Journal of

eISSN: 2574-8114

Artefacts in the form of Jewellery reflect the essence of the lifestyle of the people who create and wear them, both in the historic past and in the living present. They act as the connecting link between our ancestors, our traditions, and our history. Jewellery is used--both in the past and the present-- to express the social status of the wearer, to mark tribal identity, and to serve as amulets for protection from harm. This paper portrays the ethnic ornaments of Kerala with insights gained from examples of Jewellery conserved in the Hill Palace Museum and Kerala Folklore Museum, in Cochin, Kerala. Included are Thurai Balibandham, Gaurisankara Mala, Veera Srunkhala, Oddyanam, Bead necklaces, Nagapadathali and Temple Jewellery. Whenever possible, traditional Jewellery is compared with modern examples to illustrate how--though streamlined, traditional designs are still a living element in the Jewellery of Kerala today.

Keywords: ethnic ornaments, Kerala jewellery, sarpesh, gowrishankara mala, veera srunkhala

Every artifact has a story to tell. The stories are our connecting link with our ancestors. They carry in them an unbroken, living tale of our culture in wearable art.

It can be said that wearable artifacts offer a record of our social history. More than that, they embody the imperishable, still growing, and sacred root of our cultural identity. For millennia, we have used wearable ornament to tell our human story by designing it to transmit a social message. We still use the Jewellery we wear to mark our tribe, signal our status, make a statement about our inheritance and wealth. When we combine it with folklore and magical thinking, we still use it to protect us from bad luck or the forces of calamity.

Primitive man believed that spirits in material objects endowed the inanimate Jewellery with soul, and that belief has lingered--resistant to the passage of time. For example, ever since pre-history, artisans in India have made tiger claw Jewellery to give the strength of the tiger to young male children. The practice--though modernized--is still alive today.1 Contemporary brides in Kerala often wear modern gold versions of the three traditional gold marriage necklaces (mangkaliyam anivadam) that include tiger-claw shaped units (pulinagathali).2 Though the use of animal parts originated with magical thinking, the soul of that belief--that need for protection--lives on in the DNA of contemporary Jewellery design.

The motifs of Kerala live on, morph, and narrate the unbroken story about culture. The hopes and fears of people are reflected in adornment.3 The need to express identity--the desirability of wearing a ‘fashion statement” impels modern people to buy, wear and make Jewellery, irrespective of circumstances or caste.

In the parlance of the study of archaeology, Jewellery is called a “special find” because it is one of the best indicators of economic, social developments of any period. According to Norbladh, the discussion on Jewellery and gold objects gives voice to the political and social dynamics of both the culture and the technology of its moment in history.4

Indian cultures have used Jewellery as a strong medium to reflect their rituals. The design motifs depicted on the ornaments of India indicate their worship of the serpent, the moon, and the sun. Although the prevalence of any given design motif differs from place to place, good luck charms were ubiquitous, worn not only for adornment, but often for their religious and superstitious significance. Marriage ornaments symbolize troth, and differ from place to place.5

The evolution of methods for making Jewellery tells the story of social and technological development. Materials and methods have streamlined over time--but the design motifs that are peculiar to Kerala have held onto their traditional presence in Jewellery. This presence--melded with the spirit of the living moment, helps traditional design become an undeniable element in the contemporary Jewellery art of the region. It is noted that little research was done on the ethnic ornaments of Kerala. This paper aims to depict how the human attachment to tradition, the need for protection, social status and even love are expressed in the thematic choice of the abstracted motifs that run through time in the Jewellery of Kerala. The paper also focuses on revealing the cross-cultural influence on design and techniques of Jewellery making, and its main contribution will be to point out that Jewellery is the living, unbroken record of cultural identity.

Primary and secondary research was conducted by the authors to collect information on the ethnic ornaments of Kerala. The collected information is based on the Jewellery in the Hill Palace Museum and the Kerala Folklore Museum in Cochin, Kerala. These surviving examples are the accidental, precious survivors, dating from as early as 1000 B.C.E. Both museums have a significant part in conserving the most important artefacts of the area. The support museums render to scholars actively disseminates that cultural knowledge to present and future generations.6 Their work in conservation links thousands of visitors annually with their living cultural heritage. The Hill Palace Museum is operated under the auspices of the Department of Archaeology, in the Government of Kerala. It was originally built as the royal residence of the Kochin Kings. The historical significance of the palace is magnified by its architectural beauty and the treasure displayed in its galleries--amassed over generations by the Kochin royal family.7

The Kerala Folklore Museum, in Thevara, Kochi is an architectural museum that houses a collection of more than 5000 cultural artefacts from the region. (and beyond). Both the Hill Palace Museum and the Kerala Folklore Museum are invaluable cultural resources for researchers, art lovers, and travelers from India and internationally.8

Every journey begins with a single step. Our narrative begins with a discussion of the earliest Jewellery found in Kerala. There are many gaps in the historical record of leading up to the 21st Century. One reason for this could be that perhaps design motifs evolved so slowly that they are indistinguishable from one Century to the next, making comparison impossible.

The stone bead necklace dating circa 1000 B.C.E. displayed in the Kerala Folklore Museum is threaded with hard, semi-precious stones. Ancient people might have valued these stones for their hardness, degree of translucency, the unique qualities of their patterned surface, and their color. The human proclivity to consign meaning to unusual things ties into our innate curiosity and our attraction to the rare and precious. As a young mother, watching the children play near a pond, I was often witness to this--when my son would joyously show me a beautiful wet rock, eroded smooth by the sand and water. In the eyes of a child, it was precious. And if I encouraged him to tell me a story about it, he would have told me it was magic.

We cannot say for certain why and how the stone beads were selected for this necklace. There is no written record to tell us if these particular stones were ascribed with magical qualities. What we can say is that hard stone beads, worn as ornaments, are likely the earliest amulets fabricated by man. The archaeological excavations at Mohenjo-Daro, Indus Valley Civilization, and other sites provide the physical evidence that the manufacture and trade of agate, carnelian, crystal, and other hard stones existed as early as 1000 B.C.E.2

Evidence of the export and trade of Gujarathi hardstone by the Babylonians (by setting the agates in finger rings) is supported by Pliny, AD.77. The present-day bead manufacturers in India still follow the same process practiced during Neolithic times. Khambhat, in Gujarat has been connected with the hard bead making industry for more than five thousand years. The beads in the necklace depicted in Figure 1 resemble banalingas, (made for Shaivite workshop) prepared out of agate and red stones (svarnabhadra) manufactured by the artisans of Khambat, Gujarat.2

The chief source for hard stones used in bead making are the deposits of Agate/chalcedony laid down during Mesozoic Era near, in, and around Baroach and Khambhat location, Gujarat. The beautiful variety of colors in these stones is derived from the presence of metallic oxide in the agate--manganese, iron, nickel, and copper.2

The history of glass beads in India began in the fifth Century B.C.E. The earliest examples have been discovered in great numbers in Taxila. In south India, beads made from other materials were also discovered in great numbers. These included beads made of magnesite, gold, shell, terracotta, agate, carnelian, glass, jasper, and steatite-- the same materials which were used in the Indus civilization.9

The gemstone necklace represented in Figure 1c is an example of a hard stone, beaded necklace manufactured in the 21st Century.10 Techniques have evolved--gold has replaced the cord that was used to string the ancient stones. Modern tastes have tended toward more elaborate ornamentation. But the similarity in structure is clearly evident. A “family resemblance” between the two necklaces has spanned the centuries.

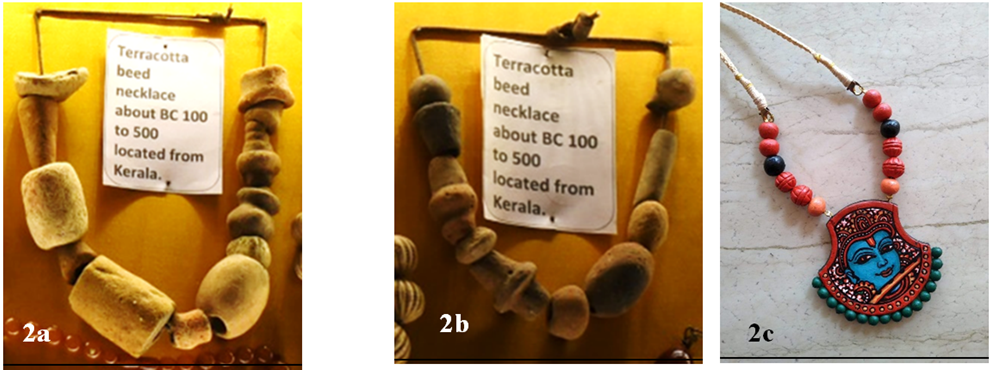

Terracotta is technically the term applied to fired, unglazed clay artefacts. But symbolically, in India, terracotta embodies the five elements (pancha-bhoota), earth, water, air, fire and aether.11 In these terracotta ornaments of 500-100 B.C.E. from the Folklore Museum, terracotta has been molded into beads and tubes, threaded together on a string. The inspiration for the forms is a matter of conjecture, but their shape calls to mind seeds or possibly bones. Beads molded into a tubular structure with spiral turns on the surface resemble a common seashell called auger.

The existence of terracotta in ancient Kerala was confirmed when terracotta idols washed up on the riverbanks of the Pamba river basin after a flood in August of 2018. The idols found then were representations of Sapta Kanyas (Sapta means seven and Kanyas means virgins) and that of a male figure and a serpent figure.12

Terracotta Jewellery is still popular in Kerala, and the imagery has evolved through time. 21st Century examples have retained the bead forms and added images borrowed from the mural paintings in local temples. The necklace pictured in Figure 2c is an example of one of the most popular trends prevailing in Kerala Jewellery today. This 21st Century example is made with multi-colored beads and a semi-circular shaped terracotta pendant, decorated with a painting of Lord Krishna, inspired by a temple mural. The necklace is strung on a thread. (Matching earrings, not shown here, are available and conform to modern tastes).13

Figure 2 Terracotta Bead Necklace. 2a and 2b: B.C.E. 100 to 500, 2c–21st Century. Terracotta necklace.

Source: 2a and 2b: Folklore Museum, Kochi, 2c. Design courtesy: Gopal (2019), facebook page.13

The existence and juxtaposition of these two examples, ancient and modern, confirms that terracotta is an art form that has been passed on from generation to generation, spanning the centuries. The imagery has evolved to reflect the tastes of the present day, but in Kerala, the use of the terracotta--representing the five elements--earth, fire, water, air, and aether--is still--undeniably--a living tradition in wearable ornament.14

Thurai balibandhanam

The Thurai Balibandhanam exhibited in the Hill Palace Museum dates back to the 18th Century, and is also known as Sarpesh (Figure 3a). A Sarpesh was worn on the headdress by the King of Kochi, and wearing one was a signifier of the social status for men during that period. It was reported that the Nizam of Hyderabad also used this kind of head adornment in his ceremonial regalia.15 The design resembles a pine or cone-shaped top with three plaques; a round central motif flanked by two side plaques. The piece is encrusted with diamonds, rubies, and pearls set in gold and a cable pattern of filigree.16 The embellishment for turban, Sarpech or Shirpej has evolved and reached during the medieval period and reached its perfection during the reign of Moghuls and Princes of Rajasthan.17

Figure 3 3a: Thurai Balibandhanam, 3b: The Sarpech.

Source: 3a: Hill Palace, Published by the Dept. of Archaeology, Kerala Govt., 3b: Untracht,2

The dressing of the head was an important part of the presentation of the royal Indian prince. In particular, the Sarpesh, or jewelled head ornament, complete with a jigha or aigrette, had an interesting development. Originating with the ancestors of the Moghuls as a plume of owl feathers, the ornament was adapted in India, where the emperor wore egret feathers, weighed down by pearls, in his turban. This plume was also realized in jeweled form, possibly inspired by European jewel-encrusted brooches, which were known at court and were given out to nobles as symbols of princely recognition.18

The Mogul influence is evident in Thurai Balibandhanam. Rubies in Mogul Jewellery from circa 1500 display evidence of the European practice of putting gold foil under the settings. The purpose of the foil was to enhance the brilliance of the rubies, causing them to reflect more light. Benvenuto Cellini (Italian master jeweler, 1500-1571) described this method for using gold foil in setting rubies in his Treatise on Goldsmithing and Sculpture. According to Cellini: A piece of foil large enough to fill the cavity of the setting was pressed into the bottom of the setting with a clean, dry, blunt-ended punch. The foil was held in place with a little cement spread on its back. Sometimes, the foil was first pressed around the bottom surface of the stone, which was then set. In a completely closed cabochon setting, the foil was sealed from atmospheric contamination. If non-oxidizing, pure gold was used, the foil can theoretically remain bright for centuries.19

Conservation of these jewels requires a careful analysis of the composition of the adhesives and a fore-knowledge of the presence of the foil. Wet cleaning processes, done heedlessly, can compromise the setting and spoil the effect of the foil.19 It is very interesting to note that in Agra, the intarsia cutters and stone in-layers credit the recipe for the cement they use to an Italian jeweler employed by Shah Jehan (1592-1666) in conjunction with the construction of the Taj Mahal. There is no hard-documentary evidence to support this sharing of recipes, but a jeweler named Geronimo Veroneo did live in Agra during the construction and doubtless brought with him Italian stone setting and intarsia techniques. The giant intarsia in-lay on the Taj may have been inspired by the beautiful, intricate inlaid table and architectural interior accents that were in fashion in Italy at the time.20,21

To this day, rubies in some Indian Jewellery are still set with foil backings. Lac and even the recipe for intarsia cement are used when rubies are set into another stone--often jade. This method of setting rubies with gold foil is still practiced the same way today as it was during the reign of Shah Jehan in the 16th Century.22

The symbolic, traditionally held belief in the healing properties of rubies has made them a popular gem for ethnic Jewellery. Red, the color of rubies, is considered to be a warm, aggressive color among Hindus. It symbolizes the intensity of the sun, blood, and sensual emotion--all of which are essential to human life. The ruby has retained its position in Indian Jewellery through the centuries through the tenacity of these traditional beliefs and its symbolic connection to Surya, the sun god--the sun being the giver of light and warmth--as well as being the center of our solar system. In gem therapy, rubies are used to treat blood diseases such as anemia, heart diseases, and illnesses of the circulatory system. They are also believed to have the power to break fevers and to prolong life.2

Veera srunkhala

Veera Srunkhala (18th Century) exhibited at Hill Palace Museum is the symbol of valour and was presented by kings to courageous soldiers. This gold-plated bangle on silver is studded with rubies in four concentric circles. The width of the bangle is about 2.5cm, and it has a hinge at the sides. The hinge allows the bangle to be opened and locked while wearing. It also allows the removal of the bangle. Very little is documented in literature about the origin of this valuable piece of artwork (Figure 4).

The technique used for applying gold to this bangle is called mercury amalgam gilding. Theophilus the Presbyter (c. 1070-1125) described the technique in his treatise: On Divers Arts. Before the advent of electroplating, amalgam gilding was the best way to clad a piece of silver with gold. In this effective but dangerous process, mercury is dissolved in nitric acid and heated--then added to gold and applied to a prepared silver surface. It has enjoyed something of a revival today, although the process is so toxic, it is primarily practiced in workshops where government safety regulations are not enforced. Also called “fire gilding”, mercury amalgam gilding is still widely practiced in the East, especially on ritual objects and images of deities.22

When describing the process, Theophilus warns: “Be very careful that you do not...apply (mercury) gilding when you are hungry, because the fumes of mercury are very dangerous to an empty stomach and give rise to various illnesses against which you must use zedoary, turmeric and barberry, pepper and garlic and wine”.23

In mercury gilding, the gold takes a firm hold and actually soaks into the silver surface, creating a thick coating of gold. Because the gold deposited is more than thin skin, it is tenacious--and highly resistant to wear over time. The process requires that pure gold is used, which makes the piece resistant to oxidation. Untracht says that…” gilded articles excavated by archaeologists have (been unearthed) in a well-preserved condition because of their surface gilding”.22

Silver necklace

In India, silver is the symbolic metal that represents the cool color of the moon. It is a quintessential metal used in Indian Jewellery. The silver necklace displayed at the Kerala Folklore Museum depicted in Figure 5a is an 18th Century example of silver neck ornamentation. The brown color it exhibits in the photograph comes from tarnish, or oxidation that has accumulated over time. The original color would have been a cool, white metal hue. The design involves the repetition of five pendant units of similar dimension, threaded on a cord. Each pendant is a separate piece of silver. The distance between them is maintained by knots in the cord. The shape of the pendants resembles seeds--a recurring motif in traditional Jewellery. Small dots (one center dot surrounded by six dots) make up the design, notably on the center and on the top part of each pendant. Smaller dot patterns embellish the lower edges of the design.24

Figure 5 5a: Silver Jewelry, 5b, 5c: Arapatta/Odyanam (Linked belts) 18th Century, 5d. The waist belt and 5e: Kerala bride.

Source: 5a.5c: Folklore museum, Kochi, 5b:,2 5d and 5e: Bhima ornaments.

Arapatta/Odyanam

Arapatta/Odyanam (kheki) is one of the oldest forms of wearable ornament. In India, belts decorated with cowrie shells (asiasakikheki) often included ornamentation with red-dyed goat hair and yellow orchid stems. Men’s waist ornaments decorated with cowrie shells (lapuchoh kuhu) were traditionally the sign of a warrior and were reserved only for those who earned the right to wear them--either by inheritance, social position in the tribe, or by achievements in battle or in raids.2

The silver belts, dating from the 18th Century, exhibited at the Kerala Folklore Museum (Figure 5b and Figure 5c) were worn by the Muslim women of the Kozhikode region of Kerala.9 Their design consists of double interlocking wire links with a buckle and hooks on either side. The belt closes by passing the end through the buckle, then engaging the inverted hook into the chain links.2 The buckle and hook parts are elaborately decorated with woven wire.

Similar kinds of belts and hip-chains are still used by women all over India with style variations from region to region. But one famous historical example of a belt is found on the statue of Yakshi, the fertility goddess (generally called a “fly-whisk” ((chauri) bearer), dating from the Maurya Period, 3rd Century B.C.E. The statue, carved from soapstone, shows the goddess wearing a Kamardani (a five-chain belt with lotuses in profile on the clasp).2 A similar kind of waist belt, known as Odyanam, made of silver wire plated over with gold is exhibited at Hill Palace Museum. That belt was worn by the female members of the Kochi Royal family.25

Figure 5d and Figure 5e depict 21st Century waist belts made out of gold worn by brides of Kerala.26 The wearing of hip chains as an ethnic ornament has been a traditional practice during marriage and festive occasions in India from 3rd Century B.C.E., all the way up to the present day. This unbroken continuity in the design and the ethnic use of belts made of precious metals testifies to the tenacity of cultural influences in wearable adornment in India.

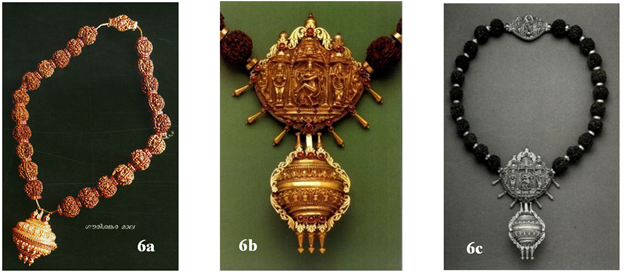

Gowrishankara mala

The Gowrishankara Mala from the 19th Century, exhibited at the Hill Palace Museum is an example of Rudraksha chain--a chain made with the seeds of Elaeocarpus ganitrus. This Gowrishankara mala is a neck ornament worn by the Kings of Kochi during the 19th Century.15 As the name indicates, Gowri means Lord Parvathy, Shankara stands for Lord Shiva, and mala means chain. In the name, “Rudraksha”, Rudra means “Lord Shiva”, and Aksha means “eyes”.27 The seeds alternate with spacer rings studded with rubies. The pendant encompasses a small “Gowrishankara” idol. The type of Rudraksha beads used for making Gowrishankara Mala was panchamuki (five faces). Oppi Untracht mentioned that this form of Jewellery is also known as rudrakshamali or linga padakka muthu malai, and it is worn today by Shaivate priests and by men over eighteen years old.

In contemporary examples, Rudraksha seed nuts are still-threaded in the same method, alternating with gold spacer beads. A gold clasp is attached at the back. The central unit represents the Shiva Nataraja Dance, known as “Shiva Thandava” representing the concept of uninterrupted creation, maintenance, and destruction (Srishti-Sthithi-Samharam). This ruby studded pendant contains a movable lingam and sacred ashes or vibhuti from ritual fire or cremation grounds. Vibhuti is the ash used by Lord Shiva to smears his body. This practice is still followed by sadhus, yoga practitioners, and devotees in the 21st Century (Figure 6).2

Figure 6 6a,6b, 6c: Gowrishankara mala - Kochi Royal family. Gowrishankara Mala (Gowri=Lord Parvathy, Shankara=Lord Shiva, Mala=chain).

Source: 6a: Hill Palace Museum, Published by the Dept. of Archaeology, Kerala Govt. 6b, 6c.2

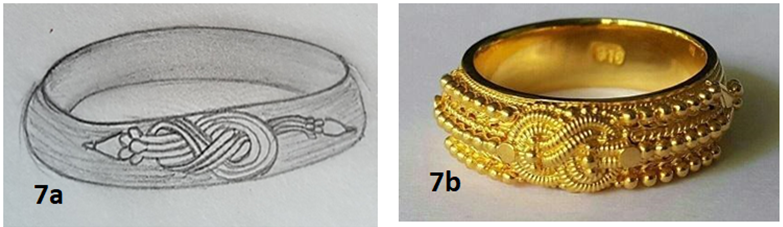

Pavithra ring

This gold pavithram ring at the Hill Palace Museum (depicted on the left) was used by the Kochi royal family during the 19th Century (Figure 7a). The title for this ring/ornament style is Pavithra mothiram; “Pavithram'' is the Sanskrit word meaning “holy”, pure or sacred. “Mothiram'' is the word for “finger ring”. The design motif on this ring is an abstraction of the darbha grass or kusha grass, and its traditional religious significance invokes protection for the wearer. Darbha grass (Demostachya bipinnata), is the most sacred among all Indian grasses and is considered to be sacrificially pure. Hindus believed that it was the first plant created by Gods. They believe it has the power to purify everything it touches. A pavithram ring made of dharba grass is used in all the Hindu rituals and on auspicious occasions.

Figure 7 7a: Visual representation of Pavithra ring worn by the Kochi Royal family exhibited at Hill Palace Museum, 7b. Contemporary designs of Pavithra rings of 21st Century.

Source: 7a: Hill Palace Museum, 7b: www.pavithramothiram.com.30

During religious ceremonies, it is customary to wear the Pavithram ring on the right hand, third finger. It is believed to possess the power of an amulet--to frighten away evil spirits.2 The knot that is represented in this ring is known as “brahma grandhi”, a psychic knot. Through the preparation of spiritual practice, a yogi learns to untie this knot for releasing kundalini. The ring is made by twining and winding thin gold wires to form knots. While making the rings, the craftsmen must follow certain spiritual disciplines: they must be teetotallers and pure vegetarians.28

The pavithram rings found in Kerala are unique and very unlike the interwoven knotted forms found in other regions of India. Rings originating from Kerala are formed like two V's joined at the tops. This motif might be inspired by “Vanki”, Tamil upper armlet. The three layers in the design of pavithra ring represent three nerves on the human body that is Pingala, Ida, and Sushumna. Hence it is believed that wearing a pavithra ring bestows purity, spiritual and mental health to the wearer.29 Both of the rings pictured here--the traditional example from the Hill Palace Museum and the 21st Century version--has the three-strand motif as the central element of the design.30

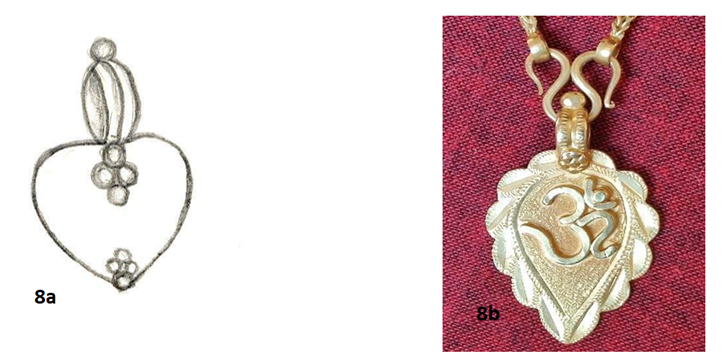

Thali

In most parts of the southern states of India, the mangalasutra are also known as a thali. The thali is the marriage insignia for Indian brides. It consists of oblong pieces of gold rounded at one end and strung together by a thread. The thread is made out of 108 fine cotton yarn threads and dipped in turmeric. The Sanskrit word Mangal sutra signifies happy, successful, prosperous, and blessed sutram means cord. The thali is tied around the bride's neck with three knots. It symbolizes that the bride and the groom are united, and they need to take care of each other. It also represents the inseparable amalgamation between Lord Shiva (husband) and Shakthi (wife).5

The three knots represent the three aspects of commitment, manasa, vachaa and karmana, meaning --believing it, saying it, and executing it. The knots also represent different aspects of the body. These are the physical body--sthula sharira; the spiritual body-- sukshma sharira; and the casual body—the kaarana sharira. The mangalsutra (as an ornament) is also considered a talisman to prevent the evil eye.5

Among the Nair people of Kerala, the term thali retains its ancient connotation and is used synonymously with the ‘mala’, referring to a necklace. The Kerala Hindus also use thali, which in Kerala is also called ela thaali-- meaning the shape of a leaf --or bearing the design of a leaf worn by married women. The ela thaali generally displays the Sanskrit syllable ‘Om’ embossed or cut-out on the leaf-shaped gold sheet. According to Indian tradition, married women in India wear mangalsutra around their necks for their entire married lives. It is believed that by wearing a mangalsutra, a wife can summon the energies of the universe to pray for a long life for her husband (Figure 8).5

Figure 8 8a. Thali sketched from the Hill Palace Museum, 8b. Thali used by Hindus.

Source: 8a: Hill Palace Museum, 8b: Authors personal collection.

Nagafanathali or Nagapadammalai

“Ophiolatry” or snake inspired motifs are one of the frequent forms of ornament in Indian ethnic Jewellery (snake forms include sarpa, nag, or panbu.). The tradition of wearing Jewellery representing symbolic or the actual form of snakes may have originated with their worship as sacred deities. Cobra or Naja tripudians with expanded hood is one of the most commonly represented in Indian Jewellery. A beautiful example of 19th Century Nagafanathali that was worn by the Kochi Royal family exhibited at the Hill Palace Museum is depicted in Figure 9a. In the name “Nagafamathali” Naga means snake, and Fanam or Padam mean “hood”--the hood of the cobra. In this necklace, the middle piece is slightly larger than the 27 units on either side of it. Each piece is made of gold and contains a cabochon ruby. A gradation in size was observed from the middle part towards the upper edge. Every single unit threaded in the left side represents an exact mirror image of the right, separated by the centrepiece.

A similar necklace shown here is called “Nagapadammali”. The name means “Snake hood chain”. The style is a style variation of the “Nagafamathaki” in Figure 9b. This piece is housed in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. It is comprised of 45 stylized cobra heads–each embedded with cabochon rubies and emeralds.2 The oldest and the most famous ornament of the Nair women is the nagapada thaali or the cobra hood necklace. Nair women believe that this was given to them by the gods to grant them the virtues of patience and calmness.5

Kasumala

In Hindu belief, Gold is a sacred metal that symbolizes the warmth of the sun. Hindu tradition associate’s gold with immortality. The obvious reason for this is that gold never oxidizes or corrodes, and it does not diminish during prolonged storage—even if it is buried or stored for centuries.2 The use of silver or gold coins is prevalent in Jewellery in almost all parts of India, dating back to Sah dynasty, 180 B.C-50 B.C). In modern India, the use of coins in Jewellery signifies wealth, prestige, and it signifies the support for the prevailing government.2

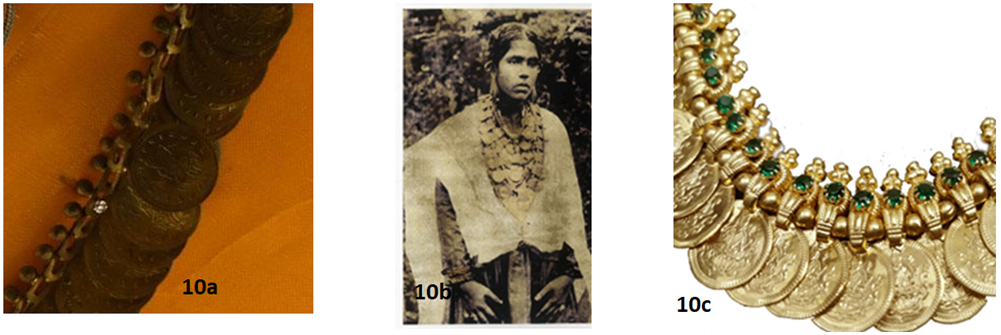

Figure 10a denotes the Kasumala exhibited at the Folklore Museum, in which every single coin is threaded to make a chain. Hindus, especially Nair women, adorn themselves with Kasumala that depicts Lord Lakshmi Devi engraved in each coin. According to Hindu belief, Lord Lakshmi brings wealth and prosperity.

Figure 10 Kasumala: 10a . Christian bride wearing Kasumala 19th C, 10b. 21st Century Kasumala.

Source: 10a. KeralaFolklore Museum, 10b. Thaliath,24 10c. Authors personal collection.

In the Jewellery gallery at Hill Palace Museum, a gold chain of Venetian coins is on display. This beautiful example (Vilkasumala), is threaded with 16 units, each about 2.5cm length and 2cm width, threaded in a gold coin. Another example, this time a Kasumala of 21st Century is represented in Figure 10c in it, the coins embossed with Lord Lakshmi make up the body of the chain, with green stones studded on the upper tips of the coins. These examples are indications of unbroken taste for coin Jewellery as symbols of status and wealth in Kerala from 50 B.C to the 21st Century.

Kattapoothali

The thali is the primary southern marriage ornament made out of gold. Thali is a Sanskrit word evolved from the dialect name of palmyra palm (thala; Borassus flabelliformis). In olden times it was mandatory to indicate the marital status of women by tying a palm leaf strip around her neck. A thali can vary in size from small to huge and can vary in form.2 Figure 11a and Figure 11b represent the images of Kattapoothali of the 19th Century exhibited at the Folklore museum and 21st Century, respectively. This Jewellery has 30 repeating units, studded with rubies, intricate designs, and small beads hung on the bottom edge.

The origin of Temple Jewellery was during the period of the Chola dynasty, 9th Century, B.C.E.31 Then and now, temples of any size possess a treasury, and in it are kept donations, often in the form of Jewellery. The outstanding features of Temple Jewellery include a regal look, craftsmanship, and richness which reflect the skills of Indian artisans. Dr. Usha R. Bala Krishnan, an art historian, and expert in the field of ethnic Jewellery, writes that the style and craftsmanship of temple Jewellery evolved to create Jewellery to adorn the statues of deities in temples. She opines that the tradition began with gifts of Jewellery intended as offerings to the gods from royalty and wealthy temple patrons. Temple Jewellery is also known as Kemp or Vadasari. The goldsmith and jewelers of Vadasari, a place near Nagercoil, Tamil Nadu, India, had honed the technique of producing the best temple Jewellery embedded with cabochon rubies, emeralds, and uncut diamonds.32,33

The chief source of the accumulated wealth of the temple is related to the Hindu practice of pilgrimage. Pilgrims visit a temple for spiritual reasons, to help them achieve salvation. Sometimes, the motivation for a gift to the temple is to solicit divine intervention in daily life. Requests often include pleas for help and trace the entire scope of human desire and suffering. Donations are given as offerings to beseech a God or Goddess’s help in removing obstacles in business, relief from illness, a happy marriage, assistance in the bearing of a male child, etc. At the end of life, a donation might represent the pilgrim’s willingness to relinquish earthly possessions and contribute to their final peace of mind.

Valuable offerings of Jewellery embedded with precious gemstones, gold, and silver are accepted. But when Jewellery of lesser value is donated, the temple authorities, with the help of a goldsmith--recycle it to create a new ornament. This recycled Jewellery is used to adorn temple deities, personified in sculpture. Even though it is made from recycled metal and gems of lesser quality, the dramatic effect of this Jewellery is visually striking. It helps create an atmosphere of religious theatricality in the temple that enhances the ethereal grandeur of the pilgrim’s religious experience as they worship.2

The necklace represented in Figure 12 illustrates the richness of the temple Jewellery designs of the 19th Century. Red and green gemstones adorn a beautiful pendant, enhanced with hanging pearls. The design motifs are inspired by nature. The gemstones are arranged in the shape of petals in flower and leaf patterns. Peacock feathers are the prevailing motif of the beautiful necklace (12a–12c), pathakka (pendant–12d,12e), and the dangling Jimikki (12f) exhibited in the Folklore Museum. Figure 12b represents a necklace of 21st Century Temple Jewellery designs. These examples help to illustrate how--though streamlined to suit modern tastes, not much evolution has occurred in the motifs, styles, and design. This fact supports the contention that traditional themes for ornamentation are very much alive in contemporary Jewellery design.34,35

The concept of traditional Kerala Jewellery is based on nature, mostly grass, seeds, fruits, flowers, leaves, animals, celestial bodies, and Hindu mythology. The design traditions in the Kerala ethnic ornaments are indelible--unmoved by the ever-changing trends of fashion. While observing the traditional ornaments from past forms to 21st Century contemporary styles, it is obvious that traditional techniques and themes are strong enough to influence 21st Century fashion. The traditional materials still make their presence felt in 21st Century Jewellery--copper, iron, agate, terracotta, pieces of bones appear in fact or in facsimile. Ivory and tiger claws are represented in imitation materials, and in designs made in gold, silver, gems, coral beads, and pearls. The Jewellery found in temple ornaments and in contemporary Jewellery design supports this inference.

The design and techniques used in south Indian Jewellery still show a touch of design inheritance from prehistoric Jewellery making techniques. This is evident from Jewellery depicted on sculptures. The basic design of Kerala traditional Jewellery is very simple and until the 11th Century, consists of beads, short and long cylinder forms, and floral pendants. After the invasion of Mughals in India, the base form of the Jewellery remained the same but the finish and details became more elaborate. It was during this period that the Jewellery reached the height of perfection in aesthetics and detailed craftsmanship. Enamelled Jewellery and Kundan technique became popular during the Moghul period. Plain traditional motifs found new expression--studded with precious stones and pearls.9

The Jewellery seen in the Southern Indian and Northern Indian states had many common design elements during that period--but in the north, the use of enameling and Kundan is prevalent. By contrast, the form and structure of Kerala Jewellery remains simple, and the amount of enameling and Kundan work is less evident when compared to the Jewellery of North India.

Jewellery is one of the inseparable components of Kerala's culture and tradition. Jewellery is worn not only for aesthetic purposes; it is also associated with culture, religion, and protection from evil spirits and calamity. Each occasion in the life of a person is associated with Jewellery. It begins with the first piece of Jewellery in a child’s life--when parents tie a black thick cord and gold chain around the waist of a baby during the 28th day after birth. Later, the child’s ears are pierced to wear earrings. Little boys are given amulets with representations of tiger claws and Jewellery made from tied and braided elephant hair to protect them from evil and help them attain strength. Jewellery is the standard gift to children as they make the transition from child to adult in puberty. The Pavithra ring worn on the right-hand ring finger during rituals indicates the spirituality and faithful observance of religious customs. The thali tied to the bride’s neck by the groom on the wedding day retains its significance to this day.

Veera Srunkhala is a type of Jewellery that was traditionally gifted by the king to brave warriors as a symbol of courage. Owning and wearing Veera Srunkala distinguished a man from all others, and has evolved into a status symbol marking outstanding achievement. Gowrisankara Mala, made with Rudraksha beads and the pendant with a small idol of Goddess Parvati and Lord Shiva, still symbolically represents the concept of “Ardanaseeswara”, the harmony of male and female--and it is worn in various forms to this day. Sarpech, embedded with diamonds and rubies, were originally worn as a royal symbol in the turban of the king. In modern India, the Sarpech is still seen in the turbans of grooms. It can be argued that the Sarpech form of ornament was the first type of Jewellery to be used as a signifier of the social status of men in India.

Thus, the motifs of Kerala live on, morph, and narrate the unbroken story about culture and the hopes and dreams of its community. The comparison of the Jewellery between the 18th-19th Century and 21st Century signifies that the people of Kerala still value for their culture and still love to adhere to their roots and tradition. Even though techniques and lifestyle change, the desire for novelty in design and a sense of belonging to one’s own cultural tradition exist side-by-side given equal priority.

The human need to express identity has not changed since prehistoric times. The spirit of the ethnic Jewellery design of Kerala is at present enjoying its reincarnation in the 21st Century as a “fashion statement.” And the cultural desirability of wearing a ‘fashion statement” impels modern people to adorn themselves with these beautiful ornaments--making them ever-new--irrespective of wealth or caste.

The authors acknowledge Mr. Reji Kumar J, Director, Department of Archaeology, Govt. of Kerala, and Mr. E. Dinesan, Publication Officer, Hill Palace Museum for granting permission to collect information on the precious Jewellery exhibited at Hill Palace Museum, Kochi. We are also thankful to the authorities of Folklore Museum, Kochi for giving vast information on Kerala ethnic Jewellery and Authorities of Bhima Ornaments for permitting us to use the photographs of ornaments from Bhima Jewellery’s online sources.

None.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in publishing articles.

© . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.