Journal of

eISSN: 2373-4310

Research Article Volume 4 Issue 2

Clinical Dietetics Department of Nutritional Sciences, Howard University, USA

Correspondence: Chimene Castor, Howard University, Clinical Dietetics Department of Nutritional Sciences, Division of Allied Health Sciences, Washington DC 20059, USA

Received: January 07, 2016 | Published: February 29, 2016

Citation: Smith-Hawley M, Taylor, Johnson, et al. Nutritional interventions for addressing the health disparities of obesity in a clinical setting. J Nutr Health Food Eng. 2016;4(2):372-377. DOI: 10.15406/jnhfe.2016.04.00121

Introduction: A dramatic rise in obesity rates with a corresponding increase in disparities across socioeconomic groups have been progressively reported and well known in the past three decades in the United States.

Objectives: To identify and address the etiologies and socioeconomic health disparities that influences the ongoing; increase in obesity within the United States of America and related altered nutritional status. To address the health disparities of obesity using evidence-based guidelines of Medical Nutrition Therapy; recommend nutritional interventions that promotes weight improvements and BMI within healthy weight range.

Methodology: Study Design: Application of the Nutrition Care Process (NCP) to collect, organize and evaluate data using the Assessment; Diagnosis; Intervention; Monitoring and Evaluation (ADIME) format. Study Population: This case presentation involves one obese adult patient (MJ) in a clinical setting. Data collection via reviewing the patients’ electronic and medical records; interview with the patients and/or the patient’s caregivers and registered nurses to ascertain: usual dietary habits; food preferences; food accessibility and availability; identification of possible barriers to food security. Nutrition counseling via application of The Trans Theoretical Model-Stages of Change was applied in nutritional counseling to impart knowledge on the health benefits associated with making lifestyle modifications.

Results: Utilizing strategies like the provision of nutrition education to promote lifestyle and environmental changes such as healthy eating and active living; as well as addressing the existing barriers to intervention such as food security; and imparting information about ways to effectively utilize available resources can help to reduce the health disparities of obesity.

Conclusion: Although the nutritional interventions recommended to address the health disparities and minimize the risks of Obesity did not reach statistical significance, the clinical and nutritional implications warrant further investigation.

Keywords: health disparity of obesity, clinical nutrition, inpatient, avascular necrosis

NCP, nutrition care process; WHO, world health organization; ASBP, American society of bariatric physicians; CDC, centers of disease control; CHD, coronary heart disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HTN, high blood pressure; AKI, acute kidney injury; AVN, avascular necrosis; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; MAT, multifocal atrial tachycardia

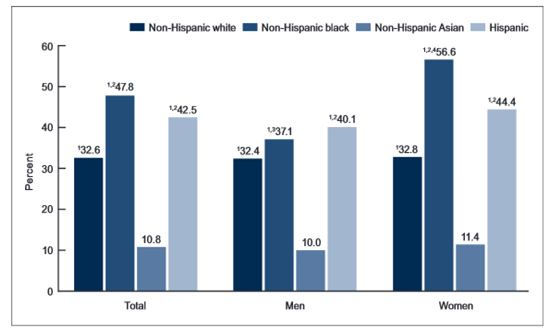

According to the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology and The Obesity Society, Obesity is now recognized as a disease and doctors should more actively treat obese patients for weight loss.1 With more than one-third of U.S. adults being diagnosed as obese in 2011-2012, obesity is the most common medical disease that primary care providers will treat (AMA 2013). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines obesity disease as the condition of excess body fat to the extent that health is impaired. The American Society of Bariatric Physicians (ASBP) also defines obesity as a chronic, relapsing, multifactorial, neurobehavioral disease, where in an increase in body fat promotes adipose tissue dysfunction and abnormal fat mass physical forces, resulting in adverse metabolic, biochemical and psychosocial health consequences. In the past three decades, obesity drastically increased in prevalence in the United Sates and other parts of the Western World. According to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) health disparities and inequalities report of 2011, the prevalence of obesity varies by age, sex, race-ethnic groups, socioeconomic status and geographical region; Obesity increases with age. According to CDC’s 2011-2012 report, the prevalence of obesity was higher among middle aged adults, 40-64years of age, (39.5%); Obesity prevalence was highest among females than males; also the prevalence of obesity was higher among non-Hispanic black (47.8%), Hispanic (42.5%), and non-Hispanic white (32.6%) adults than among non-Hispanic Asian adults (10.8%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Showing Prevalence of Obesity by gender, ethnicity and age (CDC Report, 2011-2012).

1Significant difference from non-Hispanic Asian.

2Significant difference from non-Hispanic White.

3Significant difference from women.

4Significant difference from Hispanic.

Note: Estimates are age-adjusted by the direct method to the 2000 U>S> census population using the age 20-39, 40-59, and 60 and over.

Source: CD/NCHS, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012.

Obesity can result from endocrine medical disorders such as Cushing’s syndrome and hypothyroidism or drug induced brought forth by pharmacological agents that may increase weight gain in individuals. Genetics explains for 40-50% of an individual’s body mass index (BMI) or height for weight. Genetics plays a role in influencing an individual’s taste; appetite; intake; energy expenditure; and energy storage. Also, studies show a correlation with the prevalence of obesity in children with obese parents. For an individual with two obese parents, offspring have an 80% increased risk for also becoming obese and with one obese parent offspring have a 40% increased risk. However, obesity is largely determined by lifestyle and environment factors because even in history, famine has shown to prevent obesity even in the most obesity prone individuals. Environmental factors such an “obesogenic” environment or toxic food environment provides individuals with the convenience of low cost, tasty, high energy dense foods in large portion sizes readily available as seen in the US and the developed world. Compared to 1971 to 2005, American females and males have increased to 200–300kcals per day. Also, refined grains, sugars and added fats are among the cheapest sources of dietary energy, longer shelf life and easier to prepare. Now there are barriers for nutrient dense foods such as commutative high prices for whole grains, fruits and vegetables, lack of convenience and access. Our environment has also evolved to individuals walking less and more driving for transportation, viewing more television, playing video games or using the computer instead of getting the proper physical activity per day. Lastly, new studies have shown gut micro flora could also play a role in influencing the risk for obesity. The individual makeup of good and bad bacteria in the human gut may possibly be affecting the metabolism of foods. Studies have shown some bacteria are more efficient in extracting calories from foods and breaking down fiber then other bacteria in the gut.

Risks and consequences of obesity

Obesity disease greatly increases the risk for development of many other health problems. Obesity increases the risk for coronary heart disease (CHD), high blood pressure and stroke. Obesity increases the risk for developing type two diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance in which the body’s blood glucose, or blood sugar, level is too high and the body’s cells are able to use insulin properly. Metabolic syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, endocrine disorders, sleep apnea, osteoarthritis, cancers and increased risk for mortality are all associated risks for obesity.

A 52year-old African American female (MJ) with a PMH of acute asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), high blood pressure (HTN), acute kidney injury (AKI), avascular necrosis (AVN) of the left hip 2/2 steroid use, awaiting hip replacement, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), h/o depression/bipolar disorder was presented for her pulmonary care clinic as she was found to have multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT), with rapid ventricular rate on electrocardiogram and exacerbation of COPD.

Nutrition assessment

A comprehensive nutrition assessment was conducted for our patient on October 09, 2014; this included anthropometric assessment as reported in Table 1. Other areas of assessment included client history to include past medical history, family history, social history and nutrition focused physical findings to include skin assessment. Other assessment included: diet/food nutrition history of a typical day’s intake, this showed that the cooking method of frying was most employed; additionally, her intake of sodium far exceeded DRI; also her fiber intake was inadequate and she consumed mostly refined carbohydrates. Biochemical assessment was done as reported in Table 2; also medications and physical activity level were reviewed.

Height |

65 in. |

Current weight (10/9/14) |

210.312 lbs. |

Usual Body Weight (6/10/14) |

208.09 lbs. |

%Weight Change |

Notable gain of 1.05% (2.2 lbs./4 months). |

BMI |

34.08, obesity class I |

IBW |

125 lbs. |

IBW Range |

112.5 -137.5 lbs. |

% IBW |

168% |

ABW |

146.32 lbs. |

Table 1 Showing Study Participant’s Anthropometric Data collected on 10/09/2014

Abnormal Lab Value |

Reference Value |

10/9/14 6:20 AM |

10/8/14 7:30 AM |

10/8/14 12:45 AM |

10/7/14 5:21 PM |

Reasons for Abnormality |

Creatine Phosphokinase (CPK) |

10–120 mcg/L |

Data Not Available |

519 H |

674 H |

874 H |

Inflammation of the heart muscle |

Glucose |

70–115 MG/DL |

137 H |

Data Not Available |

105 |

81 |

Glucocorticosteriod use, diet high in carbohydrate, pre-diabetic |

Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) |

7-25 MG/DL |

31 H |

Data Not Available |

21 H |

24 H |

Decreased Kidney/ liver function |

Creatinine Serum |

0.6–1.2 MG/DL |

1.4 H |

Data Not Available |

1.1 H |

1.3 H |

Decreased Kidney/ liver function |

Red Blood Cell |

4.6–6.07 X10E1 |

3.5 L |

Data Not Available |

3.69 L |

3.8 L |

Cigarette smoking, decreased heart function, dehydration, hypoxia |

Hemoglobin |

14.6-17.8 g/dL |

9.6 L |

Data Not Available |

10.1 L |

10.5 L |

Nutrition deficiencies, CKD, malnutrition |

Hematocrit |

40.8-51.9 |

30 L |

Data Not Available |

31.5 L |

32.3 L |

Destruction of RBC, nutrient deficiencies |

Neutrophil % |

38–80% |

85.6 H |

Data Not Available |

89.3 H |

57.4 |

Acute metabolic stress |

Lymphocyte% |

11-49% |

9.8 L |

Data Not Available |

9.1 L |

28.9 |

Acute metabolic stress |

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) African American |

> 90 mls/min/1.73 |

51 L |

Data Not Available |

62 L |

54 L |

Decreased kidney function |

International normalized ratio (NIR) |

1.12-1.46 INR |

1.91 H |

Data Not Available |

1.95 H |

Data Not Available |

Blood thinning med, low levels of blood clotting factors |

Prothrombin Time |

12.5–14.5 sec |

21.9 HH |

Data Not Available |

22.2 HH |

Data Not Available |

Blood thinning med, low levels of blood clotting factors |

Table 2 Showing Study Participant’s Biochemical Data

The study participant reported a limited physical activity level secondary to avascular necrosis (AVN) of the left hip 2/2 steroid use; she was awaiting hip replacement surgery. Based on her height, weight, age, and sedentary physical activity level, her total estimated energy requirement was 1,880-2,040Kcal/day, per the Mifflin-St Je or equation and stress factor of 1.2-1.3.

Nutrition diagnosis

Proceeding from the Nutrition Assessment 6 nutritional problems were identified; however, 2 were selected as priority. Consequently, using the nutrition diagnostic labels (included in parentheses), the following Nutrition Diagnostic Statements (PES) were developed:

PES #1: Obesity, class I and Excessive energy intake (NC-3.3) (NI-1.5) RT portion control, lack of physical activity, and food-nutrition related knowledge deficit AEB registered nurse (RN) report of patient requesting double portions with meals, BMI 34.08, and %IBW 168% (obesity).

PES #2: Drug nutrient interaction of glucocorticosteroid use (solu-medrol) (NC-2.3) RT COPD AEB avascular necrosis of left hip, hip replacement surgery and, elevated blood glucose of 137mg/dL.

Nutrition intervention

Prior to application of nutrition intervention M.J’s existing barriers to the interventions were identified and addressed. Barriers to the intervention were identified as: her inability to prepare her own meals as she was assisted by Home Health Aide/Nurse and her mother; her exercise capacity as she was pending Hip replacement surgery; Comorbidities: COPD/asthma, AKI, HTN, AVN and GERD; economic status (unemployed) and food security; as well as her stage of change: Pre-contemplation. Consequently, the motivational interviewing technique was employed as well as application of Strategies for Stages of Change: Pre-Contemplation. This included: raised M.J’s awareness of healthy and unhealthy eating behaviors; discussed concern for health & psychosocial effects of obesity; explored the advantages of changing; assessed M.J’s level of readiness to change, self–efficacy and, level of confidence in changing with a rating scale questionnaire; identified barriers to change and possible solutions. This was done to facilitate patient goal setting to achieve areas that M.J was willing and ready to make change towards (action stage). Additionally, printed educational material imparting information about ways to effectively utilize available resources was left for M.J’s mother and home health aides; as their efforts can help to reduce the health disparities of obesity. This included a sample one-day menu as seen in Table 3; using foods similar to that reported on her Typical Day’s Intake. This menu meets her macronutrient needs; provides adequate fiber; Vitamin D; and does not exceed her sodium needs.

Meal |

Food Item |

Total Kcals |

Breakfast |

1 cup Oatmeal |

392 kcals |

1 cup 1% milk |

||

1 Banana |

||

8 oz. 100% Orange juice with calcium and vitamin D |

||

AM Snack |

1 small apple |

284 kcals |

2 tbsp. peanut butter (reduced sodium) |

||

Lunch |

3 oz. Baked chicken breast |

369 kcals |

¾ cup Cooked collard greens |

||

½ cup Cooked carrots |

||

1 Whole wheat biscuit |

||

8 oz. 1% Milk |

||

Afternoon Snack |

1 cup low fat yogurt |

231 kcals |

½ cup grapes |

||

8 oz. water |

||

Dinner |

3 oz. Baked fish fillet |

590 kcals |

Mashed sweet potatoes |

Total: 1,974 kcal |

|

1 T. margarine |

||

1 cup steamed broccoli |

||

1 whole wheat dinner roll |

||

8 oz. water |

Table 3 Showing Sample One Day Menu for Study Participant

Patient centered goals and interventions were established for the two priority nutrition problems based on the PES statements. Therefore, to address the nutrition diagnosis of Obesity, class I and Excessive energy intake (PES#1) the following goals were identified: To reduce daily caloric intake by 500 kcal/day to promote 1-2lbs. wt. loss/week; To promote 2-4lbs. weight loss/month until goal weight of 10% actual body weight; 20lbs. weight loss in ~180days is achieved; and to decrease future risks of: Asthma/COPD exacerbation; sleep apnea and CVD through weight loss. Subsequently to achieve these patient centered goals identified the following nutrition interventions were done: Recommended Food & Nutrient Delivery of 1800-2000 kcal/day; Provided Nutrition Education on: portion awareness/control; a general healthful diet–TLC diet; meal planning; Printed material provided; Provided Nutrition Counseling to facilitate lifestyle changes using the Cognitive Behavior Theory to help pt. better understand the factors that influence her behaviors.

Additionally, to address the nutrition diagnosis of Drug nutrient interaction of glucocorticosteroid use (PES#2) the patient centered goal identified was to maintain bone health with coordination of care and prevent further complications and risks of osteonecrosis/osteoporosis. Consequently to achieve this goal the following nutrition interventions were done to increase M.J’s intake of Vitamin D: Encouraged increase consumption of calcium and vitamin D rich foods; Diet Supplement: 1200-1500mg/day of calcium (*if needs not met via diet) and recommended 400IU of vitamin D; Recommended continued coordinated care with physical therapy to increase mobility; Recommended collaborated care with occupational therapy for weight bearing physical activity for upper body strength.

Nutrition monitoring and evaluation

Considering that M.J was seen in the clinical setting at a hospital, monitoring was not as comprehensive as it would have been if it included a post-interventional assessment. Nonetheless, the following indicators and criteria for monitoring M. J’s lifestyle interventions were identified:

Criteria: Gradual weight loss of ~ 2-4lbs./month

Criteria: 24hour food recall with compliance to dietary recommendations of general healthful diet (TLC diet), 2 gm Na and increased vitamin D.D and Ca recommendations

Criteria: Values to reference range: hydration, skin integrity, electrolytes, complete blood count, GFR, lipid panel, urinalysis

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Health Disparities and Inequalities Report (2011) the health disparities in the USA include: race/ethnicity; gender; age; socioeconomic status and geographic regions. Prevalence highest amongst the following: African Americans and Mexican Americans; females; low-income households; amongst the WHO Regions of the Americas increases; also prevalence increases with age>20 (CDC, 2011).The patient profile of this study participant showed a high correlation with the associated health disparities of obesity: 52 Y/O African American Female with a low socioeconomic status.

Additionally, this study showed that the patient’s daily caloric intake greatly exceeded daily recommended needs and caloric expenditure due to limited physical activity level and intake of double portions at one sitting. Study investigations showed existing barriers to intervention as food security; and food and nutrition knowledge deficit on ways to effectively utilize available resources that can help to reduce the health disparities of obesity. Consequently, this study made recommendations for lifestyle modification through portion control awareness; TLC Diet to include increased fiber intake at meals to increase satiety level and limit patient request for double portions. Supporting studies with rats suggest caloric deficit produced by food restriction proportionately declines resting metabolic rate.2 Similar studies by Arrebola3 and Meckling4 reported that lifestyle modification of a low calorie diet in combination with exercise in severely obese patients may successfully reduce body weight and body fat.

This study was significant for the dietetic and nutrition practice because it explored the health disparities of obesity rather than only anthropometric measurements. One major implication of this study was that the patient and caregiver (mother) considered the nutrition education and counselling sessions (to include application of the stages of change theory) very helpful, informative and worth their time. The sessions facilitated patient goal setting and patient verbalized understanding of the need to make diet and lifestyle changes to minimize the risks of obesity.

Nonetheless, there were limitations to this current study. They included: the small, non-probability sample size; as well as the convenience of using a clinical setting in close proximity to researchers due to financial constraints; these factors limit the generalizability of the study. Another limitation was that nutrition support follow up assessment with longer follow-up intervals at 4, 8 and 12 weeks would uncover more or less favorable results over time.5‒13

In spite of the fact that the nutritional interventions of: reduced caloric intake of 500-1000kcal/daily through portion control awareness; limited refined CHO and increased fiber intake; and recommendations for therapeutic lifestyle change did not show statistical significance in this study, the clinical and nutritional implications warrant further investigation.

None.

Author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

©2016 Smith-Hawley, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.