks and punches) that used cinemetry.18,25–28 After approval by the UDESC Ethics and Research Committee with Human Beings (protocol no.10/2011), the referees, technicians and athletes were contacted and scheduled to start the collection, which was held at the Martial Arts Room of the Ipiranga Recreational Society (Blumenau/SC). The procedures adopted for the collection were: a) obtaining the signature of the Term of Free and Informed Consent; b) filling in the cadastral form; c) lottery of the order of presentation of the athletes. The athletes were prepared individually, wearing shorts and top and with the hair trapped. The routine adopted for each acquisition was: Preparation of the athlete: measurement and demarcation of the segmental points for fixation of the inertial centers in the body (Manual MVN Studio X-SENS).

Adaptation of the athleteSufficient period of adaptation of the athlete with the environment and instruments was made available. In this period the athlete executed the jion kata, at least 03 times, to adjust the inertial centers in relation to the segmental points. Heating: the athlete was available between 05 to 07 minutes, for the execution of exercises that routinely adopt for the competitions.

Calibration Standing the athlete has adopted 3 positions according to the system manual for system calibration.

Acquisition of the data properThe athlete positioned herself in the dojô awaiting the command of the general referee to start the jion kata. Given the command, the athlete performed the kata only once, with the same intensity and speed that he/she performs in the competitions (article V, number 3). The statistical treatment used to characterize the technical profile, and the kinematic variables of the gyaku-zuki technique, was the descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation). In order to compare the kinematic variables, average execution time, maximum linear velocity and average linear acceleration, between the two groups according to the performance of the first sequence of jion kata (Group 1: 1st to 5th position, and Group 2: 6th to 10th position ), the Student t test (unpaired) was adopted.

Characterization of the technical profile of kata athletes regarding the variables average training time and weekly training frequency, it was found that athletes black bands (9years, 5.5times a week) presented values higher than the athletes purple bands (5years, 4.33times per week) and brown bands (6years, 4.66times per week). Regarding the number of participations in competitions, all the athletes participated in state and national events, being at least 4 states and 1 national. The majority (6/10) participated in at least one international event. Characterization of the kinematic variables of the gyaku-zuki technique of jion kata of Groups 1 and 2.

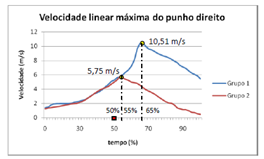

Analyzing the results of Table 1, it is verified that the athletes of Group 1 perform the gyaku-zuki technique in a shorter time (0.375s) than the Group 2 athletes (0.503s). Analyzing the characteristics of the maximum linear velocity between Groups 1 and 2 whose behaviors over time are illustrated in Figure 1a, Figure 1b it is possible to highlight that: a) Group 1 executes the technique with higher velocity (10.51m/s) than Group 2 (5.75m/s); b) Group 1 takes longer to reach the velocity peak (0.275s) than Group 2 (0.216s). In Figure 1b, which shows the behavior of the maximum linear velocity in absolute time, it is possible to emphasize that both Group 1 and Group 2 reach the maximum speed in the second half of the gyaku-zuki technique execution time (65% and 55% respectively).

Average linear accelerationAnalyzing the distribution of the values of the mean linear acceleration between Groups 1 and 2 in Figure 2, it is possible to emphasize that the athletes of Group 1 (4.94m/s2) presented twice the acceleration of the wrist during the execution of the technique gyaku -zuki, than the Group 2 athletes (2.38m/s2). Analyzing Table 2, there was a significant difference in all variables analyzed. Thus, athletes in Group 1 performed the gyaku-zuki technique in a shorter time (0.375s), reaching approximately twice the values of maximum speed (10.51m/s) and average acceleration (4.95m/s2) in relation to Group 2 (0.50s, 5.75m/s, 2.38m/s2), respectively.

Figure 1 Graphical representation of maximum linear velocity in Groups 1 and 2, in the gyaku-zuki technique.

Figure 1a Graphical representation of maximum linear velocity in Groups 1 and 2, in gyaku-zuki technique (%).

Figure 2 Graphical representation of the mean linear acceleration in groups 1 and 2, in the gyaku-zuki technique.

Variable |

Medical exercise time (A) |

|

Groups |

X |

4 |

Groups 1 |

0.503 |

0.03 |

Groups 2 |

0.375 |

0.07 |

Significant p<0.05 |

||

Table 1 Average execution time of the gyaku-zuki technique of Groups 1 and 2

Technique |

Gyaku-zuki |

|||

Variable |

G1 |

G 2 |

t |

p |

Average time(s) |

0.37 |

0.50 |

-3.56 |

0.007 |

Maximum linear speed(mis) |

10.5 |

5.75 |

1.39 |

0.002 |

Aceleracao linear media(m/s2) |

4.95 |

2.38 |

-1.22 |

0.025 |

Significant p<0.05 |

||||

Table 2 Comparison of the kinematic variables of the gyaku-zuki technique between Groups 1 and 2

Regarding the technical profile of the kata athletes, it was possible to find that the average training time of these athletes (6.9years) is apparently higher than the values found in the studies by Milanez et al.29 & Suwarganda et al.4 who were 2 and 3 years. However, numerically lower than the values of César30 and Santos31 that was 17 years and 9.5years. Therefore, it is verified that the athletes of kata have an average time of training intermediate to that referenced in the literature. Similarly, the values reported for the weekly training frequency of these athletes (4.9 times per week) are higher than the mean value found in the Suwarganda et al.4 Study, which was 3.7 times per week, and similar, in relation to athletes black belts, the training frequency of the athletes of the study of Milanez et al.29 which was 5 times a week. In relation to the number of participations in competitions, the studies do not specify the number, but the frequency with which they participate in them. As in the study by Milanez et al.29 athletes regularly attended state, national and international competitions, and in the Santos study,1 athletes often competed at the state and national levels, but without specifying the number. The number of these participations seems to be related to the characteristics of the team and the coach, where it is necessary to consider: a) the maturity, the readiness and the responsibility of the athletes; b) financial resources to fund the participation of these athletes in competitions: c) the number of state, national and international events that take place per year. It should be emphasized that these participations provide technical support for the technical execution of kata, as well as feedback to the training routine, identifying failures that could compromise the performance of the athlete and thus seeking the best performance in this modality.5 Regarding the characterizations and comparisons of the kinematic variables between the groups, the fact that the athletes of Group 1 performed the gyaku-zuki technique in a shorter time and with values of maximum speed and acceleration superior to the Group 2 athletes can be attributed to the technical characteristics of the first (higher training time and weekly training frequency), who obtained a better classification according to the referees' evaluation in the execution of the technique in jion kata. This reflects the profile of the most graduated athletes, who according to Nakayama12,14 can be represented by: a) degree of maturity, technical knowledge, serenity, discipline and responsibility of this range; b) level of collection by the technician, taking into account the graduation itself, the time available for weekly training, and the school performance; c) evaluation of the referees in the competitions and the requirements contained in the Kata Rules.30,31 In the literature, no studies were found mentioning the time of execution of the technique in kata, only in the kihon mode in which the times found were lower than the presented in this study, which were 0.19s32 and 0.27s.33 As for speed values, the literature recommends that the maximum velocity in the gyaku-zuki technique of the first jion kata sequence should be reached in a longer time, that is, in the second half of the technique execution time, after 50 % (Chart 1b). Since it is a finishing technique of the first jion kata sequence, it should have a higher peak at the end, characterizing the attack speed.5,14 Although kata is an imaginary fight, the athlete should emphasize the reality of a fight (kumitê), applying the techniques with maximum speed when aiming at the opponent's knockout, or when aiming at obtaining points or applying a surprise element. In order to compare the results of the maximum linear velocity of the gyaku-zuki technique, the studies turn only to the analysis of the technique as a component of kihon (technical foundation) and not kata. These studies only indicate the linear velocity between 6.1m/s and 8.5m/s20 and 13m/s,34 with no values being reported for linear acceleration. However, the comparisons between the values found in this study and the above mentioned studies are impaired. Even though the same analysis technique, the application is different according to the mode analyzed (kihon and kumitê). Therefore, the values presented here serve as the basis for future studies with the kata technique. It can be said that when the variables run-time, maximum linear velocity and average linear acceleration between groups are compared, the first group reflects the technical level and performance in which they are. These results corroborate with the literature,5,12,14,33,35‒38 whose objective is the achievement of high individual performance, optimizing the increase in volume and intensity of training, in search of perfection, stabilization and maximum availability in the execution of kata.

None.

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

©2018 Martins, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.